WAR STORIES

RACE WATCH

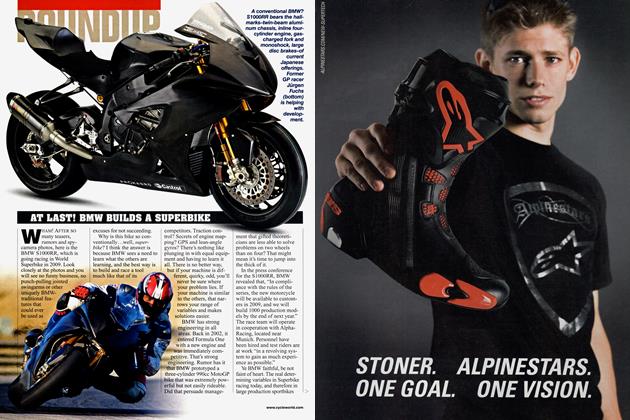

The state of World Superbike

KEVIN CAMERON

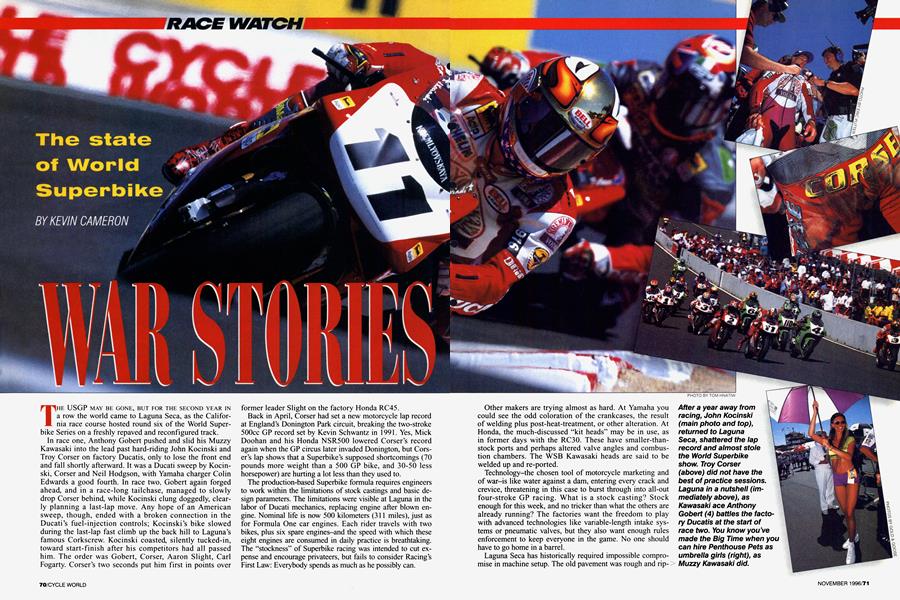

THE USGP MAY BE GONE, BUT FOR THE SECOND YEAR IN a row the world came to Laguna Seca, as the California race course hosted round six of the World Superbike Series on a freshly repaved and reconfigured track.

In race one, Anthony Gobert pushed and slid his Muzzy Kawasaki into the lead past hard-riding John Kocinski and Troy Corser on factory Ducatis, only to lose the front end and fall shortly afterward. It was a Ducati sweep by Kocinski, Corser and Neil Hodgson, with Yamaha charger Colin Edwards a good fourth. In race two, Gobert again forged ahead, and in a race-long tailchase, managed to slowly drop Corser behind, while Kocinski clung doggedly, clearly planning a last-lap move. Any hope of an American sweep, though, ended with a broken connection in the Ducati’s fuel-injection controls; Kocinski’s bike slowed during the last-lap fast climb up the back hill to Laguna’s famous Corkscrew. Kocinski coasted, silently tucked-in, toward start-finish after his competitors had all passed him. The order was Gobert, Corser, Aaron Slight, Carl Fogarty. Corser’s two seconds put him first in points over

former leader Slight on the factory Honda RC45.

Back in April, Corser had set a new motorcycle lap record at England’s Donington Park circuit, breaking the two-stroke 500cc GP record set by Kevin Schwantz in 1991. Yes, Mick Doohan and his Honda NSR500 lowered Corser’s record again when the GP circus later invaded Donington, but Corser’s lap shows that a Superbike’s supposed shortcomings (70 pounds more weight than a 500 GP bike, and 30-50 less horsepower) are hurting a lot less than they used to.

The production-based Superbike formula requires engineers to work within the limitations of stock castings and basic design parameters. The limitations were visible at Laguna in the labor of Ducati mechanics, replacing engine after blown engine. Nominal life is now 500 kilometers (311 miles), just as for Formula One car engines. Each rider travels with two bikes, plus six spare engines-and the speed with which these eight engines are consumed in daily practice is breathtaking. The “stockness” of Superbike racing was intended to cut expense and encourage privateers, but fails to consider Racing’s First Law: Everybody spends as much as he possibly can.

Other makers are trying almost as hard. At Yamaha you could see the odd coloration of the crankcases, the result of welding plus post-heat-treatment, or other alteration. At Honda, the much-discussed “kit heads” may be in use, as in former days with the RC30. These have smaller-thanstock ports and perhaps altered valve angles and combustion chambers. The WSB Kawasaki heads are said to be welded up and re-ported.

Technology-the chosen tool of motorcycle marketing and of war-is like water against a dam, entering every crack and crevice, threatening in this case to burst through into all-out four-stroke GP racing. What is a stock casting? Stock enough for this week, and no tricker than what the others are already running? The factories want the freedom to play with advanced technologies like variable-length intake systems or pneumatic valves, but they also want enough rules enforcement to keep everyone in the game. No one should have to go home in a barrel.

Laguna Seca has historically required impossible compromise in machine setup. The old pavement was rough and rip> pled, and there were sharp transitions between old and new. A good hook-up on rough stuff requires springs and damping on the soft side to isolate the machine from the busy surface. But hitting the bottom of the Corkscrew requires enough compression damping and/or spring to absorb the impact. Pick your poison: Run it soft and lose time in the Corkscrew, trying not to bottom and slide; run it hard and skate

on the rough stuff, losing time on corner exits and transitions. New pavement was supposed to ease this compromise, but it created as many fresh ripples as it erased old ones. Laguna remains non-trivial.

Powerband and handling are two sides of the same coin. The more power per cubic inch you make, the peakier your engine becomes. Motorcycles have limited traction, so they accelerate fastest with broad, smooth power that pushes rather than hits. The harder your engine hits, the more your tires slip-and-grip, and the stiffer you must make your chassis. To keep the front wheel steering even when the engine’s hit yanks it upward, you shove weight to the front of the machine. Ducati, whose big engine pushes rather than hits, can afford a softer chassis and a less extreme weight distribution.

Is the Ducati a brilliant example of balanced design, or is it a happy anachronism whose time has accidentally come? It doesn’t really matter, because Ducatis do everything well.

Action on the new ripples between Turns 9 and 10 illustrated this. Ridden hard by Gobert, Slight or Edwards, four-cylinder 750s were upset into disturbing wiggles. Going equally fast, the Ducatis of Corser, Kocinski and Hodgson hardly noticed those same ripples. Big difference.

Another illustration was the uphill back straight leading to the top of the Corkscrew. Ability to lift the front wheel is affected by the nature of the power. It’s easier not to wheelie when you have very smooth power, but wheelies are impossible to avoid if your power is peaky. As I stood watching, the Hondas of Miguel Duhamel, Slight and Carl Fogarty wheelied the whole way up, while Gobert’s Kawasaki and Edwards’ Yamaha wheelied only here and there. Of the Ducatis, only Corser’s showed occasional daylight under its front wheel. None of the top bikes had a killer power advantage-there was no passing here. This tells us that the top four-cylinder bikes have a lot of power, but the wheelies show that their power isn’t entirely smooth. The top Ducatis, no slower, are smooth.

With the visible traction-breaking effect of pavement ripples on the fourcylinder bikes, it was easy to believe what was being said about the new 16.5-inch rear tires-that they were worth from a half to a second-and-ahalf per lap. Why? These new tires are just as big around as the 17s they re-

place, but there is more rubber between the rim and the road. The extra rubber in that taller sidewall acts as supplementary suspension, helping suspension and chassis flex to absorb bumps, preventing loss of traction.

Tire manufacturers make tall-sidewall tires whenever the chassis and suspension people throw in the towel. Back in 1971, Dunlop offered its tailwall 350M tire as a band-aid for the barely controllable two-stroke Kawasaki H1R. Goodyear used taller, softer sidewalls in its 1455 tire of 1975 to deal with too much power and too little suspension in the twin-shock Yamaha TZ750-C. The idea reappeared in the Goodyear tires of 197879. In these bias-ply designs, the increased flex came at a price, though: delayed steering response and a feeling like loose swingarm bearings. Perhaps in today’s radial construction, this compromise is eliminated.

Every discipline has its icons. Chassis stiffness has long been an icon in motorcycle design. At the end of the 1980s, 160-horsepower GP bikes had violent power that forced designers to adopt much-stiffened chassis and extreme forward weight placement. Chassis stiffness cut the violence and duration of the wobbles that resulted from off-corner slip-and-grip acceleration. Because it worked then, stiffness became god. Forward engine placement,

because it kept front tires on the ground and steering, became a sub-god.

Times changed but design did not. Electronic controls softened 500 power delivery, but chassis people continued adding stiffness as always, until Wayne Rainey’s super-stiff 1993 YZR500 Yamaha developed, in his words, “chatter, skating and hop.” It had become so stiff that, when leaned over in a turn, it lacked the flexibility to assist the suspension in the job of absorbing bumps. No longer being absorbed by any compliant member, the bumps knocked the bike around, preventing it from hooking up.

Right now, engineers are busily tearing down these false gods, measuring chassis stiffness, resolving it into coordinates, building families of test chassis with graduated stiffness. As is usual

when no one knows the answers in a hot new area, a million things are being tried, and tall-sidewall tires are only one. Another is spring/damper rates that soften as the machine settles in a turn. Another is smaller, more flexible fork tubes. Yet another is to design flex into chassis elements, as with the open-backed swingarm-pivot plates of the 1996 Honda CBR900RR, or the similar but longer plates on Yamaha’s ’96 TZ250 racebike. Leading-edge bicycle engineers see the future, not in complex linkages, dampers and more parts, but in structures (likely non-metallic) with engineered flexure and damping properties. They may have fresh answers for motorcycle racing.

But wait. How can World Superbikes, with less power and more weight than 500s, equal some GP-bike lap records? Power characteristics and chassis are inseparable. GP bikes are specialized for handling a lot of power, and they are very good at that. They are less good at delivering less. Their engines, although much-improved over their worst years (198889), cannot deliver low power as smoothly as a four-stroke can. This al-

lows Superbike riders to begin acceleration earlier and control it better in the crucial early stages of corner exit.

Even weight is not entirely a penalty. Kel Carruthers used to say that a bike handles better under a heavier rider. Why? Because the heavier rider/bike combo is whacked about less by bumps. The motions of a pair of 30-pound wheels disturb a 356pound Superbike a bit less than they do a 286-pound GP machine.

How goes the WSB horsepower race? Ducati reliability is fading as the design is revved harder. For a time, it appeared that Ducati ran big motors

(almost lOOOcc) on acceleration courses, relying on lower average revs to make the inertia forces of their heavier pistons tolerable. On faster courses, smaller-displacement engines (955cc) with lighter pistons, revving higher, could deliver more power. Now, as the Japanese Fours receive increasing R&D, every part of the Ducatis must be hammered harder to equal them. Every part has its limit. There are two basic approaches to four-cylinder power. At present, engineers are trying to up power by raising the rev ceiling, while adding devices to prevent greater power from also becoming narrower power. Such devices have included mapped ignitions, Yamaha’s EXUP and the present variable intake-length systems. Even more powerband width and peak power can be expected soon from wide-range variable valve-timing systems (VVT). Such systems boost bottom torque by shortening valve timing at lower revs to Harley-like figures, then boost top-end by extending valve timing at high revs to Bonneville Salt Flats numbers. Honda has manufactured a two-stage system employing multiple cam lobes, with a shifting device to switch between low-speed and high-speed lobes appropriately. A three-stage system is said to be in the works. But the holy grail in this area is completely variable valve timing and lift, under computer control. This would provide timing that ensured maximum cylinder-filling at every rpm, delivering smooth, creamy power of the kind that tires love best. Engineers everywhere are listening to outfits like Aura Systems in El Segundo, California, which proposes to deliver just that. The Aura electromagnetic valve system is rumored to have a 5000-to-6000-rpm ceiling at present, but development will raise this.

Another approach to horsepower is to optimize the engine for best power at a fixed rpm, and then deliver it through a so-called continuously variable transmission (CVT), similar in concept to the variable drives used on snowmobiles.

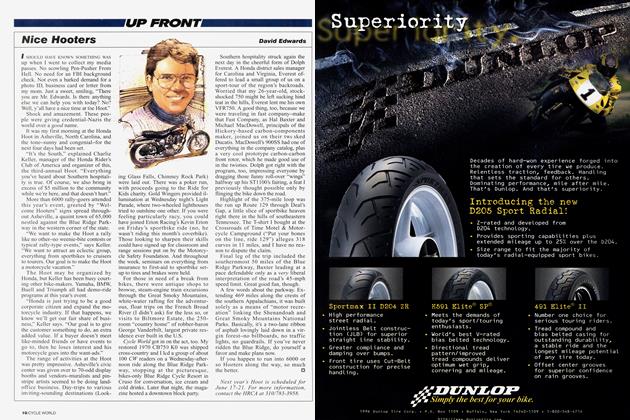

Rider changes in World Superbike suggest other questions. Carl Fogarty, the 1994-95 WSB Champion on Ducati, has spent this season trying to come to grips with the less-forgiving, altogetherdifferent Honda. That makes sense, but what about Mike Hale, who starred here at Laguna a year ago on a Honda? Now Ducati-mounted, he cannot seem to make an impression in WSB.

How did our U.S. Superbike stars fare against the WSB men? A year ago here, Hale and Duhamel dominated the early laps of both races on Camel Hondas, only to fade with their second-level tires. This year, with access to the best rubber, there were high hopes for Duhamel. Alas, he pitted early for a tire change in race one, and crashed in the second. His close rival in U.S. Superbike, Doug Chandler, was out with brake trouble in race one, finished sixth in race two. Eraldo Ferraci’s U.S.-based Ducati team did not fare well at all, while the Vance & Hines Yamaha and Yoshimura Suzuki squads simply stayed home.

As agreeable as Kocinski’s race-one win is, it’s unpleasant to see our national Superbike riders struggle with the equipment differences between their rules and WSB. Getting the good tires is fine, but our riders must then waste practice time trying to learn what the WSB teams already know. And variable intake-length systems are legal in the FIM’s WSB, illegal in our AMA series. Can we expect a single set of Superbike rules any time soon? The best that can be said is that it’s under discussion-as it should be. Œ

View Full Issue

View Full Issue