TRIUMPH TROPHY 1200

CW RIDING IMPRESSION

THE BRITS GO FOR PHASE TWO

ALAN CATHCART

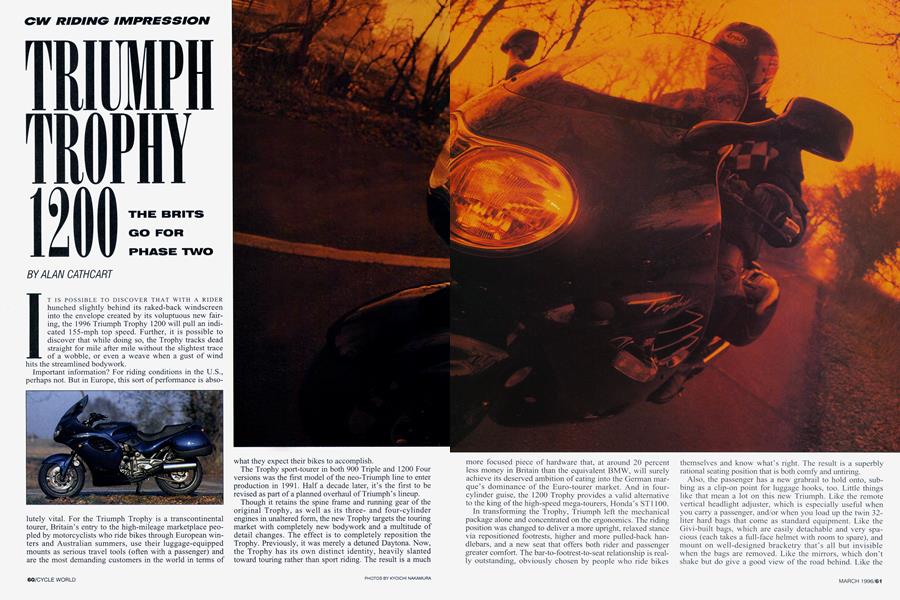

IT IS POSSIBLE TO DISCOVER THAT WITH A RIDER hunched slightly behind its raked-back windscreen into the envelope created by its voluptuous new fairing, the 1996 Triumph Trophy 1200 will pull an indicated 155-mph top speed. Further, it is possible to discover that while doing so, the Trophy tracks dead straight for mile after mile without the slightest trace of a wobble, or even a weave when a gust of wind hits the streamlined bodywork.

Important information? For riding conditions in the U.S., perhaps not. But in Europe, this sort of performance is abso-

lutely vital. For the Triumph Trophy is a transcontinental tourer, Britain’s entry to the high-mileage marketplace peopled by motorcyclists who ride bikes through European winters and Australian summers, use their luggage-equipped mounts as serious travel tools (often with a passenger) and are the most demanding customers in the world in terms of what they expect their bikes to accomplish.

The Trophy sport-tourer in both 900 Triple and 1200 Four versions was the first model of the neo-Triumph line to enter production in 1991. Half a decade later, it’s the first to be revised as part of a planned overhaul of Triumph’s lineup.

Though it retains the spine frame and running gear of the original Trophy, as well as its threeand four-cylinder engines in unaltered form, the new Trophy targets the touring market with completely new bodywork and a multitude of detail changes. The effect is to completely reposition the Trophy. Previously, it was merely a detuned Daytona. Now, the Trophy has its own distinct identity, heavily slanted toward touring rather than riding. The result is a much more focused piece of hardware that, at around 20 percent less money in Britain than the equivalent BMW, will surely achieve its deserved ambition of eating into the German marque’s dominance of the Euro-tourer market. And in fourcylinder guise, the 1200 Trophy provides a valid alternative to the king of the high-speed mega-tourers, Honda’s STI 100.

In transforming the Trophy, Triumph left the mechanical package alone and concentrated on the ergonomics. The riding position was changed to deliver a more upright, relaxed stance via repositioned footrests, higher and more pulled-back handlebars, and a new seat that offers both rider and passenger greater comfort. The bar-to-footrest-to-seat relationship is really outstanding, obviously chosen by people who ride bikes

themselves and know what’s right. The result is a superbly rational seating position that is both comfy and untiring.

Also, the passenger has a new grabrail to hold onto, subbing as a clip-on point for luggage hooks, too. Little things like that mean a lot on this new Triumph. Like the remote vertical headlight adjuster, which is especially useful when you carry a passenger, and/or when you load up the twin 32liter hard bags that come as standard equipment. Like the Givi-built bags, which are easily detachable and very spacious (each takes a full-face helmet with room to spare), and mount on well-designed bracketry that’s all but invisible when the bags are removed. Like the mirrors, which don’t shake but do give a good view of the road behind. Like the new headlamps with their chrome bezels, which not only give a strong sense of identity to the Trophy’s face, but also give really good illumination on high-beam for rapid night riding.

The 1200’s counterbalanced engine has exactly the same seamless state of tune as before, delivering a claimed 106 horsepower at 9000 rpm. That’s matched by maximum torque of 77 foot-pounds at 5000 rpm. This makes for an effortless, easy pull from as low as 1000 rpm up to the red zone at nine grand, and above. The engine is so eager to please that you can cruise through city streets in top gear, paying attention to the speed limits, then just flick your wrist

on the other side of town and switch back into maxi-mode for the open highway-all without changing gear once. It’s the nearest thing to an automatic gearbox on two wheels.

Even in top gear, the midrange roll-on between 70 and 100 mph is truly awesome. Cruising in fifth behind a line of cars hogging the fast lane on a freeway invites you to power instantly into the space left available when one of them obligingly pulls over. Easy, with the Trophy. So is speeding between turns on an open country road, or through twistier stuff, where the Trophy engine’s impressive response makes short work of zapping past traffic in short, fast squirts. This is the two-wheeled equivalent of a Jaguar XJR, offering passenger space and luggage capacity combined with a silky smooth engine, muscular pickup and powerful performance, at some cost in terms of fuel economy-though 34 mpg overall, mixing freeway blasts with hilly hikes, isn’t that bad for a 1200cc Four.

But don’t think the Trophy is strictly a point-and-squirt machine, because within the limits of its claimed 518-pound dry weight and undeniable bulk, it does handle-not nimbly, but at least adequately. The bike’s 58.7-inch wheelbase and 27-degree fork angle deliver fine stability through long sweeping turns, and thanks to the good handlebar leverage, there’s no undue effort spent cranking it around tight hillside turns or city comers.

The 43mm Kayaba fork with its dual-rate springs delivers good ride quality and adequate suspension response for a touring bike, but the shock, also by Kayaba, is less capable. Kayaba moved the compression damping knob to the bottom

of the alloy-bodied shock, which is okay, but it’s also eliminated the remote preload adjustment altogether, which isn’t. Altering the preload setting is now a job entailing a visit to your nearest Triumph dealer, the rationale apparently being that before a Trophy owner takes off on a trip, he’s going to want to have the bike serviced anyway. Maybe, but not being able to adjust preload any time you feel the need, especially on a sport-touring bike, is just plain silly. Add in the fact that this shock has insufficient rebound damping, and I’d have to say that Triumph needs to rethink its rear suspension package on this bike to make it more suited to touring practicalities.

Here’s another, and equally important, problem: With upwards of 880 pounds to stop when the Trophy is loaded with fuel, passenger and luggage, the twin 12.2-inch Nissin floating front rotors and four-piston calipers require an awfully hard squeeze on the adjustable lever to stop the bike properly. Stomping on the rear brake pedal-which activates an 8.9-inch disc-doesn’t make a big difference, especially as the pedal must travel through quite a long arc before it starts to engage the brake. Until Triumph addresses this glitch, Trophy owners who plan to tour two-up need to flex their way to best braking performance via a strong right hand.

The Trophy’s extensive range of options, which includes a chain enclosure, heated handgrips and a top-box, also lists a taller screen than the one fitted as standard. In my opinion, this latter item should not have to be purchased-because Triumph doesn’t include an adjustable screen with its improved touring package for the Trophy, it should at least allow taller riders the option of choosing a higher screen at no extra cost at the time of purchase. At 5-foot, 11-inches, I found the airflow off the standard screen aimed right at the top of my visor, creating undue noise and turbulence. Slouching down a couple of inches produced a dramatic improvement, at the cost of negating Triumph’s fine work on the upright riding position.

These problems aside, the alterations made to the new Trophy have turned it into a fine motorcycle capable of covering great distances two-up with luggage, at impressive speeds with a high degree of comfort. Add in the exceptional quality of manufacture and thoughtful attention to detail, and it seems obvious that the touring market has a new contender for the title of champion mile-eater. □q

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontFifty-Buck Beezer

March 1996 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsOur Brother's Keeper

March 1996 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTorque Shows

March 1996 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1996 -

Roundup

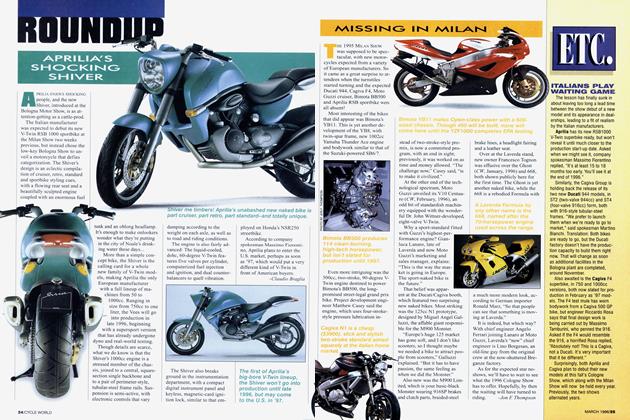

RoundupAprilia's Shocking Shiver

March 1996 By Claudio Braglia -

Roundup

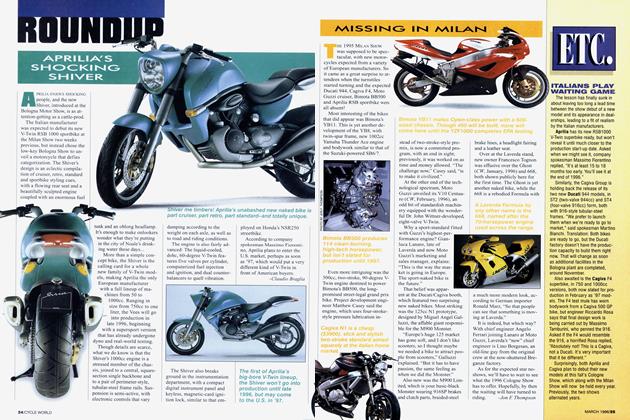

RoundupMissing In Milan

March 1996 By Jon F. Thompson