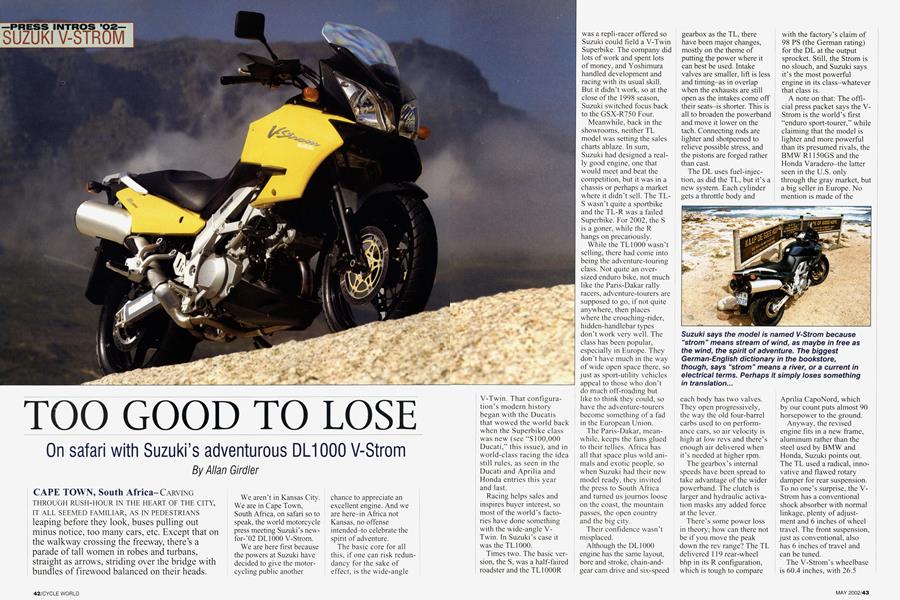

TOO GOOD TO LOSE

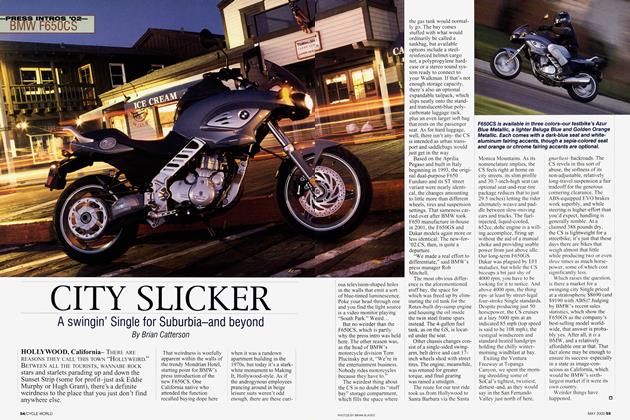

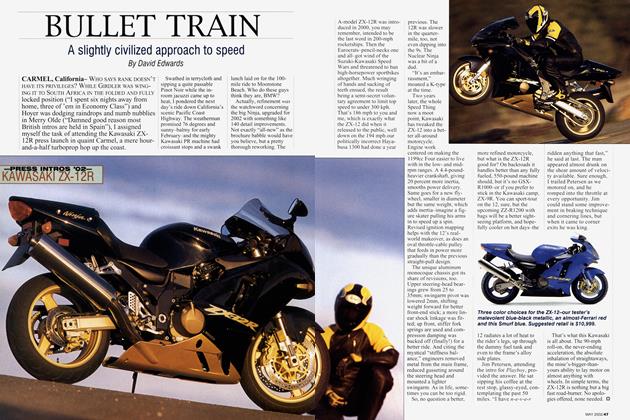

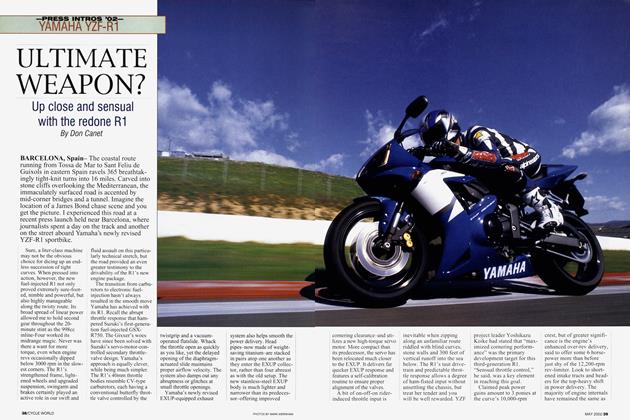

—PRESS INTROS '02—

SUZUKI V-STROM

On safari with Suzuki's adventurous DL1000 V-Strom

Allan Girdler

CAPE TOWN, South AFRICA-CARVING

THROUGH RUSH-HOUR IN THE HEART OF THE CITY, IT ALL SEEMED FAMILIAR, AS IN PEDESTRIANS leaping before they look, buses pulling out minus notice, too many cars, etc. Except that on the walkway crossing the freeway, there’s a parade of tall women in robes and turbans, straight as arrows, striding over the bridge with bundles of firewood balanced on their heads.

We aren't in Kansas City. We are in Cape Town,

South Africa, on safari so to speak, the world motorcycle press meeting Suzuki’s newfor-’02 DL 1000 V-Strom.

We are here first because the powers at Suzuki have decided to give the motorcycling public another

chance to appreciate an excellent engine. And we are here-in Africa not Kansas, no offense intended-to celebrate the spirit of adventure.

The basic core for all this, if one can risk redundancy for the sake of effect, is the wide-angle V-Twin. That configuration’s modern history began with the Ducatis that wowed the world back when the Superbike class was new (see “$100,000 Ducati,” this issue), and in world-class racing the idea still rules, as seen in the Ducati and Aprilia and Honda entries this year and last.

Racing helps sales and inspires buyer interest, so most of the world’s factories have done something with the wide-angle VTwin. In Suzuki’s case it was the TL1000.

Times two. The basic version, the S, was a half-faired roadster and the TL1000R was a repli-racer offered so Suzuki could field a V-Twin Superbike. The company did lots of work and spent lots of money, and Yoshimura handled development and racing with its usual skill. But it didn’t work, so at the close of the 1998 season, Suzuki switched focus back to the GSX-R750 Four.

Meanwhile, back in the showrooms, neither TL model was setting the sales charts ablaze. In sum,

Suzuki had designed a really good engine, one that would meet and beat the competition, but it was in a chassis or perhaps a market where it didn’t sell. The TLS wasn’t quite a sportbike and the TL-R was a failed Superbike. For 2002, the S is a goner, while the R hangs on precariously.

While the TL1000 wasn’t selling, there had come into being the adventure-touring class. Not quite an oversized enduro bike, not much like the Paris-Dakar rally racers, adventure-tourers are supposed to go, if not quite anywhere, then places where the crouching-rider, hidden-handlebar types don’t work very well. The class has been popular, especially in Europe. They don’t have much in the way of wide open space there, so just as sport-utility vehicles appeal to those who don’t do much off-roading but like to think they could, so have the adventure-tourers become something of a fad in the European Union.

The Paris-Dakar, meanwhile, keeps the fans glued to their tellies. Africa has all that space plus wild animals and exotic people, so when Suzuki had their new model ready, they invited the press to South Africa and turned us journos loose on the coast, the mountain passes, the open country and the big city.

Their confidence wasn’t misplaced.

Although the DL1000 engine has the same layout, bore and stroke, chain-andgear cam drive and six-speed gearbox as the TL, there have been major changes, mostly on the theme of putting the power where it can best be used. Intake valves are smaller, lift is less and timing-as in overlap when the exhausts are still open as the intakes come off their seats-is shorter. This is all to broaden the powerband and move it lower on the tach. Connecting rods are lighter and shotpeened to relieve possible stress, and the pistons are forged rather than cast.

The DL uses fuel-injection, as did the TL, but it’s a new system. Each cylinder gets a throttle body and

each body has two valves. They open progressively, the way the old four-barrel carbs used to on performance cars, so air velocity is high at low revs and there’s enough air delivered when it’s needed at higher rpm.

The gearbox’s internal speeds have been spread to take advantage of the wider powerband. The clutch is larger and hydraulic activation masks any added force at the lever.

There’s some power loss in theory; how can there not be if you move the peak down the rev range? The TL delivered 119 rear-wheel bhp in its R configuration, which is tough to compare with the factory’s claim of 98 PS (the German rating) for the DL at the output sprocket. Still, the Strom is no slouch, and Suzuki says it’s the most powerful engine in its class-whatever that class is.

A note on that: The official press packet says the VStrom is the world’s first “enduro sport-tourer,” while claiming that the model is lighter and more powerful than its presumed rivals, the BMW R1150GS and the Honda Varadero-the latter seen in the U.S. only through the gray market, but a big seller in Europe. No mention is made of the

Aprilia CapoNord, which by our count puts almost 90 horsepower to the ground.

Anyway, the revised engine fits in a new frame, aluminum rather than the steel used by BMW and Honda, Suzuki points out. The TL used a radical, innovative and flawed rotary damper for rear suspension. To no one’s surprise, the VStrom has a conventional shock absorber with normal linkage, plenty of adjustment and 6 inches of wheel travel. The front suspension, just as conventional, also has 6 inches of travel and can be tuned.

The V-Strom’s wheelbase is 60.4 inches, with 26.5 degrees rake, longer and more relaxed than the TL’s measurements. The new model has a 19-inch front wheel, against the 17 used on the TL, while both models have 17-inch rears. The larger, thinner and taller front tire is one of the cues Suzuki is using to tell the potential buyer what the new model is about.

The design team was at the launch and provided details. For instance, the front wheel, the higher and wider bars, the luggage rack instead of a bumblebee tailsection and the dirtbikestyle handguards were all provided to give a hint of enduro style-never mind the Strom is intended primarily for asphalt running.

The half-fairing gives touring-level protection while not being a full cover as on a sportbike, but the canted mufflers high in the tail tell the onlooker this machine is for sport. The fuel tank, of course, isn’t where it looks to be, but it’s big-5.8 gallons-and ought to give a range beyond 200 miles per stop, no minor feature for the open road.

The record should show here that the motorcycle in this adventure was built to EU rules, so it has some emissions stuff, a catalytic converter for instance, that the U.S. version won’t have. And the EU models will have “position lights,” running lights we’d call ’em, and that in turn allows (shock, gasp) an on/off switch for the headlights. Honest.

This came to light (sorry) when one of our group was flagged down by a traffic marshal who demanded, in Afrikaans so a translator was required, that the headlights be turned on. No problem, but the rider hadn’t seen a motorcycle with a headlight switch for 25 years.

Which brings us to the actual ride.

The precise definition of “enduro,” “touring” or “sport” has never quite been pinned down. Nor do we have any solid performance figures, which won’t be available until a complete test can be conducted. What we have here, though, is a motorcycle that works under as broad a variety of conditions as it’s possible to find.

Sportbikes, especially the derivations of the track versions, work well at speeds, but are wretchedly awkward off the track for more than brief, adrenalinepacked intervals. Most cruisers are comfortable only when parked in front of sports bars, and dressers need reverse gear or training wheels in city traffic. (Okay, that’s all a bit broad-brushed, but you get the idea.)

The practical advantage of debuting the V-Strom in South Africa is that the Cape Town area, the southern tip of the African continent, is like California in that it’s got a tremendous variety of terrain in a relatively small area. We went through the bustling city to the beachfront resorts, the winding roads along the ocean, over the mountains to the wine country and farms, just about everything a touring rider will find anywhere in the world, dirt trails and bad road excepted.

The V-Strom worked everywhere it went. Wind protection is fine up to 90 mph or so, while the narrow engine allows a narrow frame, so the seat isn’t as high as the numbers suggest. The pegs, the bars and grips are where they should be, and the posture keeps weight off wrists and the back.

What Suzuki has done, after all the marketing research and searching for a way to keep a good engine in production, is deliver a marvelous all-around motorcycle that will go anywhere a rider wants, effortlessly.

The V-Strom suits the spirit of adventure, which is surely why we all got on this bus in the first place. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMad Max Found!

May 2002 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Trip To the Barber

May 2002 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCRoom At the Top

May 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

May 2002 -

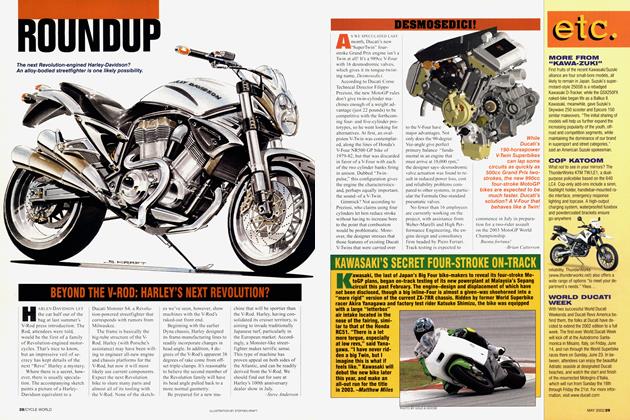

Roundup

RoundupBeyond the V-Rod: Harley's Next Revolution?

May 2002 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupDesmosedici!

May 2002 By Brian Catterson