Chop Shop

Billy Lane and his Magnificent, Mind-Frying Machines

KEVIN CAMERON

HOW CAN YOU USE YOUR OWN IDEAS TO DESIGN AND build motorcycles? Go to engineering or design school, then find a job with a big bike-maker? Where? Then, years of apprentice work, sharpening other people’s pencils and executing their ideas before you get to express your own? And once you’ve struggled to the top (assuming you do), what ideas you have left become subject to decision by committee and death by focus group?

What if you can’t stand it? What if your energy has to bum right now, while it’s hot, not be put off forever? Jump to where originality is always in demand. That place is custom bikes.

When sportbike riders think of customs, many scoff (as I have done), pointing to lack of brakes, suspension and handling. Stop. Take another perspective. How many sportbikes are ridden hard enough to test their capabilities? Versus how many of them cmise urban boulevards, 5000 rpm below the power, carrying shirtless persons in beach clogs? Let’s admit that bikes, despite the technologies they embody for objective tasks such as racing, touring or crosscountry, are also an expression of each rider’s inner aesthetic. Something in a particular bike or style sets our interior bells ringing even if we are not Daytona banking-bound or Paris-Dakar heroes. Part of our lives is real, external and visible. Another part is interior and unseen. Both are valid.

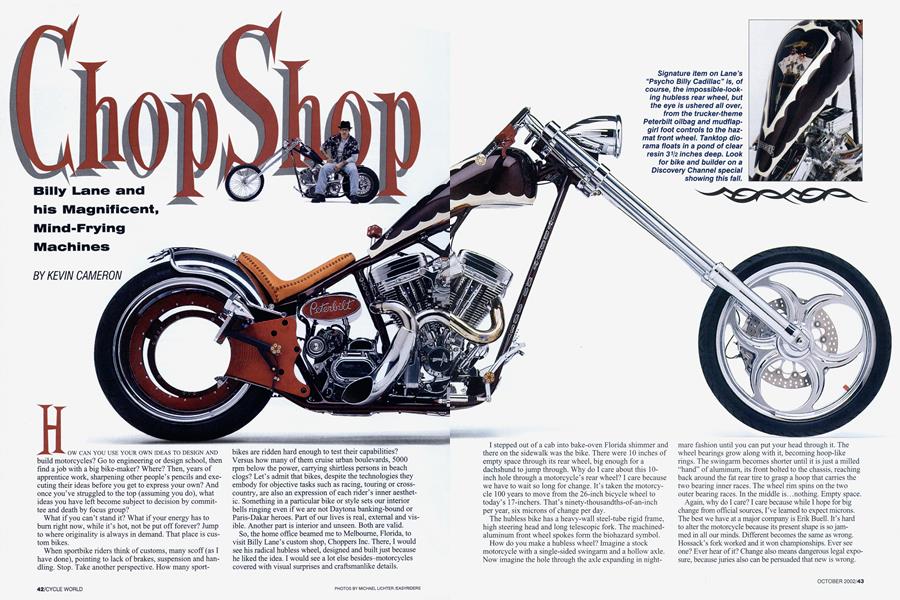

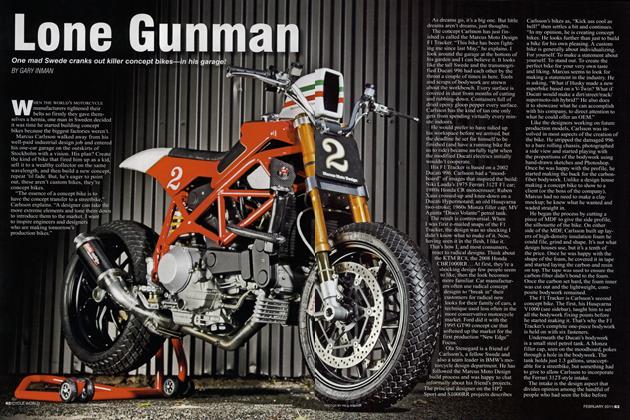

So, the home office beamed me to Melbourne, Florida, to visit Billy Lane’s custom shop, Choppers Inc. There, I would see his radical hubless wheel, designed and built just because he liked the idea. I would see a lot else besides-motorcycles covered with visual surprises and craftsmanlike details.

I stepped out of a cab into bake-oven Florida shimmer and there on the sidewalk was the bike. There were 10 inches of empty space through its rear wheel, big enough for a dachshund to jump through. Why do I care about this 10inch hole through a motorcycle’s rear wheel? I care because we have to wait so long for change. It’s taken the motorcycle 100 years to move from the 26-inch bicycle wheel to today’s 17-inchers. That’s ninety-thousandths-of-an-inch per year, six microns of change per day.

The hubless bike has a heavy-wall steel-tube rigid frame, high steering head and long telescopic fork. The machinedaluminum front wheel spokes form the biohazard symbol.

How do you make a hubless wheel? Imagine a stock motorcycle with a single-sided swingarm and a hollow axle. Now imagine the hole through the axle expanding in nightmare fashion until you can put your head through it. The wheel bearings grow along with it, becoming hoop-like rings. The swingarm becomes shorter until it is just a milled “hand” of aluminum, its front bolted to the chassis, reaching back around the fat rear tire to grasp a hoop that carries the two bearing inner races. The wheel rim spins on the two outer bearing races. In the middle is.. .nothing. Empty space.

Again, why do I care? I care because while I hope for big change from official sources, I’ve learned to expect microns. The best we have at a major company is Erik Buell. It’s hard to alter the motorcycle because its present shape is so jammed in all our minds. Different becomes the same as wrong. Hossack’s fork worked and it won championships. Ever see one? Ever hear of it? Change also means dangerous legal exposure, because juries also can be persuaded that new is wrong.

Billy Lane is the “Illustrated Man,” tattooed everywhere you can see. Every finger wears a silver ring, some set with turquoise. He radiates energy, acting through principles he is still discovering. His business is expanding rapidly-exploding,” he says. The walls of his shop are covered with posters of Brando, De Niro, James Dean, Marilyn Monroe. There are huge blow-ups of foreign and domestic magazine covers featuring his customs. Five bikes are on build-stands, although he says, “I’m getting out of complete bikes-takes too much time.” On the floor up front is a polished case from a GM 6-71 supercharger, the kind that sat atop so many Top Fuel Hemi Chryslers. The hot-rod era interests Lane. Every shape that bears meaning interests him.

Everything comes from the mind. There are no drawings here, no computers with “Build-a-Chopper” pull-down menus, featuring parts you’ve seen in every catalog. Custom means custom.

Here is a red bike whose Panhead Harley engine has its top-end off. Up front is a leaf-sprung Indian trailing-link fork. Lane turns the engine through, feeling and looking at the cylinder walls. He explains how an O-ring gets lost from this carb type, causing the idle system to pull up extra fuel. Cylinder-wall washing causes overheating, making the owner think he needs to retard the spark. Problems multiply. Now mechanic Nick Fredella is putting it back together. Part of an early Ford grille is smoothly let into the top of the hand-formed gas tank. Under the grille of “Devil in a Red Dress,” is one of the pinup logo-girls of Choppers Inc. The engine’s CNC-carved valve covers bear big basrelief images of tumbling dice.

The primary drive on this bike comes from Harley Top Fuel-a wide expanse of rubber tooth-belt that, when running, makes a speeding miniature exercise treadmill. Top Fuel-style exhaust pipes snake untraditionally to the left, curving down to dive between the runs of the belt.

Their upswept ends are capped by big rig-style metal flappers. When the engine starts, they flip and clatter with every cylinder firing, metal talking mouths.

The pipes are welded from smooth mandrel-bent sections, the welds smoothed to invisibility.

In the line to the S&S carb is a glass fuel sight bowl, like the ones that graced every auto and truck in the 1930s.

I begin to notice more little things, like the subtle flare of the bottom edges of the tank, and I want to know how it was made.

“Do you have an English wheel?”

“No, but I will,” Lane responds.

“How are these shapes made, then?”

“It’s all TIG, ground smooth.”

I thought about that. And I look around at other bikes, at details. Shorty rear fenders join tube frames in smooth, flowing transitions. All weld? Yes. Bondo Bob doesn’t live here. Fluid metal lives here. The curvature of the fender matches tire curvature perfectly, with a constant gap. Stand behind the bike and the side-to-side curvature matches the

tire, too. There are no sheetmetal edges.

“That’s rod-edging,” he says, picking up a half-inch steel rod. “I tack this onto the frame, close to the edge of the fender. Then I angle the TIG torch so it’s mostly heating the rod, and doesn’t bum a hole through the thin fender. The rod gets soft and you can just lay it down where you want it. Then you can blend it in with filler rod. When you’re done, the fender is strong.”

Sounds easy. Easy like learning to fly helicopters by correspondence course: “First, pull up to a hover.” Easier said. There are three welding machines here.

He and friend Claudia Irvine sit on a blue bike, checking the fit. “Seat’s just big enough for where you sit,” he says of the rider’s neat little leather-upholstered pad. Claudia, perched on the fender, reaches back to see how close she is to major rug-bum from the tire, millimeters away. “Go ahead, I give it my stamp of approval,” she says.

Metal control is the name of Lane’s work. His tubing bends are not simple curves; instead bend-radius changes smoothly along the curve. Serious force is required-this is Vs-inch-wall tubing. But that’s what it takes to contain the shaking engine and handle the moment on those tall steering-heads.

“I had to bum up 80 or 100 feet of tube to learn to do this,” he says of his “creep-bending” technique-pulling the tubing through the bender slightly between each application of force.

Other details. Lane holds four patents on his “six-gun” terminations for bar risers, footpegs, oil-tank caps, etc. The ends of these look just like a loaded cylinder from a .44 Magnum revolver. What appear to be real cartridge bases are just that, primers deactivated and cases cut off, then pressed into sized holes. Patents require big-time effort and money.

Lane cmises garage sales and swapmeets, looking for old objects that contrast with the present, carry some association or strike some blink of meaning. The shift knob on the red bike is a well-worn chrome-on-brass faucet knob. It carries a porcelain insert, reading HOT. Another bike’s tank has a 1940s-style spotlight emerging from its left side, with the handle on the right. Could have come straight off of my uncle’s ’48 Buick.

Lane says he hates two things: cheap and ugly. Ugly can be as simple as two curvatures that almost match. It can be a frame rail, angled to hit a rider’s thigh-anything that “doesn’t work” or makes a bike impractical to ride. Or ugly can be big. A lot of customs, in his opinion, are just too big-jumbo tanks, oversized seats. He likes clean and he likes small, with good real-world performance.

“I don’t do engines,” he says. “If I did, I wouldn’t have time for anything else. As long as the power is good, the bike will run strong if it’s light enough.” Like the bob-jobs of old, these bikes carry nothing extra-just an engine, two wheels and a place to sit.

In the search for “clean,” Lane has hidden the rear-axle adjusters and axle thrust screws inside the junction of frame tubes at each axle end. All is organic smoothness. In a variation, the red bike has a fixed-wheelbase belt drive, no adjusters. The axle ends in big wingnuts. Batteries are hidden inside oil tanks. Wiring and tubing is routed within frame tubes, emerging only where they terminate.

You don’t sit on these bikes. You sit down in them, below the engine’s cylinder heads, on the red bike your left leg arching over the rushing primary belt and the click-clacking pipes. Part of the game is to bring back a past world in which moving parts were seen in motion and black boxes were imaginary.

I ask him what percentage of total weight is engine. He considers a moment.

“About 50.”

That’s the same percentage as on roadrace bikes-same intention, different paradigm.

Customer work goes on all day, but Lane has been thinking about something for a while. At night the paying work is finished and he decides to cut metal on his next project. Nobody is tired. “Late at night, with the music turned up loud” is when things happen here. Up above, hanging from the ceiling, are empty Chianti bottles, memorials of long evenings when the shop floor is covered with tools until the sun comes up and the project rolls. An Everlast heavy bag gantries from a ceiling post. Young men, making energy.

Foot controls are devil’s tails-tapered bars heat-bent, with arrow points. Taillights are CNC-milled from aluminum, red dice illuminated by pointed bulb-holders. The top of the gas tank on the hubless bike is a sunken diorama of clear resin containing dice, a Derringer, four aces and a tattoo needle.

The phone rings. I can hear Jesse Sparks at the order desk answer laconically, “Choppers...” All day, parcel shippers come and go, carrying away product.

Lane’s first products were wheels, when the tire manufacturers began to make really wide rubber, 200s and bigger from Metzeler, Pirelli and Michelin. He went to junkyards to find auto or truck rims the right size, cut the centers out, and dimpled and drilled them for spokes. The result is like a sportbike tire, but carried to an extreme. He likes big, inside-out brakes, but was told they couldn’t work with spoked wheels. He uses Braking USA perimeter discs, mounted as floaters to the rim with little heartshaped clips.

When he began to think about a hubless wheel, he had never heard of Swiss designer Sbarro’s similar concept. He just liked the idea. Then he had to find big, speed-qualified

bearings. He did. These are 12 x 14 x 1-inch angular-contact specials with half-inch

balls and machined bronze separators, made for a helicopter gearbox.

They’re $2500 apiece and he had to devise and make his own seals. Now he’s planning a hubless Softtail-style design, but with a bigger

hole through it, 14 inches. The current bike is driven by a toothbelt, but maybe he’d like to explore something else next time, some kind of invisible drive, another shock to the eye’s expectation. He’s thinking about it. Meanwhile, this bike is a runner, not a showpiece stuck in angel hair. He’s ridden it as fast

as it will go, maybe 130 mph. It works.

mph.

What comes next? Creativity becomes livelihood

only by selling

pieces of it to thousands of people. But that sale turns today’s sensation into tomorrow’s cliché. Can Billy Lane be the endless fountain of fresh sensations? He says the trick is to pull back, out of manufacturing and distribution, leaving them to people who know how to make money at them, saving his energy for design.

Even so, the creativity game is like crossing Lake Ontario by snowmobile in summer. Keep the speed up just right-fast enough to plane, slow enough to get where you’re going.

I hated to leave because in this place I felt I’d found people more likely to explore big changes in the shape of the motorcycle than any in industry or in racing. People willing to risk the leap to the next thing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontI, Ducatista

October 2002 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Tale of Two Suzukis

October 2002 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCY-Alloy? Why Not?

October 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

October 2002 -

Roundup

RoundupCruising In Luxury: Bmw R1200cl

October 2002 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupCentennial Harleys

October 2002 By Matthew Miles