GEORGIAROCKET

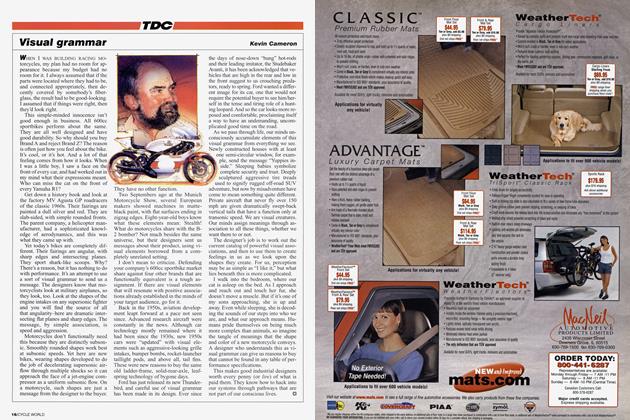

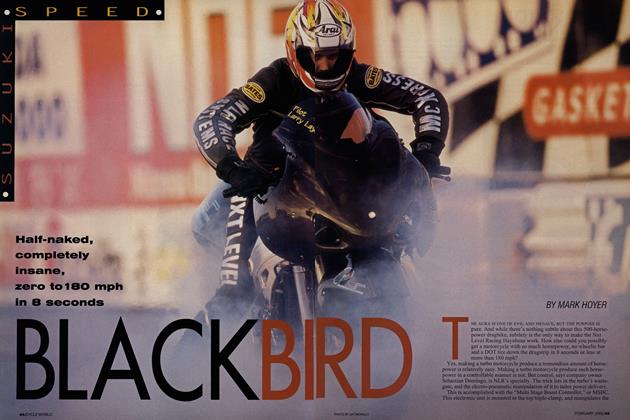

THINK TODAY’S KING streetbikes turn quick zero-to-60-mph times? Think again. Two-point-five seconds may sound impressive if you’re comparing a Suzuki GSXR1000 to a car, but it’s so far from a Pro Stock dragbike as to be embarrassing. A Pro Stocker catapults its rider to 60 mph in less than 60 feet and 1.1 seconds, pulling nearly 2.5 g’s in the process. Think F14 launched from the deck of a carrier via steam catapult, and you’re starting to wrap your head around the pure violence of a Pro Stock launch. By the time a Pro Stocker has covered the quarter-mile, just a tick more than 7 seconds has gone by, and it’s traveling 190 mph.

And there’s no better example of the breed than George Bryce’s Star Racing Suzuki, which Angelle Savoie piloted to the 2001 NHRA Pro Stock Championship. It represents the current peak of Pro Stock engineering and design.

As with all Pro Stock bikes, Bryce’s Suzuki is built to the NHRA’s strict set of rules. The idea is to provide close competition at a reasonable price while not getting into the kind of nuclear arms race that makes Top Fuel motorcycles so over the top that even talented and experienced racers often shy away from them. The rules are simple: Build a bike that looks a bit like a production streetbike-at least if you use a little imagination. Don’t stretch the wheelbase more than 70 inches, and put the wheelie-bar wheels a specific maximum distance behind the rear axle. Keep the rear slick to 10 inches in width. For an engine, use an approved set of engine cases, and feel free to bore and stroke it to the class limits. Those limits depend on engine configuration. For a four-valve-percylinder engine, don’t go beyond 1294cc; for a two-valve, don’t punch it out more than 92 cubic inches, or 1508cc. Finally, make sure it runs on gasoline, and don’t forget the fine print.

Bored with the acceleration of a Hayabusa or GSX-RI000? Star Racing's championship-winning Pro Stocker makes the average streetbike look about as quick as a rock

STEVE ANDERSON

Of course, if you’re Bryce, a man who’s been drag racing for a quarter of a century, the rules are just a challenge, an obstacle on the way to a true competitive advantage. The soft-spoken Georgian explains that he doesn’t want to break the rules, but he does “like to make them write new ones.” His Suzuki started life, as did most other Pro Stockers, built around a set of 1985 GS1150 cases. Those are stout enough, he explains, to take 400 horsepower. (Only problem is that Suzuki is running out of them, and the dies are worn-out.

The rules will soon have to be changed, says Bryce, to allow aftermarket cases.) Bryce also works with a two-valve cylinder head-originally from a GS1000, now a Ward Performance Vortex head with twin sparkplugs, a flatter valve angle and better ports than the Suzuki part. The displacement break for two-valve engines, Bryce says, is simply too great for anyone to seriously pursue the smaller four-valve alternative.

To take a Suzuki engine to 1508cc requires a new cylinder block with siamesed cylinders-no cooling air can slip through passages between the cylinders. But a drag engine, operating for a few seconds at a time, is essentially uncooled; it simply doesn’t run long enough to come to an equilibrium temperature, and instead of a radiator or air, relies on the heat capacity of its own structure to absorb a single run’s waste heat. Wiseco pistons fill the 85mm bores, while a special Falicon crank with custom flywheels bumps the stroke to 66.4mm, just enough to reach the displacement limit. Most other teams running Suzukis don’t bother with this last tweak, giving up 20-some-cubic centimeters in order to run stock Suzuki flywheels. Bryce, though, figures the extra expense is worth the single extra horsepower, because it translates into a 0.01-second quicker quarter.

The Vortex head breathes through four 48mm Lectron carbs and huge 1.85-inch intake valves. That’s all the more impressive when you realize that this engine turns to almost

14.000 rpm. And that’s despite savage Cam Motion camshafts that make those used in AMA Superbikes look tame. How does the engine hold together at those speeds? Mostly because its high-rpm operation is measured in a few seconds, perhaps 12 at most per pass, including the pre-run burnout and the run itself. Twelve seconds at an average of

13.000 rpm translates into 2600 complete revolutions, only 1300 firing impulses for each cylinder-well into the range where high-cycle fatigue failure isn’t an issue. And the engine that begins an NHRA national isn’t likely the one Bryce has in it for the final round. Accordingly, a drag engine can simply be used a lot harder, the valve springs made stiffer, the parts worked closer to the edge than with an engine for other, more-endurance-oriented racing.

Currently, Bryce’s best engines are pumping out 305 horsepower at 12,600 rpm-or 36 bhp more than three years ago. “We’ve been adding a horsepower a month,” he says. About the time he spends every week doing engine development on the dyno, Bryce says, “That’s my job: to find more power, and make it go faster.” Some of that power comes from things that have external clues, such as the new cylinder head. Others give no hint, such as the mere 1 '/2 quarts of less-than0-wt synthetic oil that lubricates the engine and transmission.

Of course, making the power is just half the job-the rest is using it most effectively to push the bike down the track. In that, Bryce has a real advantage in his rider.

Not only is Angelle Savoie talented, driven and consistent, she also weighs just 110 pounds. While Pro Stock rules dictate that every bike/rider combo must weigh a minimum of 600 pounds, there’s a real advantage in having a 450-pound bike with a 110-pound rider and 40 pounds of ballast, instead of a 450-pound bike with a 150-pound rider.

In the former case, you can ensure that the center of gravity is lower by positioning the ballast low and close to the front wheel. And Bryce’s bike carries more than 20 pounds of depleted uranium ballast (heavier than lead) as close to the bottom edge of the front wheel as it will go. There used to be more, but the Star Racing Suzuki now carries no fewer than three electrically driven vacuum pumps to evacuate the crankcase. By pulling more than 25 inches of crankcase vacuum, Bryce picked up more than 10 bhp, and his competitors can’t afford the weight of three pumps. Bryce points out that two of the three vacuum pumps are mounted high, because that was the only place to put them. “It reduces our center of gravity advantage,” he says. “It’s as if we had a 135-pound rider instead of a 110-pound one.”

Once again, Bryce

has succeeded in getting the rules rewritten. Next year, the NHRA will allow only a single pump.

But perhaps Bryce’s biggest edge is his long experience using telemetry to tell him exactly what the big Suzuki is doing down the track. He started using electronics to monitor bike behavior back in 1984, and now multiple sensors and a “black box” record every detail of the Suzuki’s ontrack performance, from rear-wheel spin and clutch slip to air-fuel ratio for each cylinder and engine rpm. After each run, Bryce downloads the data, and he and his crew change the bike’s setup accordingly. Some of that may be as simple as gearing changes, but most important is the set up of the centrifugally assisted clutch. The Star Racing machine uses stock Suzuki clutch plates and springs, but operated through an MTC multi-stage lock-up.

This type of mechanism takes the control of clutch slip away from the rider (he or she just drops the clutch lever off the line), and places it instead in the hands of the crew chief. The mechanism has to be tuned to produce just the results desired. In this, Bryce has been particularly innovative. Formerly in Pro Stock, according to competitor Steve Johnson, riders would launch at 8500 to 9000 rpm, with the clutch set up to slip enough that the rear tire wouldn’t spin. Bryce and Savoie have come up with a different strategy, with Savoie launching at 10,000 to 10,500 rpm, and Bryce setting up the clutch to strike a balance

between slip and controlled tire spin off the line. According to Johnson, that strategy appears to produce a more consistent launch, and is being copied by some other riders.

Despite having just won the 2001 championship, Bryce is ready to retire his Suzuki. “It’s four years old,” he says. “When we debuted it, it was revolutionary. The engine was so far forward that we had to run a custom header, something that other people weren’t doing then. Back then, it was a showpiece. But we’ve kept adding stuff to it, and now it looks like a duct-taped scab.”

Bryce quickly gets excited talking about the new bike. It will use the current engine, but with another winter of development. It will be designed to carry the engine even farther forward, he says, “because you can’t get it too far forward.” If the NHRA won’t let him run three vacuum pumps, he’ll run one so big that it’ll be just as effective. The chassis will be designed around that pump, which will sit as low as it can possibly go. Bryce positively radiates while talking about this. He wants to sign Savoie to another three-year contract, and win more championships. After placing his bike first or second in NHRA Pro Stock for the last 12 years straight, don’t bet against him.