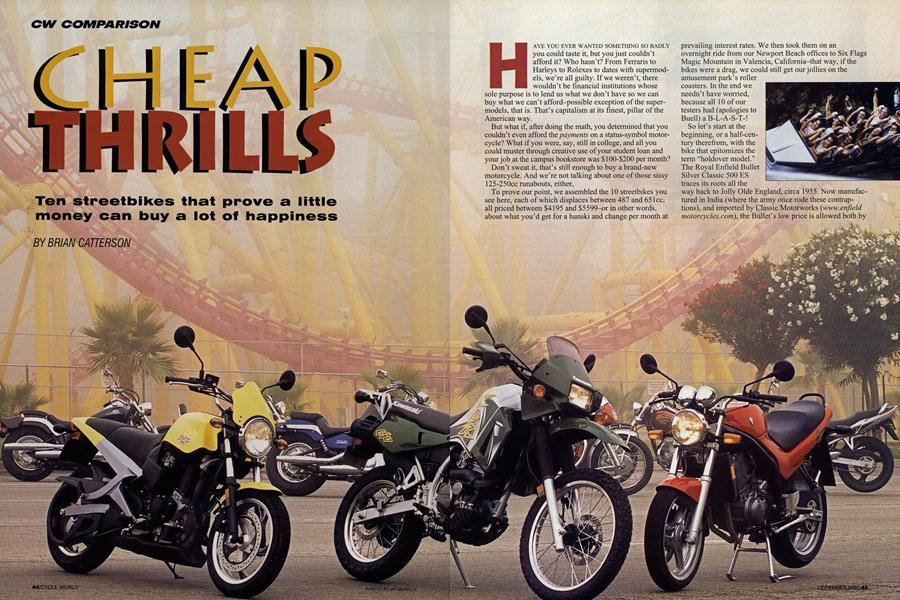

CHEAP THRILLS

CW COMPARISON

Ten streetbikes that prove a little money can buy a lot of happiness

BRIAN CATTERSON

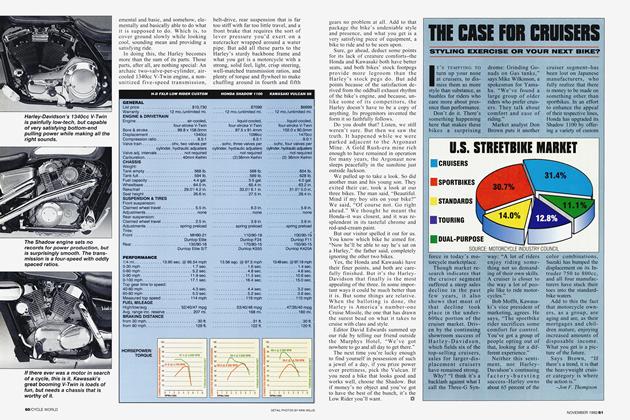

HAVE YOU EVER WANTED SOMETHING SO BADLY you could taste it, but you just couldn’t afford it? Who hasn’t? From Ferraris to Harleys to Rolexes to dates with supermodels, we’re all guilty. If we weren’t, there wouldn’t be financial institutions whose sole purpose is to lend us what we don’t have so we can buy what we can’t afford-possible exception of the super-models, that is. That’s capitalism at its finest, pillar of the American way.

But what if, after doing the math, you determined that you couldn’t even afford the payments on a status-symbol motorcycle? What if you were, say, still in college, and all you could muster through creative use of your student loan and your job at the campus bookstore was $100-$200 per month?

Don’t sweat it, that’s still enough to buy a brand-new motorcycle. And we’re not talking about one of those sissy 125-250cc runabouts, either,

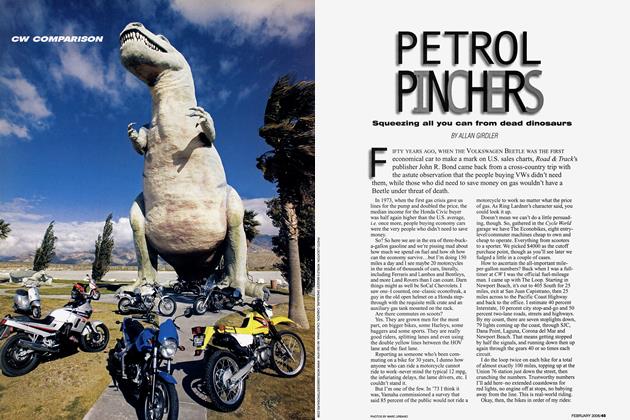

To prove our point, we assembled the 10 streetbikes you see here, each of which displaces between 487 and 651cc, all priced between $4195 and $5599-or in other words, about what you’d get for a hunski and change per month at prevailing interest rates. We then took them on an overnight ride from our Newport Beach offices to Six Flags Magic Mountain in Valencia, Califomia-that way, if the bikes were a drag, we could still get our jollies on the amusement park’s roller coasters. In the end we needn’t have worried, because all 10 of our testers had (apologies to Buell) a B-L-A-S-T-! So let’s start at the beginning, or a half-century therefrom, with the bike that epitomizes the term “holdover model.” The Royal Enfield Bullet Silver Classic 500 ES traces its roots all the way back to Jolly Olde England, circa 1955. Now manufactured in India (where the army once rode these contraptions), and imported by Classic Motorworks (www.enfield motorcycles.com), the Bullet’s low price is allowed both by a favorable exchange rate with the Indian rupee and the fact that the tooling was paid for back when Queen Elizabeth was a babe. If ever that were the case. Judged purely in terms of performance, the Bullet’s moniker couldn’t be more malapropos, its air-cooled, two-valve, pushrod, 499cc Single delivering a wheezing 16 horsepower to the 19-inch rear Avon Speedmaster. Moreover, its drum brakes work only slightly better than Fred Flintstone’s feet, and the odds of finding a gear in the four-speed tranny on the first attempt are about as likely as hitting the jackpot at Las Vegas.

But to judge the Enfield purely in terms of its performance is to miss the point entirely, because what the Bullet is, is an instant classic-a vintage bike without the hassle of restoration. To a man, every one of our testers who sat in the Enfield’s bicycle-like sprung saddle found himself laughing out loud inside his helmet, not at the bike but with it.

HONDA VLX DELUXE

$5299

KAWASAKI KLR650

$4999

We all want one, just not for a daily rider.

One spot higher up on the Singles hit parade is the Buell Blast, probably the most trumpeted entry-level bike since the 1985 Honda Rebel. Made by cleverly lopping one lung off a Harley-Davidson Sportster, the Blast’s air-cooled, twovalve, pushrod, 492cc Single is smooth by Thumper standards, and despite making just 27 horsepower comfortably propels the bike at freeway speeds and beyond. No less clever is the Blast’s riding position, sort of a half-step between a standard and a cruiser with slightly forward-set footpegs, narrow high-rise handlebars and a pillow of a seat that one tester suggested, “feels like it’s stuffed with Wonderbread.”

The thing about the Blast is it’s tiny, toy-like even, which would be great for 5-footers except for the fact that the fat fuel tank and the ungainly footpeg hangers splay the rider’s legs at a standstill, making the seat feel higher than it is. Our testers also panned crude details such as the belt pulley that’s almost as big as the rear wheel (and twice as wide as the drive belt), the bizarre styling and Blammo! comic-strip graphics.

If the Blast were a downsized version of the XB9S Lightning tested elsewhere in this issue, Buell would have a winner on its hands. Better yet, Harley’s product planners should put the Blast’s motor in a mini-Sportster; they could call it a Sprint to maintain a tenuous tie with history. And probably sell a bazillion of the things.

Perhaps one reason Harley didn’t build a single-cylinder Sportster is because Suzuki already has. Viewed from a distance, the menacingly named LS650 Savage certainly looks like a Vee-minus-one. It isn’t until you get up close to it that you realize it’s 2/3 scale, roughly the same size as the Blast. And then the chuckles about the name begin, because this thing is as savage as a Shih-Tzu!

Like the Blast, the “new-for-1986” Savage is tiny and toy-like; taller riders can’t help feeling like Shriners as the handlebars hit their knees at full-lock. But the Suzuki’s feet-forward riding position is comfortable for shorter folks. And thanks to the narrow fuel tank and seat, flat-footing it at stoplights is easy for everyone. If you stand around 5-feet-tall, the Savage is the only real alternative to a 250cc cruiser.

Fit and finish are a cut above that of the Buell, as is engine performance from the air-cooled, four-valve, sohc, 652cc Single, owing mostly to its greater torque output. Like the other three cruisers in this group, the little Suzuki is equipped with 19-inch front and 15-inch rear wire-spoke wheels, single-disc front and drum rear brake. Yet in spite of these apparent cost-cutting measures, the Savage works very well for a bike at this price point. “The only thing lacking is a raccoon tail hanging from the sissybar,” chuckled one tester.

KAWASAKI NINJA 500R

$5099

KAWASAKI VULCAN 500 LTD

$4699

MZ SKORPION TOUR

$4995

Moving onto the twin-cylinder cruisers, we’ll first check in on the Kawasaki Vulcan 500 LTD. Growing out of the 454 LTD that debuted in 1985, and first available in 1991, the Vulcan is powered by the same basic liquid-cooled, fourvalve-per-cylinder, dohc, 498cc parallel-Twin as the sporty Ninja 500R. It’s just tuned differently, with smaller carburetors that boost midrange power at the expense of top end.

Not that the Kawasaki doesn’t have top end, mind you, because compared to the two V-Twin cruisers in this comparo, it’s a re wer, with the most peak horsepower and an exhaust note that one tester termed, “Porsche-ish.” Further aided by a slick-shifting six-speed gearbox, the Vulcan posted the hottest quarter-mile time of the feet-forward brigade, nearly a full second quicker than the Yamaha and another two-tenths quicker than the Honda. If ever a bike with 40 horsepower could be called a “power cruiser,” this is it.

But while the Vulcan’s engine is a hoot, we can’t help feeling that it’s misplaced, both functionally and visually. The bike as a whole is nicely styled, all of its design elements working in simpático, until you get to the two cylinders, which jut straight up from the crankcase, leaving all sorts of empty space in front and behind. A V-Twin would just fit better.

As it does on the Honda VLX. One of those “invisible” models that sell in the thousands despite little fanfare, the VLX is now in its 15th season, unchanged except for minor restyling.

Like virtually every other Honda, the VLX has that “justright” feel. The seating position is very natural, and the bike is nicely appointed, with warning lights attractively inset in the top triple-clamp, machined-aluminum footpegs, a Harley Softail-style rear end and staggered dual

exhausts that look much more appropriate than the Vulcan’s one-on-each-side treatment.

The unsightly gap between the tank and the plush king/queen seat was actually intended, as that was the sort of thing they did on Frisco-style choppers back in the ’70s.

Though liquid-cooled, the VLX’s sohc, three-valve-per-cylinder, 583cc V-Twin has cylinder fins that suggest it’s air-cooled, and as on the Vulcan the radiator is hidden from view between the frame downtubes.

As nice as the VLX is, it was routinely damned with faint praise, owing mostly to its mediocre engine performance. The 52-degree V-Twin’s Harley-style single-crankpin engine makes all the right potato-potato sounds, but it’s the slowest of the Twins tested here. Hindered by its four-speed gearbox, it tied with the single-cylinder Suzuki Savage over the quarter-mile. Ouch!

Yamaha’s V-Star Custom, on the other hand, garnered mostly rave reviews. First offered in 1998, the V-Star grew out of the 535 Virago that debuted in 1987.

Like the American V-Twin it’s meant to emulate, the VStar’s two-valve-per-cylinder, 649cc, 70-degree V-Twin is air-cooled, though it makes use of single overhead cams in lieu of more “authentic” pushrods. Engine performance is much healthier than the numbers indicate, particularly through the midrange, and power is transmitted to the fat rear tire via a five-speed gearbox and shaft drive.

While in many ways the V-Star reminded testers of the VLX, it simply feels more substantial, like a boulevard bike should. This is at least partly attributable to the seating position, which splays your legs wide around a fat fuel tank to forward-set highway pegs, your hands reaching outward to grasp buckhom handlebars. “Nice and solid,” wrote one tester in his notes.

Criticisms were limited to a narrow range of clutch engagement, pitiful cornering clearance (even by cruiser standards) and a Softail-style rear suspension that bottomed too easily. But aside from that, the consensus was universally positive, earning the V-Star “Best Cheap Cruiser” honors.

“Best Cheap Dual-Purpose Bike” was no contest, as the Kawasaki KLR650 was the only entry with any off-road pretensions. Debuting as a 600 in 1984, and growing to 651cc in 1987, the KLR was an instant hit, earning legions of fans who praised its go-anywhere character and versatility.

Fifteen years later, only the paint scheme has changed, our testbike’s green-and-brown camouflage playing up the KLR’s role (converted to run on diesel!) in the U.S. military. And it’s just as tall ever: If you stand under 5-foot-9, this is not the bike for you, its 36-inch-high seat instilling airsickness in shorter pilots.

ROYAL ENFIELD BULLET 500 ES

$4195

SUZUKI LS650 SAVAGE

$4299

Though the big, four-valve, dohc Single bucks and lurches when you lug it down to a crawl, it mellows out at higher rpm, and is actually quite smooth at supra-legal freeway speeds. The frame-mounted bikini fairing does an admirable job of deflecting the windblast, and the 6.1-gallon fuel tank coupled with the mother of all luggage racks goad you into going for extended rides. As one tester put it, “If I had to ride one of these bikes from California to New York tomorrow, the KLR would be it.” Though the KLR is a thoroughly capable adventure-tourer, it also does a decent impression of a sportbike. When the going got fast, the Kawasaki got going, one of the four motorcycles in this group that set the pace on twisty backroads. Only when pushed to the limit does the narrow 21-inch front tire result in slightly sketchy handling. But you have to be going at a pretty good clip to notice that. A clip set by, say, the MZ Skorpion Tour.

Made in what used to be called East Germany, and imported by Motorrad of North America (www.motorradna.com), the Tour is a stripped-down version of the racy Skorpion Sport Cup, with a wide, swept-back tubular handlebar in lieu of the latter’s clip-ons.

As such, it’s a sporty-feeling bike, its liquid-cooled, twin-carb, five-valve, sohe Yamaha Single (sourced from the Euro-only XTZ660) boasting the most torque and the second most horsepower of this group. Tall gearing hinders acceleration off the line, but once up to speed the Skorpion is an absolute riot, its capable Paioli fork, Bilstein shock and Metzeier MEZ1 tires letting it get the most out of a twisty road. On our way home we rode over the legendary Angeles Crest Highway, and the MZ ran right up there with the front-runners.

Functionally, the only gripes we had concerned the flimsy shift shaft, which made for somewhat sloppy shifting, and the slightly grabby Grimeca four-piston front disc brake.

SUZUKI GSSOOE

$4399

YAMAHA V-STAR CUSTOM

$5599

Cosmetically, however, we had a few additional complaints, such as the tacked-on evaporative fuel recovery canister required by the California Air Resources Board (then again, most of the other bikes were 49-state models), and overgrown muffler and rear mudguard. But the nickelplated sideand centerstands are a nice touch-strange the latter comes standard on a cheap bike when it’s absent on so many more expensive motorcycles.

Adding a cylinder brings us to the Kawasaki Ninja 500R. Ultimate evolution of the EX500 that debuted in 1987, the Ninja had its wheels and brakes upgraded in ’94, but is otherwise mechanically unchanged.

First impression is that the Kawasaki is quite small, hardly any bigger than its 250cc sibling. That’s great for shorter riders longing for a proper middleweight sportbike, but bad for taller riders who’ll feel cramped by the tight seat-to-peg relationship and narrow handlebars. Everyone appreciates the frame-mounted half-fairing, though, which does a superb job of keeping wind, rain and suicidal bugs off of your riding togs.

Next impression is that the Ninja’s twin-cylinder engine (hot-rodded from more pedestrian Vulcan trim) is potent, standing head and shoulders above every other bike in this test. With 52 horsepower arriving at the rear wheel, the Kawi makes 7 more horspower than the MZ, and sprints through the quarter-mile 1.4 seconds quicker.

It handles well, too, with nice, light steering and ample cornering clearance. It’s only when you’ve got the Ninja heeled way over in a bumpy comer that it starts to show its age, the square-tube steel frame and dated suspension allowing a fair amount of tire chatter.

You won’t get any of that with the final contender in this comparison, the Suzuki GS500E. In a word, this thing is sweet, with handling more akin to that of a modem sportbike than any of the other “cheapskates” tested here.

While the twin-spar frame looks like the product of GSX-R technology, it’s really steel painted silver to resemble aluminum. But it’s still hell-for-stout, making for a chassis whose only shortcoming is a too-soft fork that bottoms when you grab a handful of the superb Tokico two-piston front disc brake.

Unlike with many of the other bikes in this test, everyone found the GS500 comfortable, its superbike-bend tubular handlebar, moderately rearset footpegs and plush saddle welcoming riders short and tall. Last year, the GS received a new seat, tank, tailsection and more modem instmments, so that it now resembles a mini-Bandit; give it a fairing and the illusion would be complete!

A few testers remarked that they had trouble taking off from a standstill, a side-effect of the engine’s wimpy torque output (only the Enfield is weaker), which means you have to rev it to 7000 rpm and slip the clutch to get going. This trait is exacerbated when the engine is cold, because the lean jetting required for an air-cooled motor to pass modem emissions standards means the GS takes forever to warm up. A jet kit works wonders.

Considering that the Suzuki’s two-valve-per-cylinder, dohe parallel-Twin harks back to the 1978 GS400, we’ll excuse it for making “just” 41 horsepower-but only because it ran neckand-neck with the KLR650 for third-place dragstrip honors!

When our ride had ended and the results were tabulated, the Ninja 500R and GS500E topped everyone’s list of favorites. Which bike was the best overall, though, was a tough call; one pundit suggested that with the new Kawasaki/Suzuki alliance, a marriage of the former’s hotrod engine and the latter’s sweet-handling chassis would yield the ultimate cheap bike! Meanwhile, we’ll give the nod to the GS500E on the grounds of its $700 lower price tag.

Really though, motorcycling is the winner. Because when all was said and done, we had way more fun riding these $5000 two-wheelers than we did riding the roller coasters. And with amusement park tickets costing $42 for a single evening’s entertainment, the bikes are a better deal, too. You can take that to the bank. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontBeginner's Luck

December 2002 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Thousand Mile Ride

December 2002 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCFlexi-Flyers

December 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

December 2002 -

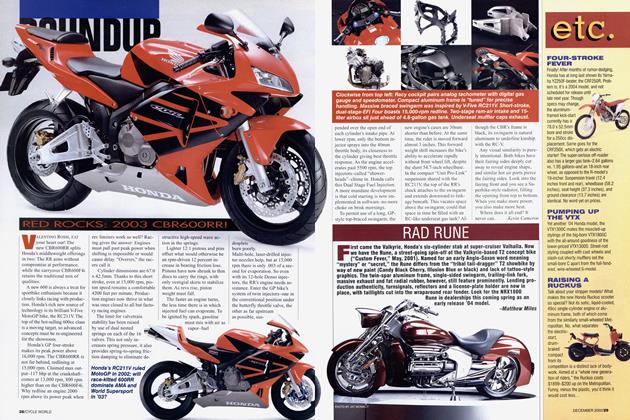

Roundup

RoundupRed Rocks: 2003 Cbr600rr!

December 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

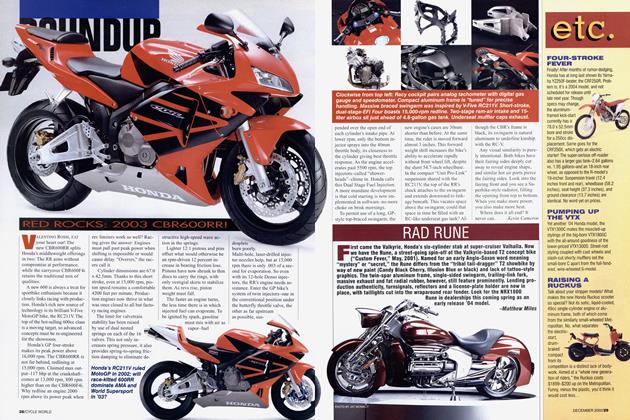

Roundup

RoundupRad Rume

December 2002 By Matthew Miles