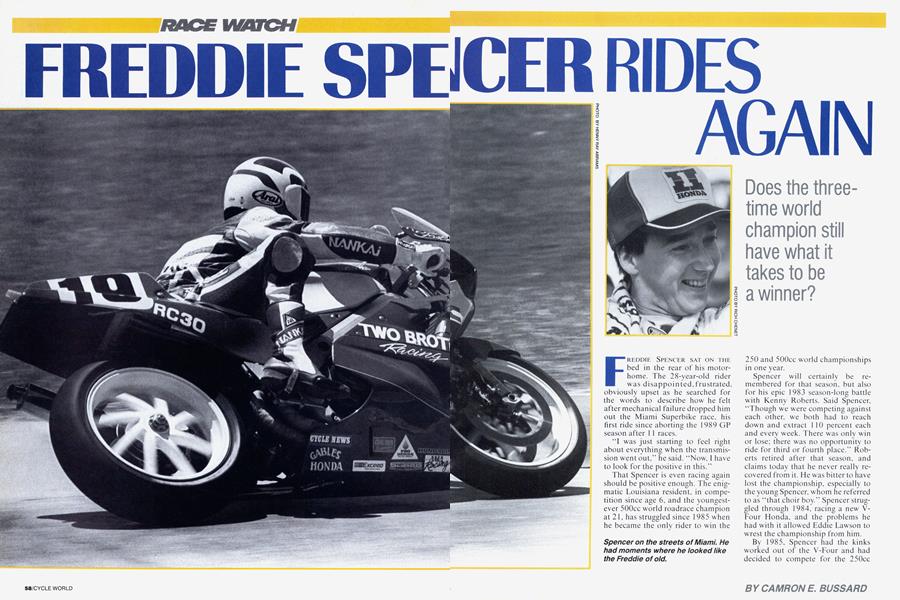

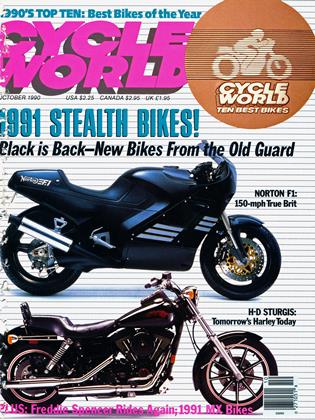

FREDDIE SPENCER RIDES AGAIN

RACE WATCH

Does the three-time world champion still have what it takes to be a winner?

CAMRON E. BUSSARD

FREDDIE SPENCER SAT ON THE bed in the rear of his motor-home. The 28-year-old rider was disappointed,frustrated, obviously upset as he searched for the words to describe how he felt after mechanical failure dropped him out the Miami Superbike race, his first ride since aborting the 1989 GP season after 11 races.

“I was just starting to feel right about everything when the transmission went out,” he said. “Now, I have to look for the positive in this.”

That Spencer is even racing again should be positive enough. The enigmatic Louisiana resident, in competition since age 6, and the youngestever 500cc world roadrace champion at 21, has struggled since 1985 when he became the only rider to win the 250 and 500cc world championships in one year.

Spencer will certainly be remembered for that season, but also for his epic 1983 season-long battle with Kenny Roberts. Said Spencer, “Though we were competing against each other, we both had to reach down and extract 1 10 percent each and every week. There was only win or lose; there was no opportunity to ride for third or fourth place.” Roberts retired after that season, and claims today that he never really recovered from it. He was bitter to have lost the championship, especially to the young Spencer, whom he referred to as “that choir boy.” Spencer struggled through 1984, racing a new VFour Honda, and the problems he had with it allowed Eddie Lawson to wrest the championship from him.

By 1985, Spencer had the kinks worked out of the V-Four and had decided to compete for the 250cc world championship, as well as the 500. For that, he would get credit for jump-starting the Japanese factories’ involvement in the 250 class: Before Spencer and his factory NSR250 dominated the class, privateer bikes could be competitive. Yet even in the midst of his 250 championship battle, some of the 500 riders were accusing him of sandbagging in the class. “Before the season, who believed I could win both classes? I believed, and so did my tuner, Erv Kanemoto, and my mom. But you can get moms to believe anything. That was it,” he says.

It was a strenuous task competing in both classes, and it’s ironic that the record-setting season may have been the cause of Spencer’s subsequent difficulties. “1983 was tough because of Roberts,” says Spencer, “but in '85, it took a different kind of intensity, because I was competing against two people, (former 250 champ) Anton Mang and Eddie Lawson. It took a tremendous amount out of me. I was getting ready for two races a day. I would come in from practice on the 250 then have to jump right on the 500.”

Indeed, winning both championships took a severe toll on Spencer. He had raced so hard that the aggressive riding style he employed to control the violent power of his 500 Honda had aggravated the tendons in his wrists to the point that he required an operation to relieve the pressure.

“After the surgery, I thought I could come right back and be competitive,” he says. “But it took me a while before I realized I was worn down physically and mentally. Those two seasons certainly had an everlasting effect on me.”

After a frustrating year in 1986, > followed by another in 1987, Spencer retired in the spring of 1988, twoand-a-half years after his last championship and in the midst of gossip that insisted Spencer hated to race, that he didn't want to test bikes or tires, that he was a prima donna miffed with his 1987 teammate Wayne Gardner, who had received equal equipment. He says, ‘T tried not to pay any attention to those rumors. They didn’t do the sport any good, nor would it have done me any good to respond.”

Spencer soon found out he didn’t enjoy life without racing, so by year’s end, had signed on to race for Giacomo Agostini’s Marlboro/Yamaha team in 1989. Arch-rival Eddie Lawson had inked a deal with Spencer’s former team, Rothmans Honda, and was using Erv Kanemoto as his tuner. Spencer, on an unfamiliar team and without his trusted tuner, started out by missing a couple of important pre-season test sessions, with no explanation, and as a result, the team never had a chance to get its bikes sorted out. After that, it didn’t take long for Spencer and Agostini to realize their goals for the season were markedly different. ‘T wanted a two year program where I would get back up to speed and develop the bike the first year, then go after the championship the second year. But Agostini needed wins and a championship right away,” he says.

Spencer was not able to deliver that, and the season quickly began slipping away. Once again, the rumor mills were working overtime, with bi-> zarre tales of Spencer secluding himself in his motorhome, refusing to train, preferring instead to watch Elvis Presley videos, and keeping his clocks constantly set to Shreveport time. “I did have one clock on Shreveport time,” he explains, “because I could never figure out the time differences. But I don't even own any Elvis videos.” The season ended with Spencer failing to race after the French GP.

So when the rumors began that Spencer was going to race the Miami AMA Superbike event, most people refused to believe it, even though his early entry helped to convince CBS Sports to televise the event. Held on a street course in downtown Miami, the event was the first of its kind for the AMA. It would be a difficult test for the racers, who would get only> three, 20-minute practice sessions before the late-afternoon race. Spencer, who had leased a Honda RC30 Superbike from Two Brothers Racing in California, hadn't ridden a racebike in nearly 1 1 months. A week before the race, Spencer fueled clucking among the he-won't-show contingent by canceling a crucial test session at Willow Springs Raceway. “Freddie’s been riding an RC30 on the street, so I didn't think we would learn much about the racebike that would do us any good for Miami,” explained Lonnie Hardy, Spencer’s manager. Ralph Sanchez, the promoter of the event, remained optimistic: “You have to believe in people. Freddie agreed to show up, and I have no reason to believe he won’t.”

Speculation on why Spencer chose to race again centered around the possibility of an assault of a world Superbike championship title in 1991. Other rumors claimed that Spencer needed the money, as he was financially ruined and had resorted to selling insurance back in Shreveport. About the racing Spencer says,

“I don’t have any concrete plans to do World Superbike, but at least that organization is doing things right.” He winces when asked about being a impoverished insurance salesman> who will race only if the paycheck is big enough. “I guess the higher you climb, the more people want to tear you down. I’m not broke and there’s not enough money in the Miami race to get me there for the money. I’ve always been interested in the financial side of motorcycling, so I am working in a friend’s insurance company to learn more about finance in general. But I don’t have to do it.”

Then he stopped for a second and sorted his thoughts. “I'll tell you why I’m going to Miami. I liked the idea, the possibilities. Something has to happen to make motorcycle racing more appealing and more accessible. Because of the television coverage, this race has the potential to do that. If it doesn’t work, that’s one thing, but not to support it would be wrong. I want to give back to the sport.”

With that attitude, it's not surprising that when he’s confronted with the accusations that he is in racing only for the money, Spencer is puzzled. “Racing is a relationship to me. Sometimes I hate it, but most of the time I love it.” At Miami he did a little of both. During the first two practice sessions, he circulated the slippery, bumpy course a second or two off the pace of Doug Chandler, who was setting the fast times. When Spencer would hook up with the faster riders, he could stick with them for a lap or two then drop back.

In his heat race, Spencer was gridded on the third row, and after the start, was making his way through the pack when a slower rider unloaded in front of him. “I could see the crash coming,” he says. “The rider was in the corner too hot, so 1 was already moving inside of him when he fell.” Nonetheless, it cost him some time in the five-lap heat, and as a result he started the main event from row five. He got a good start, but the race was red-flagged because of a Turn One crash. On the restart, Spencer’s racing number matched his position, as he dove into the first turn in 19th place.

As Spencer moved up to 15th place, he continued to go faster and look smoother, until the bike crunched to a halt and ended his day in the oppressive Miami heat and humidity. Chandler cruised on to win his third Superbike race in a row while Spencer retired to his motorhome, looking for answers. His father, Fred, stood in the pits, and said to no one in particular, “He needs a little luck to help his confidence.”

Earlier, Spencer had said, “You have to be in the position to go fast and to capitalize on the ability to win.” He has not been able to do that consistently since 1985, but it’s a good bet he will race again, and there’s a chance he may go after another world championship if the right deal comes along. “I’m not interested in another do-or-die effort, but I would like another shot. Once you’ve competed in GPs, it’s hard to race anything else.”

And though what Spencer would like most is to run his own team, he says, “It’s important for me to ride. I’m even doing it on the street for fun for the first time in my life. It was always a business before.” With a team, Spencer could also play a more important role in the promotional and marketing side of racing, which he considers has been mismanaged and bungled. “So much garbage gets in the way of the sport today. When people find out that riders are not biker types out to wreck the town, it will be easier for everyone.” >

It is no longer easy for Spencer. He wants to race, but seems unsure just what his next step should be. He is learning that the physical training and diet of riders today is much more athletic than it was in 1985, and the machinery is more sophisticated. "I'd like the chance to come back and work up to things, but every time I get on a bike, people expect me to win," he laments.

He is unable to do that right now, and he knows that even with his tal ent, it will take a lot of work before he can be competitive again. But it looks like he is willing to take the risk.

“When I consider not racing,” he says, “I only have to remember how I feel when I don’t. When you have done something your whole life, it becomes awfully important.” 0

Clipboard Doug Chandler takes control

A fter David Sadowski won the season-opener Superbike race at Daytona, everyone thought the Vance & Hines team was going to walk away with the championship. But by the second race. Team Muzzy/Kawasaki got things cooking, and now, its main rider, Doug Chandler, has gone on to become the dominant rider in the class.

Chandler finished second behind Doug Polen at Road Atlanta, then cruised to a second overall in the World Superbike round held in Brainerd, Minnesota. He backed that up with a convincing win at Loudon the following week. “We’re just stepping it up as we go,” said Chandler. “We got the bike working great at Road Atlanta, and it keeps getting better.”

Add to that, Chandler’s performance at Miami, where he dominated the rest of the field with a flawless ride, and you get a rider who is just reaching his peak. As a result. Chandler is virtually running away with the AMA championship. If he does go on to win the series, we could well see the launch of yet another top American rider into the ranks of GP racing.

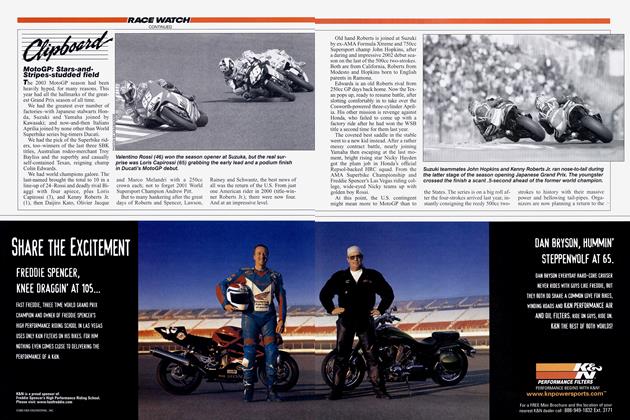

Rumors of a new race series for 1991

One of the frustrating aspects of motorcycle roadracing is that while it is inarguably one of the most exciting motorsports events to watch, it has seldom been televised other than as a once-a-year special or on hard-to-get cable stations.

But if rumors of a new, nonAMA-sanctioned race series turn out to be true, there is a good chance that U.S. racing fans will be able to see an eight-race series on network television in 1991, produced by a company called Moto Du Mond. As of the time Cycle World went to press, nothing was official, but we have found out that the series, designed from its inception for television, and using 250cc two-stroke machines, will feature 10, two-rider teams competing for an alleged $250,000 purse at each event. The organizers claim to have modeled the series on NASCAR, and vow to keep the racing tight.

So far, the organizers claim that the teams, each with a buy-in price of $700,000, have attracted a lot of attention. Bubba Shobert, Wayne Rainey, Kenny Roberts and Eddie Lawson each have expressed interest in a team and negotiations are under way with “big-name” celebrities and sports figures for team ownership. A main sponsor for the series will be named shortly, and the television contracts may be wrapped up by early October.

Negotiations are also under way with Honda, Yamaha and Aprilia, who are said to be ready to increase production of current-model 250cc racebikes to supply the teams.

Not too surprisingly, one of the movers and shakers of this proposed series is Kenny Roberts, and he’s told CW that if the series works in 1991 with 250s, his goal is to move the series up to 500s in 1992, when there should be a larger supply of the crowd-pleasing larger-displacement machinery available.

So Roberts, whose run-ins with both the FIM and the AMA have been well-publicized, may do what neither of those organizations have been able to accomplish: Bring bigtime roadracing to American television audiences on a season-long basis. E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

October 1990 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

October 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

October 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1990 -

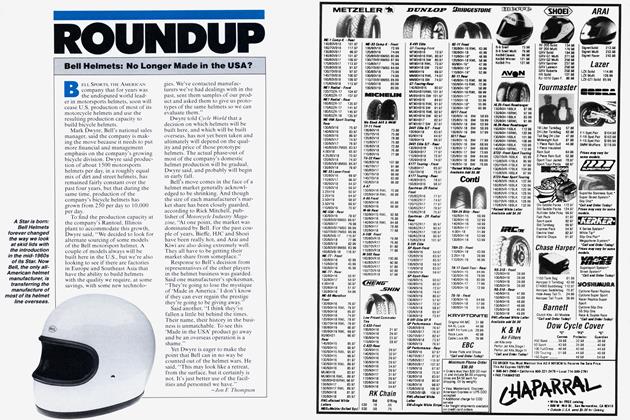

Roundup

RoundupBell Helmets: No Longer Made In the Usa?

October 1990 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupItalian Update: News From Cagiva, Aprilia And Ferrari

October 1990 By Alan Cathcart