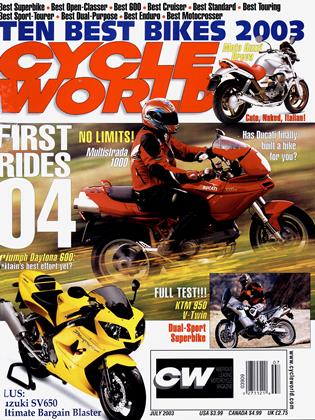

DUCATI MULTISTRADA

All roads lead to Roam

MARK HOYER

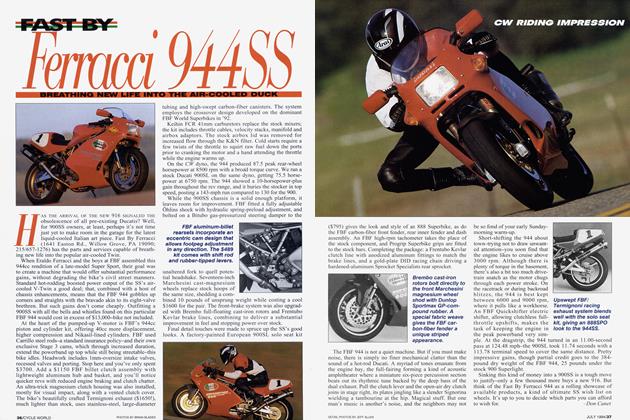

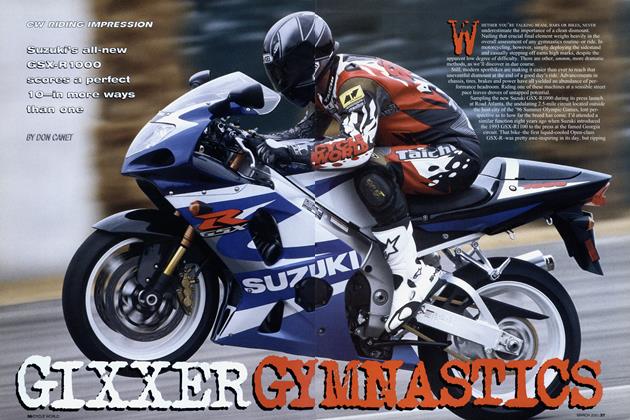

CW RIDING IMPRESSION

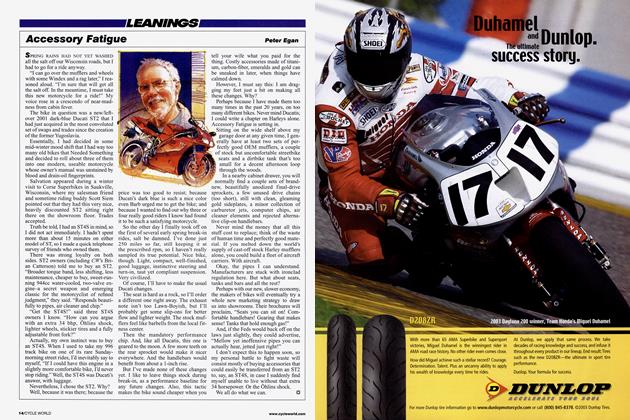

IT WAS HARD NOT TO FEEL SORRY FOR THE OLD SHEPHERD TENDING HIS FLOCK near the winding road on the south coast of Sardinia, a large Italian island in the Mediterranean Sea. He was just minding the herd, as he's probably done for the past 50 years or so, smoking a mangled, hand-rolled cigarette and holding his wooden staff, surveying the rolling hills and lush greenery that his beasts wandered through and fed upon.

One suspects it is usually a quiet place. Today was different. There was a mad herd of red Ducati Multistradas in a steel stampede, all suffering from a severe case of Mad Journalist’s Disease, a degenerative brain disorder brought about by being passed by a peer.

Sardinia, or “home” as the locals call it, is this wonderfully isolated-feeling place, a mere one-hour flight from Rome, but it feels like 50 years ago and thousands of miles away. Think of it as the Land that Time Vaguely Remembers. There are few people, particularly because it’s a summer resort retreat, and we were there during spring. So it was mostly cool sunny days, no traffic, and some of the best roads I’ve ever ridden in my life. Plus, in the lagoon across the road from the hotel, there were even non-fiberglass pink flamingoes walking on water as they took to the air. Magic.

I wish I’d taken the time to see more of the place, but when you’ve got your rosso Multistrada heeled over on its footpegs in every comer, and are zinging the torquey twovalver out to eight thou on every exit, you tend to focus only on the asphalt ahead. Yes, in this job you get to see the world, and it quite often ends up looking like various shades of gray tarmac.

But this Ducati is red, and it commands attention. The main question about the Multistrada since it broke cover two years ago: What the hell is it? Not your traditional Ducati, certainly, but the Bologna Bunch was pretty adamant in stating, “It is not a dirtbike,” even though it echoes the giant adventure-touring trailie niche typified by the BMW RI 150GS.

So what was the prime directive behind the bike? Build the perfect Ducati for the Futa. Of course! The whata?!

The Futa Pass is a mountain road (medium-gray asphalt, good quality to poor...) leading from Ducati’s home in Bologna to Florence, over the Apennine Mountains. Speed limits generally are not enforced, and conditions vary widely. This latter point is the point: The Multistrada is meant to be a bike for all streets (multiple stradas), good or bad. So it wears 17-inch wheels front and rear, as befits a modem streetbike. But because modem streets are also bumpy, suspension travel front and rear is longer than on other Ducatis, and the Pirelli Scorpion Sync tires wear big, aggressive-looking tread blocks. The riding position is upright but sporty, the handlebar wide and tubular, with a protective half-fairing. Engine tuning emphasizes immediate available torque.

It is meant to be a bike for all occasions, and the making of such was not an easy task, according to Ducati’s design chief, Pierre Terblanche, on hand for the Strada’s introduction.

“Building a perfect all-rounder is even more focused than building a bike to do one thing very well,” he says.

Plus, the company is well aware of the fact that its bestselling model is a design now more than 10 years old.

“We need the next Monster,” Terblanche says of the bike that accounts for some 50 percent of Ducati sales. “To sit down and actually think of what the next niche success might be is very difficult. Three years ago, we had no idea if the Multistrada concept was the right one. But the way the market has evolved, we think it is.”

The concept may have been difficult, but at least with Ducati you know core parts are going to be pretty easy to select: V-Twin and a steel-trellis frame.

So, the frame started as an ST2 sporttourer’s, but with alterations to make it more suitable for its new mission. Because the Strada is likely to see more demanding (read: rougher) roads than other Ducks, the steering-head tube is longer and therefore more rigid, and the single-sided swingarm (chosen because it looks cool and makes changing the rear tire easier) has its pivot traveling through both the engine and the lower cast frame plates/forged footpeg mounts. The triple-clamps were offset farther and the frame swept back more aggressively from the head tube to give the bike more steering lock than Ducatis traditionally have.

It’s a simple thing, but pretty damn impressive. After 10 years in this business doing U-tums for the

camera, you know that with Ducatis you’re always very cautious turning around. With the Multi, you just turn impossibly tight, like you’re burying a dirtbike in a berm. Good stuff. Please apply to all other models.

The engine, meanwhile, is Ducati’s excellent new 992cc Dual Spark air-cooler. We were impressed with it in the Supersport 1000, and dug it in the new Monster, but thanks to the Strada’s shorter gearing (plus four teeth at the rear over the SS) and different airbox and exhaust, it feels livelier than ever. It also feels smoother. Maybe this can be credited to the damping effect of the giant plastic fuel pellet upon which you sit, or perhaps the shorter gearing? Whatever the case, this is one smooth Desmo.

Plastic fuel pellet? It’s quite the technical achievement, actually. Because the 10.5-liter airbox has to go somewhere-where the fuel normally would like to reside-the gas has to go somewhere else. In this case under the seat and practically into the tailsection. It is a roto-molded piece with internal structure (remember, you sit on it), made by Acerbis. To be sure that the full 5.3-gallon capacity can be utilized, it was necessary to make a couple of interesting technical solutions: There is an air-relief valve at the rear, so that when you fill the tank, the air that would normally escape out the filler neck (in the usual location) but can’t because it is trapped under the passenger seat, now vents through the valve. It also provides a seal against fuel escaping, of course, but just to be sure, there’s a small subtank that drains back to the main after the fuel level drops. The main tank is anchored at the front with screws; to compensate for heat expansion, the rear mounts are pins and adjustable pads, on which the tank can slide-the vessel can grow as much as 5mm from cold to hot. All this, just to carry the fuel.

That’s the challenge of trying to “build a lOOOcc bike that is the same size as a 650,” says Terblanche. “We have 10.5 liters of airbox capacity, 10 liters of exhaust capacity, 20 liters of fuel, in a narrow package with a 90-degree V-Twin engine. It really isn’t very easy.”

Putting the fiiel under the rider also allowed the tank to be narrow, although long-femured riders find their knees hitting the tank as it grows wider toward the front. Overall, though, this is a very comfortable motorcycle. Moving around for mild hanging off was very easy and natural feeling. Bar and footpeg placement is excellent, and the only item for complaint is how hard the seat is. True, you get good information from the bike because the pad is so firm and broad, but your ass is going to be the first thing to cry mercy on a long ride. Even the optional touring seat fitted to one of the bikes on hand was a rock. It was thicker, but still stone-like.

Despite its unconventional looks, out on the asphalt the Multistrada is your basic Ducati sportbike. It feels very light and quite small. Available lean angle is impressive, and only at a ridiculous street pace do the footpegs, then other parts, drag. On the right, the exhaust heat shield and brake pedal touched down, with the bad effect of lifting the front tire off the pavement momentarily. Even with this recklessness, though, the ride was still wreckless.

Nice suspension adjustability, too. Our testbike’s Showa shock was set up with minimum compression and spring preload for a plush, comfortable ride, but was still acceptably stable when pushed hard. It was, however, raining the first morning we rode the bike. In the afternoon, we were greeted by dry pavement with lots of grip. Bumping preload with the handy hand-operated remote adjuster was simple as can be, and tightening up both compression and rebound asserted better control over the rear end. The inverted Showa fork’s long travel (6.5 inches) was appreciated, especially when slamming down after botched wheelies, though there was some harshness on medium-sized bumps. You could adjust this away for the most part, but only at the expense of some control. Pick your tradeoff.

While the Multistrada is capable of ripping along at a very high rate of speed, and is quite entertaining in this kind of use, it is when you back the pace down a bit that you realize how easy this bike is to ride. Stability is excellent in a straight line and also mid-comer. Because of the riding position and tall, wide handlebar, cornering transitions are very loweffort-a succession of esses is dreamland on the Multi.

The wide bars help this, but also the fact that the front wheel is lighter and more rigid than the one fitted to the 999. Tme! The 320mm semi-floating Brembo discs are mounted directly to the hub with floating pins, similar to what BMW has done on many of its bikes in recent years. This is lighter and stiffer than using the normal, intermediate brake carrier. In fact, this wheel was originally designed for the 999, but was determined not to fit that bike visually. The brakes are quite strong, as we’ve come to expect from Gold Brembos. Only under very hard trailbraking does the bike exhibit a minimal tendency to stand up or deviate from your chosen cornering line.

Terblanche said that the inspiration for getting the airflow around the

fairing right came from getting it wrong on his own previous design, the Cagiva Gran Canyon.

‘T went for a long ride on my Cagiva and the buffeting was so bad I was mad at myself!” he says. “So I wanted a bike comfortable enough that you wouldn’t want to beat up the designer after a long ride.”

Mission accomplished, and thank goodness, because Pierre is a pretty big guy, and I’m not sure I could take him. Anyway, it wasn’t an issue, because air management is very good for a bike with what is really quite a small fairing. Flow is smoooooooth at helmet level, even at high speeds (we saw 120 mph). It is big enough to tuck in behind, although the screen’s optical quality leaves a little to be desired. The top half of the fairing is anchored to the bars so that it moves with them, thus helping to facilitate the excellent steering lock. A very simple, excellent solution that also allows great freedom in bar placement.

Accessories abound for the Multistrada, from fullboat sporty stuff such as lighter-weight slipper clutches (the slipper part is standard), carbon-fiber wheels and magnesium engine sidecovers, to touring niceties such as heated grips, handguards and rubber-coated footpegs.

Even a GPS system is available, although to fit this unit, it’s necessary to remount the gauges higher (pieces included), which in turn necessitates the use of a taller, optional windscreen.

The $11,800 Multistrada definitely lands on the streetoriented side of the adventure-touring realm. It’s probably as dirt-worthy as a Suzuki V-Strom or Triumph Tiger, maybe even more so because of its much lighter weight, but loses the vestigial big dirtbike-ish front wheel. So, if the new KTM 950 Adventure (see test, page 60) is the dirty bookend, this here is the sportystreet bookend, with the BMW RI 150GS the natural center of the class.

But underneath all this adventure-touring hubbub is really just another fast and fun Ducati sportbike, one that’s much easier to live with than any to come before. See you out on the road-which one is your choice.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue