Clipboard

RACE WATCH

Rossi’s rocky rally debut

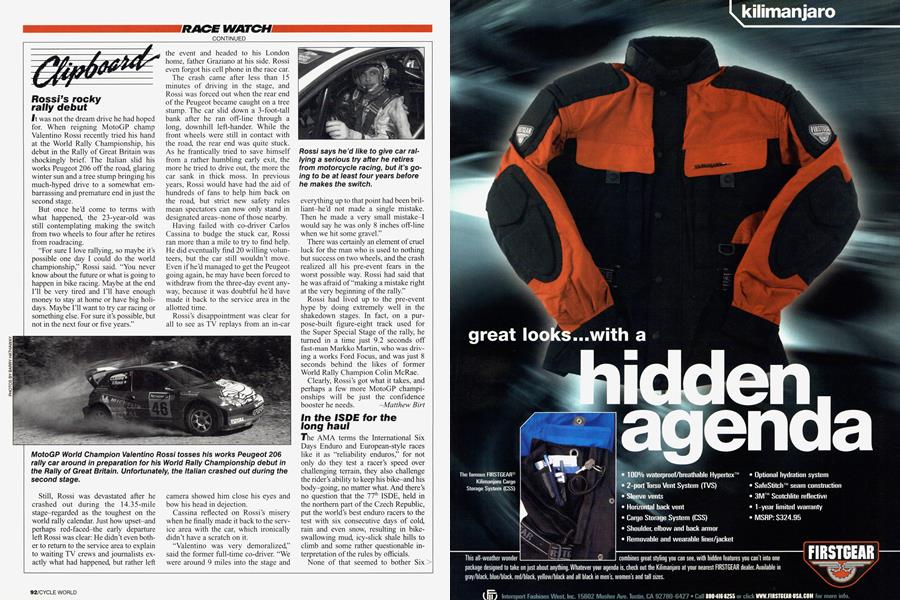

It was not the dream drive he had hoped for. When reigning MotoGP champ Valentino Rossi recently tried his hand at the World Rally Championship, his debut in the Rally of Great Britain was shockingly brief. The Italian slid his works Peugeot 206 off the road, glaring winter sun and a tree stump bringing his much-hyped drive to a somewhat embarrassing and premature end in just the second stage.

But once he’d come to terms with what happened, the 23-year-old was still contemplating making the switch from two wheels to four after he retires from roadracing.

“For sure I love rallying, so maybe it’s possible one day I could do the world championship,” Rossi said. “You never know about the future or what is going to happen in bike racing. Maybe at the end I’ll be very tired and I’ll have enough money to stay at home or have big holidays. Maybe I’ll want to try car racing or something else. For sure it’s possible, but not in the next four or five years.”

Still, Rossi was devastated after he crashed out during the 14.35-mile stage-regarded as the toughest on the world rally calendar. Just how upset-and perhaps red-faced-the early departure left Rossi was clear: He didn’t even bother to return to the service area to explain to waiting TV crews and journalists exactly what had happened, but rather left the event and headed to his London home, father Graziano at his side. Rossi even forgot his cell phone in the race car.

The crash came after less than 15 minutes of driving in the stage, and Rossi was forced out when the rear end of the Peugeot became caught on a tree stump. The car slid down a 3-foot-tall bank after he ran off-line through a long, downhill left-hander. While the front wheels were still in contact with the road, the rear end was quite stuck. As he frantically tried to save himself from a rather humbling early exit, the more he tried to drive out, the more the car sank in thick moss. In previous years, Rossi would have had the aid of hundreds of fans to help him back on the road, but strict new safety rules mean spectators can now only stand in designated areas-none of those nearby.

Having failed with co-driver Carlos Cassina to budge the stuck car, Rossi ran more than a mile to try to find help. He did eventually find 20 willing volunteers, but the car still wouldn’t move. Even if he’d managed to get the Peugeot going again, he may have been forced to withdraw from the three-day event anyway, because it was doubtful he’d have made it back to the service area in the allotted time.

Rossi’s disappointment was clear for all to see as TV replays from an in-car camera showed him close his eyes and bow his head in dejection.

Cassina reflected on Rossi’s misery when he finally made it back to the service area with the car, which ironically didn’t have a scratch on it.

“Valentino was very demoralized,” said the former full-time co-driver. “We were around 9 miles into the stage and everything up to that point had been brilliant—he’d not made a single mistake. Then he made a very small mistake-I would say he was only 8 inches off-line when we hit some gravel.”

There was certainly an element of cruel luck for the man who is used to nothing but success on two wheels, and the crash realized all his pre-event fears in the worst possible way. Rossi had said that he was afraid of “making a mistake right at the very beginning of the rally.”

Rossi had lived up to the pre-event hype by doing extremely well in the shakedown stages. In fact, on a purpose-built figure-eight track used for the Super Special Stage of the rally, he turned in a time just 9.2 seconds off fast-man Markko Martin, who was driving a works Ford Focus, and was just 8 seconds behind the likes of former World Rally Champion Colin McRae.

Clearly, Rossi’s got what it takes, and perhaps a few more MotoGP championships will be just the confidence booster he needs. -Matthew Birt

In the ISDE for the long haul

The AMA terms the International Six Days Enduro and European-style races like it as “reliability enduros,” for not only do they test a racer’s speed over challenging terrain, they also challenge the rider’s ability to keep his bike-and his body-going, no matter what. And there’s no question that the 77th ISDE, held in the northern part of the Czech Republic, put the world’s best enduro racers to the test with six consecutive days of cold, rain and even snow, resulting in bikeswallowing mud, icy-slick shale hills to climb and some rather questionable interpretation of the rules by officials.

None of that seemed to bother Six> Days veteran Jeff Fredette, however. Over the years, he’s probably seen it all when it comes to the world enduro team championship that is considered the Olympics of the sport. He went to his first one in 1978 in West Germany, and earned a gold medal (awarded to those who finish within 10 percent of their class leader’s score) on his Penton. When the most recent ISDE wrapped up, Fredette had an 11th silver medal (for those who are within 40 percent of

their class leader’s score) to add to the 10 golds and a solitary bronze (for finishers) he’s earned in his lengthy and decorated career.

But even more impressive than the fact that he’s earned 22 medals is the fact that he’s finished every Six Days he’s started. Though no one at the FIM has kept track of that sort of stat, Fredette’s staggering accomplishment is widely viewed as a record and the sort of benchmark that epitomizes what enduros are all about.

No longer driven to mix it up with the leaders, Fredette, now in his mid-40s, has a more relaxed attitude about the ISDE, and this in itself will no doubt help him push his record even farther.

“This is the ultimate trail ride-once a year in a different country,” he says. “Now it’s one of those things where you go to do it because it’s there, and it’s an adventure. It’s like an extreme adventuretype thing. It’s the ultimate vacation.”

On the other hand, the rest of Team USA didn’t see the Czech ISDE as a vacation. Of the 41 Americans who started (60 percent of whom were rookies, according to the AMA), just 22 finished, with Fred Hoess-a 13-time ISDE veteran-earning the solitary U.S. gold medal

(his 10th, by the way, to go with a pair of silvers and a DNF from his ’84 ISDE debut). Hoess was one of the three U.S. Trophy team members to finish out of six starters. The team placed a disappointing 16th overall out of 20 countries. The Finnish team took the coveted World Trophy over the Swedes and French.

But perhaps the influx of first-timers signals a new wave of U.S. ISDE hope> fuis, including those who are both speedy and serious enough to prove that Americans are in it not only for the long haul, but are capable of gunning for the lead.

-Mark Kariya

Money for nothing

Without big-money sponsorships and lucrative factory contracts, amateur roadracers have to find their own motivation to ride fast. For Keith Reed, that’s not a difficult thing to do, especially around the middle of each month. That’s when this 39-year-old software engineer and Pittsburgh-area club roadracer faces his most important finish line of all.

“I have to make it home in time to intercept the Visa bills before my wife sees them,” jokes Reed, who in just his third year chasing checkered flags is among the top runners in the Western Eastern Roadracing Association’s Northeast Region. Riding a Suzuki GSX-R600 and 750 in a dozen regional races during the 2002 season, Reed epitomized the savvy, make-do-with-whatyou-have improvisation so prevalent in amateur roadracing.

There is limited glory, great expense and plenty of hardship and risk. For

most, it is the thrill of competition that drives them. Certainly there are cheaper ways to get track time, and a casual track-day rider would have a hard time chalking up the huge season-end bill that Reed did this past season.

Money isn’t the only cost, either. Although many would describe club racers as “weekend warriors,” it’s a title Reed resents. His suburban garage, home of his aptly named Empty Pockets Racing team, remains a beehive of activity for most of the week. After the commute home from his day job, Reed spends most evenings working on his racebikes and planning trips for upcoming rounds.

“It’s never easy, but I know this is what makes him happy,” says his wife Susan, a 36-year-old registered nurse. “Besides, it’s kept him out of bars and out of trouble.”

It was staying out of trouble, Reed says, that drove him to roadracing in the first place. A serious speed freak since riding his first dirtbike at the age of 7, Reed was, by 36, an experienced street rider who was taking a lot of risks.

“I was riding way too fast on the street, and after a day of cop chases and almost wrecking five times, I realized I

had to either get on a track or die. It was that simple,” he says in a mantra oft-repeated by roadracers.

It was, however, a different mortality check that finally got him on the track.

A routine visit to the family doctor revealed a pre-cancerous mole on his back, and Reed realized his time to explore racing wouldn’t last forever.

Surgery successfully removed the melanoma, and Reed wasted about 5 seconds before trying skydiving, then motorcycle roadracing.

Years of stoplight racing and a vein of natural ability translated into the Northeast Region B Superstock Novice championship in 2001, with 14 podium finishes out of 26 entries.

As Empty Pockets Racing started to collect trophies, the bills started to pile up, giving credence to the team name. Manufacturers do offer club racers contingency money for top placings, but it’s seldom enough to cover expenses.

Despite the perpetual cash outflow and the long days on the road, by July of last year, Reed was fifth in WERA’s B Superstock Expert class-an almost unheard-of feat for a late-30s newcomer. But racing at or beyond the limit has its inevitable dangers, and Reed came away mid-season with a shattered collarbone due to a crash.

A few months later, busted shoulder and all, Reed managed to make it to Road Atlanta for WERA’s Grand National Finals in October, finishing mid-pack in several races. It wasn’t the big finale he’d hoped for when the season started, but he was clearly pleased to be back in competition. At an age when most professional roadracers are ready to hang up the leathers for good, Reed is looking forward to at least five more years on the club scene with the Holy Grail of someday competing in an AMA National.

As long as his bones and his Visa cards hold out, Reed thinks he has a pretty fair chance of making it happen.

“What people need to know is if they’re really going to try and do this, it will take every penny they have and all the effort they can give,” he says. “But the rewards are far, far better than I could have ever imagined.” -Mike Seate

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontBike of the Year, 2002

February 2003 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThem Ice Cold Blues

February 2003 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCSpring Fever

February 2003 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

February 2003 -

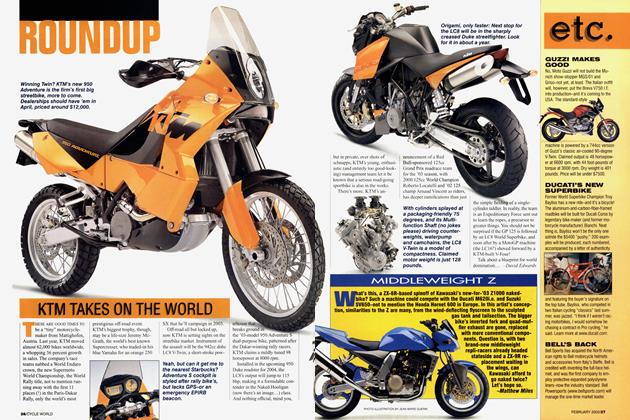

Roundup

RoundupKtm Takes On the World

February 2003 By David Edwards -

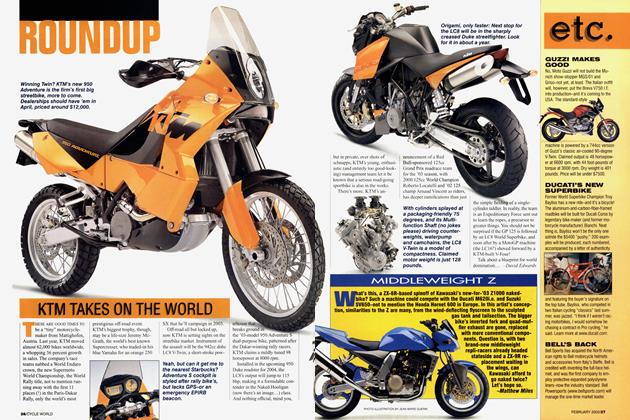

Roundup

RoundupMiddleweight Z

February 2003 By Matthew Miles