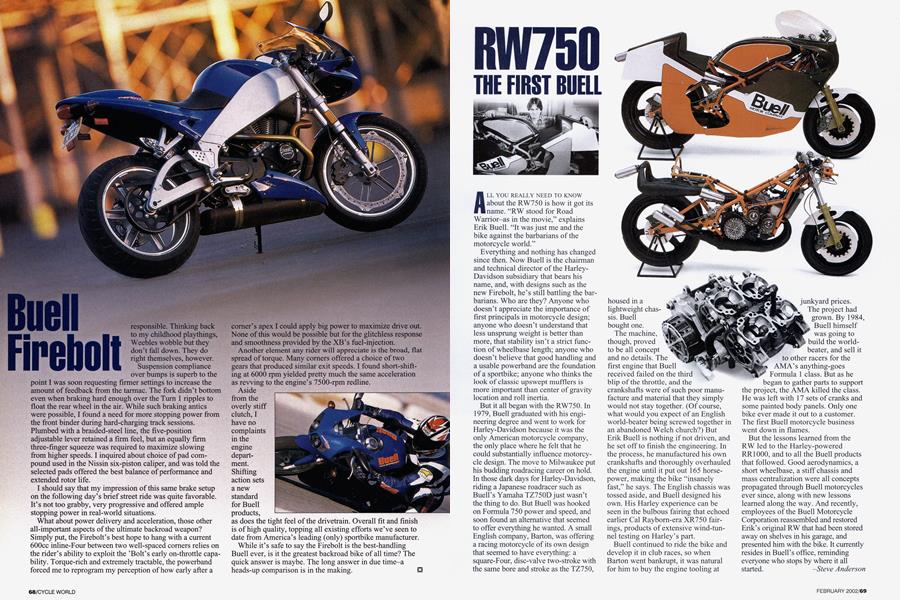

RW750 THE FIRST BUELL

ALL YOU REALLY NEED TO KNOW about the RW750 is how it got its name. "RW stood for Road Warrior-as in the movie," explains Erik Buell. "It was just me and the bike against the barbarians of the motorcycle world."

Everything and nothing has changed since then. Now Buell is the chairman and technical director of the HarleyDavidson subsidiary that bears his name, and, with designs such as the new Firebolt, he’s still battling the barbarians. Who are they? Anyone who doesn’t appreciate the importance of first principals in motorcycle design; anyone who doesn’t understand that less unsprung weight is better than more, that stability isn’t a strict function of wheelbase length; anyone who doesn’t believe that good handling and a usable powerband are the foundation of a sportbike; anyone who thinks the look of classic upswept mufflers is more important than center of gravity location and roll inertia.

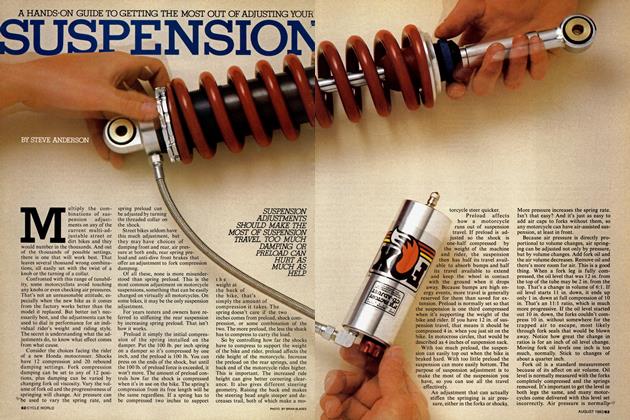

But it all began with the RW750. In 1979, Buell graduated with his engineering degree and went to work for Harley-Davidson because it was the only American motorcycle company, the only place where he felt that he could substantially influence motorcycle design. The move to Milwaukee put his budding roadracing career on hold. In those dark days for Harley-Davidson, riding a Japanese roadracer such as Buell’s Yamaha TZ750D just wasn’t the thing to do. But Buell was hooked on Formula 750 power and speed, and soon found an alternative that seemed to offer everything he wanted. A small English company, Barton, was offering a racing motorcycle of its own design that seemed to have everything: a square-Four, disc-valve two-stroke with the same bore and stroke as the TZ750, housed in a lightweight chassis. Buell bought one.

The machine, though, proved to be all concept and no details. The first engine that Buell received failed on the third blip of the throttle, and the crankshafts were of such poor manufacture and material that they simply would not stay together. (Of course, what would you expect of an English world-beater being screwed together in an abandoned Welch church?) But Erik Buell is nothing if not driven, and he set off to finish the engineering. In the process, he manufactured his own crankshafts and thoroughly overhauled the engine until it put out 165 horsepower, making the bike “insanely fast,” he says. The English chassis was tossed aside, and Buell designed his own. His Harley experience can be seen in the bulbous fairing that echoed earlier Cal Raybom-era XR750 fairings, products of extensive wind-tunnel testing on Harley’s part.

Buell continued to ride the bike and develop it in club races, so when Barton went bankrupt, it was natural for him to buy the engine tooling at

junkyard prices. The project had grown. By 1984, Buell himself was going to build the worldbeater, and sell it to other racers for the AMA’s anything-goes Formula 1 class. But as he began to gather parts to support the project, the AMA killed the class. He was left with 17 sets of cranks and some painted body panels. Only one bike ever made it out to a customer. The first Buell motorcycle business went down in flames.

But the lessons learned from the RW led to the Harley-powered RR1000, and to all the Buell products that followed. Good aerodynamics, a short wheelbase, a stiff chassis and mass centralization were all concepts propagated through Buell motorcycles ever since, along with new lessons learned along the way. And recently, employees of the Buell Motorcycle Corporation reassembled and restored Erik’s original RW that had been stored away on shelves in his garage, and presented him with the bike. It currently resides in Buell’s office, reminding everyone who stops by where it all started.

Steve Anderson