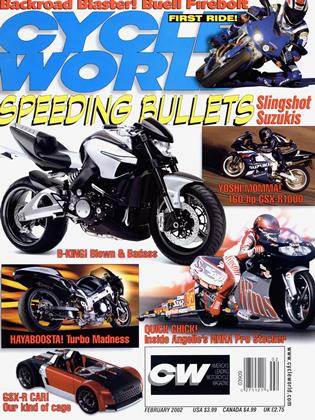

Time Machines

Past and present collide as road-racing legend Wes Cooley samples a pair of street-legal Suzuki Superbikes

BRIAN CATTERSON

NEXT TIME YOU FIND YOURSELF STARING AT THE Suzuki sportbike in your garage, spare a thought for Wes Cooley.

In the formative years of production-based Superbike racing, Cooley and his peers were sort of two-wheeled Chuck Yeagers, risking life and limb piloting dangerous, untested machines at absurd velocities. This occurred to me while pondering a feature story for this special `Suzuki Speed" section. What better way to celebrate the performance of today's street-legal Superbikes than to invite one of the sport's pioneers to test-ride them? Even better if it was someone who had been away from bikes for a while.

"I haven't ridden a motorcycle in five years," Cooley con fessed when we met one November morning at Willow Springs International Raceway. Then, eyeballing the Suzuki GSXI300R Hayabusa and GSX-Rl000 I'd brought tbr him to ride, he added, almost apologetically, "The last bike I rode was a 1994 GSX-R750."

Cooley, for those too young to remember, made his name riding fierce Suzuki GS1000s built by the legendary Hideo "Pops" Yoshimura. In a profes sional career that spanned the decade 1976-85, Cooley was AMA Superbike Champion in 1979 and `80, winning eight nationals and twice topping the prestigious Suzuka 8-Hours endurance race.

Son of the man who ran Southern California's American Cycle Association, Cooley started roadracing early. His first race-he remembers the date, August 14, 1970-came at the tender age of 14, on a humble 200cc Greeves Silverstone. Cooley turned a best lap time of 2:30 that day at Willow Springs, but he advanced quickly, and a couple years later set a track record of 1:35 on a 250cc Yamaha. Today, Steve Rapp's track record stands at 1:19 and change.

Cooley's early performances attracted the attention of Yoshimura-the man, not the company-who was just starting to make a name for himself in the U.S. The pair went on to a successful eight-year relationship, first with Kawasaki and then Suzuki, first with the ACA and then, after the AMA Superbike class was born in 1976, on the national circuit.

That relationship dissolved when Suzuki pulled the plug on its Superbike effort prior to the start of the 1983 season-the year the four-cylinder displacement limit switched from 1025cc to 750cc-but Cooley landed a prime spot on the Gary Mathers/Rob Muzzy-led Kawasaki squad. Unfortunately, despite the fact that Cooley's teammate Wayne Rainey won the title, Kawasaki pulled out of road racing at the end of that year, leaving Cooley as a privateer for the first time in almost a decade.

Undeterred, he went on to post consistent top finish es in the AMA Superbike and Formula 1 series, and in 1985 very nearly won the Daytona 200 on a rented Team America Honda VF75OF. And then, while rac ing a Starfire Honda Superbike at Sears Point later that year, tragedy struck.

"I'd worked hard to get by Fred Merkel for the lead," recalls Cooley of that fateful day, "so naturally I was disappointed when the race got red-flagged. On the first lap of the restart, I crashed in Turn 1 at around 140 mph, and flew head-first into the wall. I never even touched the ground."

The crash very nearly killed Cooley, rendering him unconscious for 12 days. He awoke to discover the extent of his injuries, which included a broken neck, both femurs, a hip, a couple of fingers and various internal wounds. A get-well phone call from actor Paul Newman, whom Cooley had met at Willow Springs, came as little consolation.

Adding fuel to the fire, a sidecar passenger was killed in the very same spot the day after Cooley's accident, prompting the AMA to set up a speed-reduc ing chicane at the entrance to the corner that was used for the next 15 years. Thankfully, this past autumn Sears Point's new owners finally bulldozed the specta tor bridge and dirt embankment that Cooley hit, giving the corner some much-needed runoff.

Though Cooley raced on and off until 1991-most notably for Team Suzuki Endurance in the annual Willow Springs 24-Hour-that big crash effectively ended his career. So while many of his contempo raries, men like Rainey, Merkel, Eddie Lawson and Freddie Spencer, went on to lead rock-star lives with million-dollar gigs in the 500cc Grand Prix and World Superbike series, Cooley struggled to cope with life after racing. He got divorced, had a bout with drugs, moved in with his father in Oregon, and then met a woman, with whom he set up house in Twin Falls, Idaho, where he lives today. Cooley had taken a cou ple years of pre-med as a youngster, and he eventually went back to school, emerging as a registered nurse. Today, he helps rehabilitate patients after surgery. So in a way, he's giving something back to the medical profession that helped bring him back from the brink.

"I'm lucky even to be walking today," says Cooley, now 45. "And I'm even more fortunate, because although I broke 33 bones in my career, none of them bother me now."

Cooley certainly didn't seem to be affected by any nag ging injuries during our day together. He cheerfully posed for photos on pit lane, and then did a few warm-up laps on the GSX-R 1000 to blow out the cobwebs. Tom Sera's Fastrack Riders club was hosting a track day, and I gave Cooley the option of riding around the racetrack or going for a street ride. He chose the latter, and so we set off on a ioop into the nearby Tehachani Mountains.

It was unseasonably warm for autumn in the moun tains, so despite getting lost and nearly running out of gas, we had a very pleasant ride. We stopped occasional ly to trade bikes and chat, and in the evening adjourned to the Golden Cantina restaurant for margaritas and a debriefing session.

"I'd have to say that both of these streetbikes work better than anything I ever raced," Cooley began. "I think Pops' bikes made comparable power, but they had a narrow powerband and hit a lot harder. These bikes, particularly the-how do you say that?-the E-Iayabusa, make power every where. And they're incredibly smooth."

As impressed as Cooley was with the new bikes’ engine performance, however, he was even more blown away by their chassis.

“Bikes sure handle a lot better these days,” he declared. “Even the Hayabusa, as big as it is, steers really light and neutral. And they’re both so stable. I remember when Goodyear first made racing slicks back in the late ’70s, we couldn’t even use them. We put them on and the bike just wobbled; the frame couldn’t cope with the added traction. We had to go back to treaded tires. I don’t imagine that would be a problem with these bikes.

“The other thing is the brakes, and I think a lot of that has to do with the forks not flexing,” continued Cooley, who only raced with upside-down suspenders near the end of his career. “They were just bringing out four-piston brakes when I quit racing, so I never experienced six pistons until today. We used to play around with master-cylinder piston sizes, but we never got the light feel combined with the stopping power that these bikes have. It’s just incredible.” Cooley also offered insight into what it took to set up a racebike’s chassis in the days before fully adjustable everything. Forget about the comparably simple task of physically dismantling a set of forks or shocks (yes, two of them) to change damping or spring preload; sometimes, much more drastic measures were required.

“The year Graeme Crosby and I teamed up at Suzuka, the bike’s wheelbase was too long, so it wouldn’t turn,” Cooley recalled, “so the mechanics cut and re-welded the steering head and gas tank overnight, and we won.”

Cooley’s remarks weren’t all positive, however, as he had a few criticisms of the modem bikes. For one, while he was largely impressed by his first taste of fuel-injection, he noted that the Hayabusa’s throttle response was a bit abrupt at cracked-open throttle. Second, while he appreciated that the reach from the seat to the handlebars is much shorter nowadays, he didn’t care for the clip-on handlebars and low windscreen so obviously aimed at top-speed numbers instead of real-world rideability. “I grew up with high handlebars, which give you a lot of leverage,” Cooley said, adding that his shoulders got pretty sore after wrestling the Hayabusa down Caliente-Bodfish Road. “Also, those old handlebar-mounted fairings we had seemed to have better wind protection.” But by and large, Cooley marveled at the huge progress made since his departure from motorcycling, and said he was reconsidering his decision to give up the sport. “You know, I was purposely staying away from bikes, because I thought I’d try to go too fast, and if I got hurt again I’d never hear the end of it from my co-workers at the hospital,” he said. “But after today’s ride, I’m thinking I need to get a streetbike after all. Do they make any with high handlebars?”

If someday near Twin Falls, Idaho, you cross paths with a Suzuki Bandit rider wearing a Wes Cooley-signature Arai helmet, you might want to stop him for his autograph.

Just don’t forget to say thanks.