A trip to the Barber

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

TWENTY-TWO YEARS AGO, WHEN I WAS hired at Cycle World, my wife Barbara and I sold our house in Wisconsin and moved to California. Determined to avoid the dreaded L.A. freeway commute, we rented a little house in Newport Beach, about six blocks from the CW office.

As we settled in, I soon realized that Newport and its next door neighbor, Costa Mesa, were filled with small pockets of industrial magic. Hidden in the back alleys and side streets amid the palm trees were virtual rabbit warrens of garages and shops that specialized in the most arcane and exquisite crafts.

There were builders of sailboats, restoration shops that concentrated on nothing but Jaguars, pre-war Alfas, old Moto Guzzis or vintage sprint cars. Ron Wood, famed builder of flat-track Nortons, had a shop just a few blocks away. The sheer concentration of technical skill and artisanship within walking distance of our house was enough to boggle the mind. Mine, anyway.

Of all these shops, however, my favorite was a place called British Marketing, owned by a genial expatriate Brit named Brian Slark. Brian’s specialty was Nortons. He had worked for Norton’s off-road competition department in England before moving to the U.S. in 1964. He also wrote a technical column for the Norton Owners Club Newsletter, which I avidly read. He was a skilled rider, a desert racer who had ridden for the Greeves 1SDT team at the Isle of Man in 1965.

Being on my second Norton Commando at that point, I naturally dropped by now and then for parts and advice, or just to talk about bikes. Brian and I were pretty much on the same philosophical wavelength regarding the good, the bad and the ugly of motorcycle design, and we soon became friends.

Eventually, Brian sold British Marketing and moved to St. Louis. There, he set up a business with Dave Mungenast, searching out, restoring and selling old British bikes that had been neglected or forgotten in the bams and garages of the Midwest.

During all these years, Brian and I have stayed in touch. We call each other about once a month to talk about bikes, though Brian sometimes calls just to taunt me about the weather in Wisconsin.

“Took a 200-mile ride Sunday on my KLR600. Lovely day, 70 degrees. Whatfl you do this weekend?”

“Ran the snowblower for two hours,” I

typically reply. “Then I fed some whale meat to the sled dogs.”

To make things worse, Brian and his wife Dian moved even farther south seven years ago, to Birmingham, Alabama.

“I’ve taken a job with George Barber as an in-house consultant at the Barber Vintage Motorsports Museum,” he told me. “You’ve got to come down and see this collection. It’s wonderful, and we Ye adding bikes all the time. Nice riding around here, too. Warm weather, great roads.”

Since then, Brian has invited me to come down several times, but I’ve never managed to break free and make the trip. Until last week.

My Ducati-riding buddy Pat Donnelly called on a cold winter afternoon and said he was selling his vintage Lotus 31 racecar to the Barber museum. “They’re adding a few cars to the motorcycle collection,” he said. “Would you like to help me tow it down there?”

On my way at last. Pat and I towed the Lotus down to Nashville, stayed overnight, and got to Birmingham at noon the next day. Slark met us at the museum, a rather nondescript industrial building in the heart of town, and introduced us to George Barber.

Barber, who made his fortune in the dairy business, immediately struck me as a modest and thoughtful man, with a real love-and knowledge-of cars and bikes. The Barber Museum may not look like the Guggenheim from the outside,

but to walk in through the front door is to enter another world; you feel like a treasure hunter opening an old chest to find it filled with the Crown Jewels.

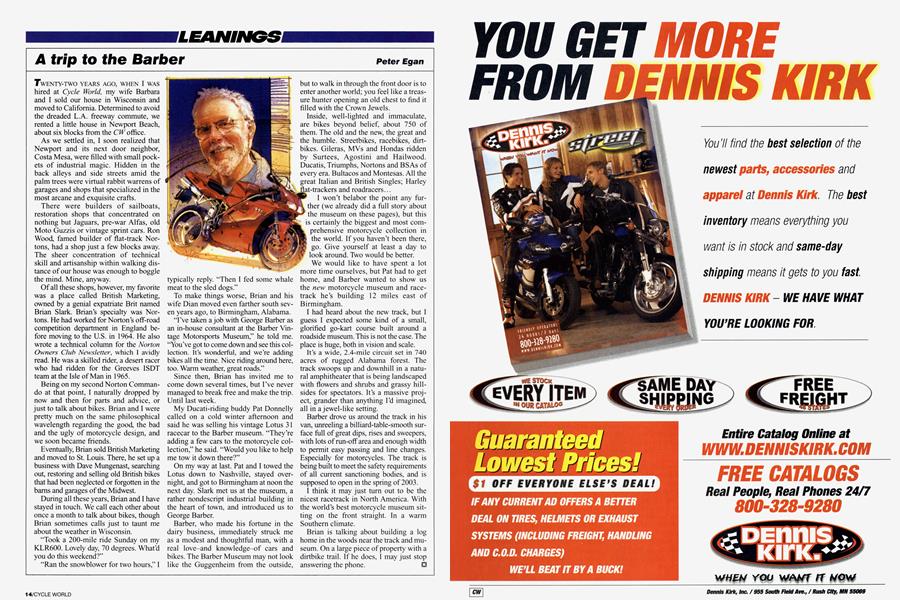

Inside, well-lighted and immaculate, are bikes beyond belief, about 750 of them. The old and the new, the great and the humble. Streetbikes, racebikes, dirtbikes. Güeras, MVs and Hondas ridden by Surtees, Agostini and Hailwood. Ducatis, Triumphs, Nortons and BSAs of every era. Bultacos and Montesas. All the great Italian and British Singles; Harley flat-trackers and roadracers...

I won’t belabor the point any further (we already did a full story about the museum on these pages), but this is certainly the biggest and most comprehensive motorcycle collection in the world. If you haven’t been there, go. Give yourself at least a day to look around. Two would be better.

We would like to have spent a lot more time ourselves, but Pat had to get home, and Barber wanted to show us the new motorcycle museum and racetrack he’s building 12 miles east of Birmingham.

I had heard about the new track, but I guess I expected some kind of a small, glorified go-kart course built around a roadside museum. This is not the case. The place is huge, both in vision and scale.

It’s a wide, 2.4-mile circuit set in 740 acres of rugged Alabama forest. The track swoops up and downhill in a natural amphitheater that is being landscaped with flowers and shrubs and grassy hillsides for spectators. It’s a massive project, grander than anything I’d imagined, all in a jewel-like setting.

Barber drove us around the track in his van, unreeling a billiard-table-smooth surface full of great dips, rises and sweepers, with lots of run-off area and enough width to permit easy passing and line changes. Especially for motorcycles. The track is being built to meet the safety requirements of all current sanctioning bodies, and is supposed to open in the spring of 2003.

I think it may just turn out to be the nicest racetrack in North America. With the world’s best motorcycle museum sitting on the front straight. In a warm Southern climate.

Brian is talking about building a log home in the woods near the track and museum. On a large piece of property with a dirtbike trail. If he does, I may just stop answering the phone.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMad Max Found!

May 2002 By David Edwards -

TDC

TDCRoom At the Top

May 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

May 2002 -

Roundup

RoundupBeyond the V-Rod: Harley's Next Revolution?

May 2002 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupDesmosedici!

May 2002 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

RoundupKawasaki's Secret Four-Stroke On-Track

May 2002 By Matthew Miles