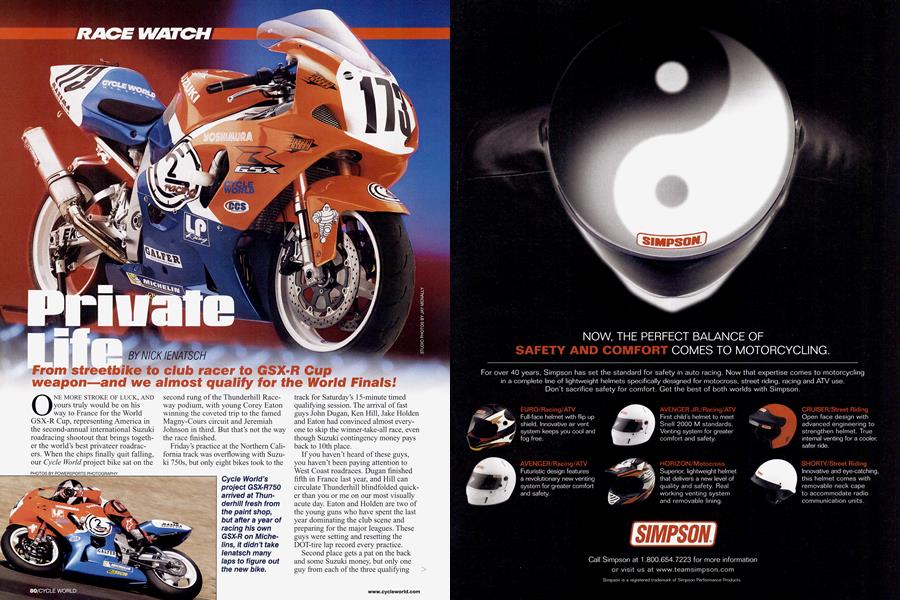

Private Life

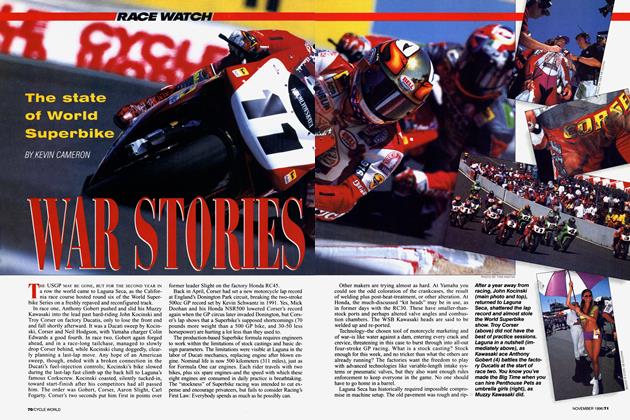

RACE WATCH

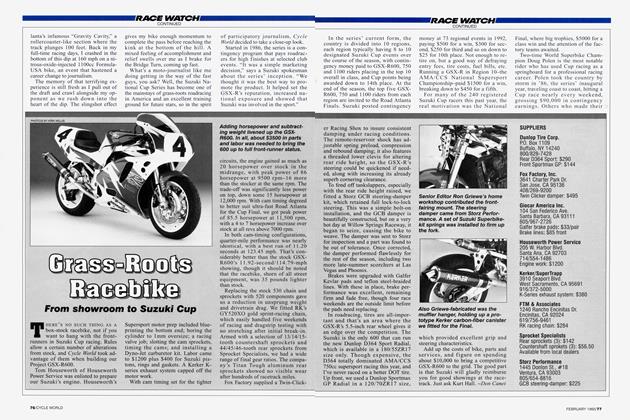

From streetbike to club racer to GSX-R Cup weapon—and we almost qualify for the World Finals!

NICK IENATSCH

ONE MORE STROKE OF LUCK, AND yours truly would be on his way to France for the World GSX-R Cup, representing America in the second-annual international Suzuki roadracing shootout that brings together the world’s best privateer roadracers. When the chips finally quit falling, our Cycle World project bike sat on the second rung of the Thunderhill Raceway podium, with young Corey Eaton winning the coveted trip to the famed Magny-Cours circuit and Jeremiah Johnson in third. But that’s not the way the race finished.

Friday’s practice at the Northern California track was overflowing with Suzuki 750s, but only eight bikes took to the track for Saturday’s 15-minute timed qualifying session. The arrival of fast guys John Dugan, Ken Hill, Jake Holden and Eaton had convinced almost everyone to skip the winner-take-all race, even though Suzuki contingency money pays back to 10th place.

If you haven’t heard of these guys, you haven’t been paying attention to West Coast roadraces. Dugan finished fifth in France last year, and Hill can circulate Thunderhill blindfolded quicker than you or me on our most visually acute day. Eaton and Holden are two of the young guns who have spent the last year dominating the club scene and preparing for the major leagues. These guys were setting and resetting the DOT-tire lap record every practice.

Second place gets a pat on the back and some Suzuki money, but only one guy from each of the three qualifying races held across the country gets to race in the land of Michelin and Monet, as well as nab a Suzuki support deal in 2004. That support consists of the use of a GSX-R750 and a parts budget from Suzuki, but more importantly, it “gets a foot in the door.” Those are the words used by a Suzuki official, and when I pushed for details, he said, “It might not guarantee a factory tryout, but it lets that rider know we are interested in him or her, and would like to include that rider in our future plans.”

With factory rides in short supply, a “foot” in Suzuki’s door could prove invaluable. I’m pretty sure that each of the eight Cup competitors at Thunderhill would like to be teammates with Aaron Yates, Ben Spies or Mat Mladin.

During practice it became clear that Dugan, Eaton, Hill or Holden would win free airfare, but despite all the reasons to watch what would surely be a great race from the grandstands, I figured it would be best to line up on Sunday to see what happened. No use waving the surrender flag before you get in the fight. (And, yeah, just starting the race guaranteed the eighth place payout of $75, roughly double a freelance journalist’s weekly salary!)

Hypercycle head man Carry Andrew and I built my racebike for a five-step hop-up feature in Cycle World’s sister Sportbike annual, walking a stock 2003 Suzuki GSX-R750 through various stages of tune during a track day. Each stage was quantified by the cost of the modification, lap times, rider feedback and front-straight speed, when applicable. In one day we dropped more than 5 seconds from the stock GSX-R750’s lap times, and finished the day by running fairly competitive laps when judged against my usual CCS race times. I’d been competing on a 2001 GSX-R750, and it seemed a natural progression to enter one of the three World GSX-R Cup qualifiers on our project bike, using what we’ve learned from a year on my G2 Racing bike. Andrew morphed the stock ’03 GSX-R into a racer that fit within the CCS Heavyweight Supersport rules, yet made no more than 135 horsepower and weighed no less than 375 pounds.

It’s Suzuki’s habit to back classes similar to Heavyweight Supersport with contingency money, and a points system that allows successful regional racers to qualify for the U.S. Suzuki Cup Final held at Road Atlanta in November. These classes mandate mostly stock bikes on DOT tires, very similar to the AMA Superstock class, and Suzuki runs a Cup final for the GSX-R600, 750 and 1000, as well as the SV650 and 1000, and the TL1000R. It’s a fascinating system of qualification that brings together the quickest club riders from all over more than $80,000 on the line. Future factory stars are bom at the Cup Finals, a tradition that goes back 17 years. I can remember watching one of the first Cup Finals at Southern California’s now defunct Riverside Raceway, and marveling at the genius of bringing together a nation of riders on similar equipment. Cheating was mmored to be rampant back then, but the increased availability or rear-wheel dynos has been a huge step toward leveling the playing field.

My G2 racebike works well enough to get me to the front of the CCS pack in the Pacific and Southwest divisions, but weighs too little and makes too much power for this Cup race (Andrew built it, too). My racer served as a starting point and provided plenty of setup information for the project bike, including a few vital pieces. Every practice session was an improvement as I learned the intricacies of racing at Thunderhill, where it takes almost 2 minutes to complete a quick lap.

I qualified fifth behind the previously mentioned fast guys, with my teammate Andre Castaños sixth, Johnson seventh and the CCS Pacific region’s numbertwo plate holder Corey Sarros eighth. Dugan had grabbed pole position with a new class record of 1:52.9, but Hill, Holden and Eaton were all right there. The GSX-R Cup isn’t open to factorysupported riders and it was clear that the stakes in this game were very high for the amateur Experts. Suzuki pours more than $1.5 million into its contingencysupport program and this small-but-select field had already gathered more than its share of the company’s offerings. Now, in a single, six-lap dash, fame, fortune and a ride for next year were on the line.

The words “fame” and “fortune” might sound extreme when describing a regional roadrace, but Suzuki’s GSX-R Cup Series has a way of making names big. One of the best examples is a Texan named Doug Polen, who careened around the nation in an old van, unloading well-used GSX-Rs to kick butt from Willow Springs to Road Atlanta. Suzuki contingency money helped Polen get through the tough amateur years until factories paid him to ride and win championships. Scott Russell, Aaron Yates, Britt Turkington, Kurt Hall.. .all are racing heroes who stormed to factory rides through Suzuki’s Cup series. And if you begin looking at the names that collected Suzuki contingency checks over the years, the list includes Nicky Hayden, John Hopkins, Jason Di Salvo, Miguel Duhamel, Jason Pridmore and even CVTs Road Test Editor Don Canet. Morgan Broadhead, Suzuki’s Sports Promotions On-Road Specialist, put the company’s contingency deal into perspective when he told me, “Fifteen of the current 30 factory and factory-supported AMA riders came up riding GSX-R750s for Suzuki cash. The 750cc Supersport class has become the training ground for factory stars.”

The Thunderhill pole-sitter definitely had his GSX-R750 figured out. The middle Gixxer is a bike that splits the difference between the point-and-shoot 1000 and the momentum-over-all 600. Dugan came down from Washougal, Washington, for another shot at Magny-Cours “Man, I loved it last year,” Dugan enthused. “You show up and they’ve got a brand-new bike waiting, with just break-in mileage on it. You get three sets of Michelin Pilot Races, one extra rear sprocket, a pipe and some fork springs. If you’re good at jumping on a stock streetbike and going quick, you’ll love this race.”

Broadhead came to Thunderhill armed with a Dynojet dyno and a set of digital scales, warning us in a special rider’s meeting that the horsepower and weight numbers were absolute. The dyno was open until noon on Sunday to help fine-tune the power delivery beneath 135 horsepower, and Andrew ran our bike several times immediately following some of the other CCS races I competed in. Hot oil, hot exhaust system. . .all those things make a difference and Andrew knows it.

Our machine went from streetbike to racebike in a very short time, but Andrew knows a thing or two about building fast Supersport bikes. He dipped into the Yoshimura catalogue for a head gasket, camchain sprockets, exhaust system, EMS and ECU with a quick-shifter, crash sliders and a fairing bracket, and added an APE manual camchain tensioner to complete the engine upgrades. Chassis mods included the old Ohlins shock from my racebike and a K-Tech 20mm damper kit for smoother action and finer percycle rearsets, a Toby steering damper and Spiegler brake lines also were fitted, as well as a #520 EK chain running on AFAM sprockets. Andrew painted the AirTech bodywork in traditional Hypercycle colors and added a Zero Gravity windscreen, then spooned on a set of Michelin Pilot Race tires (S2 front, M2 rear) to create an extremely capable production racer.

In racing, it’s sometimes better to be lucky than good, and luck hugged me with both arms on Sunday. I launched hard off the second row, but the front row launched better and I settled into fifth place, being pushed by Johnson and Castaños. Halfway into the race, Hill and Eaton bumped without crashing in Turn 11, and Dugan crashed avoiding them. That put me fourth. A lap later Hill locked the front wheel on the brakes into Turn 14, and suddenly I was fighting Johnson for the final podium spot. And the drama wasn’t over.

Jake Holden pulled a tiny gap on Eaton and held it to the line, while I barely outpaced Johnson for third. I wheeled the CIE bike into the winner’s circle and we all waited while Holden’s Gixxer spun the Dynojet’s drum. The dyno operator runs the bike as many times as necessary, quitting when the horsepower numbers begin to fall. I wasn’t paying too much attention, until Broadhead walked over to the 20-yearold Holden, put his hand on the kid’s shoulder and said, “Jake, I’m really sorry, but your bike is over. You’re out.” Nobody could believe it, but moments later Eaton’s bike was rolled onto the dyno and Holden trudged toward his pit. Holden’s 135.2-horsepower run had handed me second place.

“You’re the luckiest S.O.B. I know,” my old buddy Terry Newby stated.

My run of luck stopped there, but I ain’t complainin’. I got to spray champagne and be in the record books as second place in a World GSX-R Cup qualifier, despite the fact that I was the fifth-quickest GSXR750 racer at Thunderhill on that day. Winner-take-all races create a “win-orcrash” mentality that my 42-year-old mind just can’t grasp. Both Holden and Eaton had a few major “moments” during the six-lap sprint, both of them out of the seat and out of shape while running laps in the 1:52 range, both pushing beyond the edge in hopes of getting the huge payoff. It was quite a show, and these kids speak volumes for the grass-roots success of Suzuki’s contingency program. After an inspired ride, two crashes and one dyno blowout, 16year-old Corey Eaton will fly to France and battle with the best GSX-R750 riders in the world as another step in what this young rider hopes is a climb to an AMA or FIM championship ride. But you can be sure Jake Holden’s GSX-R750 will be legal when he seeks redemption in the Suzuki Cup Finals at Road Atlanta this fall. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue