CYCLE WORLD 1962-2002 retrospective

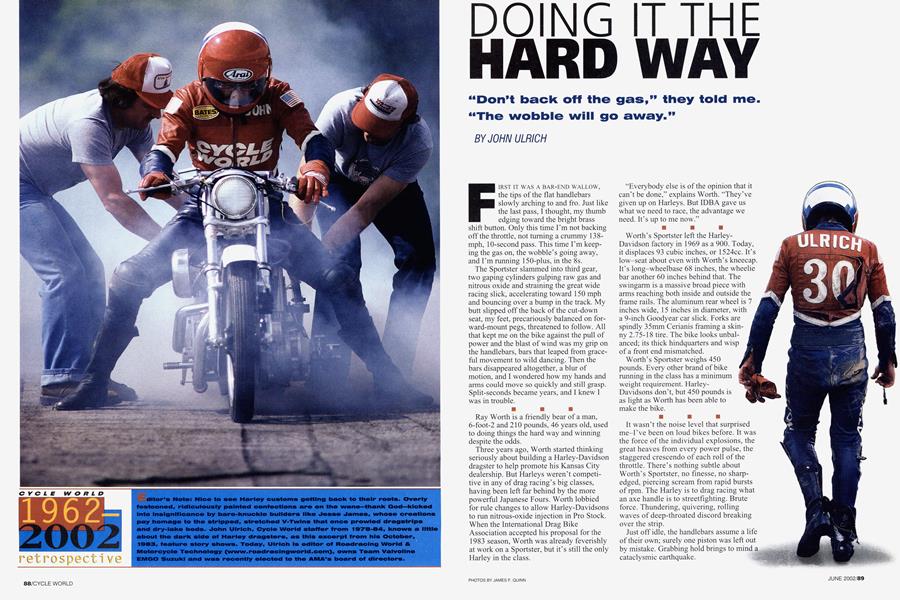

Editor's Note: Nice to see Harley customs getting back to their roots. Overly festooned, ridiculously painted confections are on the wane-thank God-kicked into insignificance by bare-knuckle builders like Jesse James, whose creations pay homage to the stripped, stretched V-Twins that once prowled dragetrips and dry-lake beds. John Ulrich, Cycle World stafter from 1978-04, knows a little about the dark side of Harley dragsters, as this excerpt from his October, 1983, feature story shows. Today, Ulrich is editor of Roadracing World & Motorcycle Technology (www.roadracingworld.com), owns Team Valvoline EMGO Suzuki and was recently elected to the AMA'S board of directors.

DOING IT THE HARD WAY

“Don’t back off the gas,” they told me. “The wobble will go away.”

JOHN ULRICH

FIRST IT WAS A BAR-END WALLOW, the tips of the flat handlebars slowly arching to and fro. Just like the last pass, I thought, my thumb edging toward the bright brass shift button. Only this time I’m not backing off the throttle, not turning a crummy 138mph, 10-second pass. This time I’m keeping the gas on, the wobble’s going away, and I’m running 150-plus, in the 8s.

The Sportster slammed into third gear, two gaping cylinders gulping raw gas and nitrous oxide and straining the great wide racing slick, accelerating toward 150 mph and bouncing over a bump in the track. My butt slipped off the back of the cut-down seat, my feet, precariously balanced on forward-mount pegs, threatened to follow. All that kept me on the bike against the pull of power and the blast of wind was my grip on the handlebars, bars that leaped from graceful movement to wild dancing. Then the bars disappeared altogether, a blur of motion, and I wondered how my hands and arms could move so quickly and still grasp. Split-seconds became years, and I knew I was in trouble.

Ray Worth is a friendly bear of a man, 6-foot-2 and 210 pounds, 46 years old, used to doing things the hard way and winning despite the odds.

Three years ago, Worth started thinking seriously about building a Harley-Davidson dragster to help promote his Kansas City dealership. But Harleys weren’t competitive in any of drag racing’s big classes, having been left far behind by the more powerful Japanese Fours. Worth lobbied for rule changes to allow Harley-Davidsons to run nitrous-oxide injection in Pro Stock. When the International Drag Bike Association accepted his proposal for the 1983 season, Worth was already feverishly at work on a Sportster, but it’s still the only Harley in the class.

“Everybody else is of the opinion that it can’t be done,” explains Worth. “They’ve given up on Harleys. But IDBA gave us what we need to race, the advantage we need. It’s up to me now.”

Worth’s Sportster left the HarleyDavidson factory in 1969 as a 900. Today, it displaces 93 cubic inches, or 1524cc. It’s low-seat about even with Worth’s kneecap It’s long-wheelbase 68 inches, the wheelie bar another 60 inches behind that. The swingarm is a massive broad piece with arms reaching both inside and outside the frame rails. The aluminum rear wheel is 7 inches wide, 15 inches in diameter, with a 9-inch Goodyear car slick. Forks are spindly 35mm Cerianis framing a skinny 2.75-18 tire. The bike looks unbalanced; its thick hindquarters and wisp of a front end mismatched.

Worth’s Sportster weighs 450 pounds. Every other brand of bike running in the class has a minimum weight requirement. HarleyDavidsons don’t, but 450 pounds is as light as Worth has been able to make the bike.

It wasn’t the noise level that surprised me-I’ve been on loud bikes before. It was the force of the individual explosions, the great heaves from every power pulse, the staggered crescendo of each roll of the throttle. There’s nothing subtle about Worth’s Sportster, no finesse, no sharpedged, piercing scream from rapid bursts of rpm. The Harley is to drag racing what an axe handle is to streetfighting. Brute force. Thundering, quivering, rolling waves of deep-throated discord breaking over the strip.

Just off idle, the handlebars assume a life of their own; surely one piston was left out by mistake. Grabbing hold brings to mind a cataclysmic earthquake.

And the clutch-regular rider Joe Yeager must be an ox! The clutch pull had me casting eyes around the pits, looking for a piece of pipe to slip over the lever. I never did figure out how I was going to slip it at launch, but somehow it slipped, and I jolted forward on the roughest, wildest, leastin-control ride of my life. Mechanical bull, hah! HarleyDavidson!

Above the roar of the engine comes a new noise—errch, errch, errch-the front tire leaving S-shaped skidmarks before the timing lights. The bike rocks left and right, the tire noise gaining tempo and volume, the horizon tilting crazily this way and that. I can’t do a thing about it, out of control, along for the ride, wondering where it’s gonna end and waiting, waiting, waiting as the bike snakes and rocks and the tire chirps and chirps and chirps again. The rocking exaggerates, the Harley finally leaning so far left that the footpeg digs into the pavement and is ripped off, taking a chunk of the primary cover with it. My left foot swings back from the force of hitting the strip, and suddenly I’m rolling off the right side of the motorcycle, the deep blue sky catching my eye before I hit the wheelie bars and bounce forward, the awful, grinding, shussing noise of metal on pavement and leather on pavement engulfing me. The engine is silent. Parts of my body feel heat as leather wears thin. I’m sliding at an impossible rate, on my back, looking at the sky amid the din of crashing.

A dark shape fills my faceshield and the Sportster races by, leaving in its wake a barrage of oil and asphalt chips, dust and debris, ground aluminum and steel and fiberglass. Then it’s gone and I’m left with just the sounds of my leather suit and gloves and boots slewing down the track.

I pivot slowly as I slide, turning gentle 360s on my back, and try to raise an elbow or wrist when the heat is too intense, spreading the load in the hopes of minimizing damage.

The slide stops and silence, a blanket, descends. My faceshield is coated with oil and grit. In the distance I hear a pit bike start, rev madly through the gears, and head toward me, its engine screaming.

I lie on the track, moving an arm, an ankle, a knee, toes, a leg, feeling for damage. I find it in my left collarbone, twice broken last year, in the form of a new wobble, a joint where there’s not supposed to be one.

The pit bike’s rabid drone is near, and Worth skids to a halt, shouting, “Are you all right? Are you all right?”

“Sorry about your bike, Ray.” It’s all I can say.

“Never mind the bike,” he says, frantic. “We can fix the bike. What about you?”

We find the bike another 300 feet down the track, in the grass, the front wheel gone, the fork locks snapped on both sides from the violent shaking. They were right. The wobble did go away. It just took longer than I expected.

Yeager drives up in his van. He looks at what’s left of the Sportster, and at me.

“You went through the traps at 139 mph, turned a 10.20,” he says. “Not bad for a man without a bike.” □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontDaytona, Dimming

June 2002 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Steam-Shovel And A Piece of Earth

June 2002 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCAll In A Row

June 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

June 2002 -

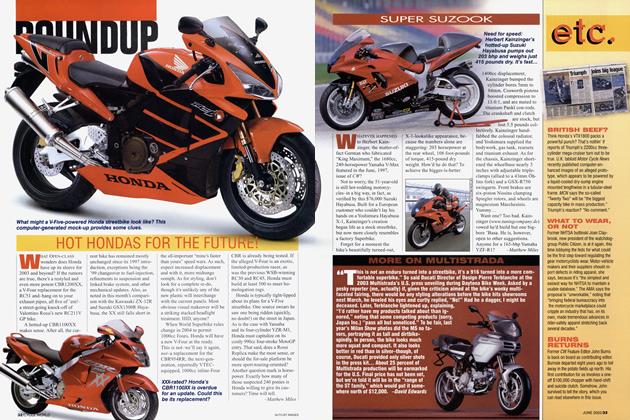

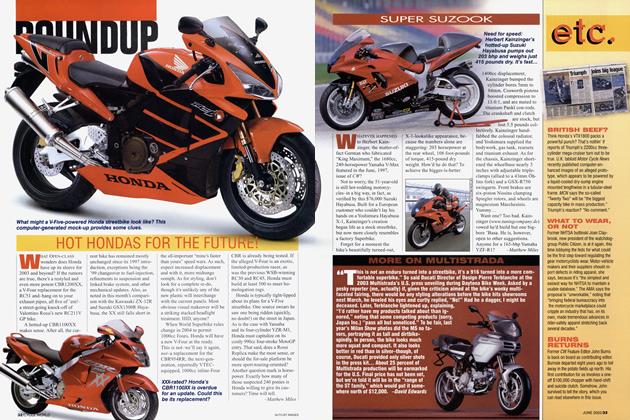

Roundup

RoundupHot Hondas For the Future!

June 2002 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupSuper Suzook

June 2002 By Matthew Miles