SERVICE

Call in the Reserves

Paul Dean

I have a 1993 Kawasaki ZX-6 which, according to the owner's manual, the magazine tests and the dealership, is supposed to have a 4.8-gallon gas tank. But I've never been able to put more than 3.8 gallons in it. On a couple of occasions, I've ridden the bike until it began to sputter and almost die, then switched to Reserve and ridden another 20 miles to work, yet 3.8 gallons was still the most gas it has ever taken. The dealer says nothing is wrong with the tank, but I like to take long rides, and this problem keeps me nervously close to gas stations. The bike gets 40 mpg in town and 44-46 mpg on the highway. Is there any way to adjust the pickups in the tank to solve this problem or am I just shorted a gallon?

Paul Ragland Tucson, Arizona

According to our February, 1993, road test of the ZX-6-in which, as always, we measured the fuel capacity our selves-the tank holds 4. 7 gallons. Based on that test's best and worst mileage figures-53 and 42 mpg, respectively-the bike had a fuel range of between 197 and 246 miles. Our records don `t indicate how much fuel was remaining afler being switched to Reserve, though, so I can `t tell you how far our bike would go on the main tank. But it is quite common for some motor cycles-Japanese sport machines in particular-to have an unusually large Reserve capacity. I've ridden many that would still have well over a gallon left in the tank after I had ridden 10 or 15 miles on Reserve.

Here ’s what you need to do: Run your ZX-6 out of gas. With the tank already switched on Reserve, have a friend follow you in a car so he or she can carry a gas can filled with precisely 5 gallons of fuel, then simply ride until the engine stops running for lack of dead dinosaurs. Carefully refill the tank from the gas can and, using any kind of graduated cup or bottle, measure the fuel remaining in the can. Subtract that amount from five gallons and you ’ll then know exactly how much fuel your tank holds and approximately how far you can ride after switching to Reserve.

If you ’re still bothered by the short range of your main tank, you indeed can “adjust” it. First drain the tank, then remove the fuel petcock and simply shorten the tall, hollow tube that extends upward from its center. That tube is the pickup for the main tank, so its height determines how much fuel is available before the need to go on Reserve, which drains from the very bottom of the petcock. Don’t shorten the tube too much, though, or you won’t be able to travel very far on Reserve. Obviously, this modification will have no effect on the bike ’s overall range, but it will allow you to ride farther before switching to Reserve.

Does inertia curse va?

I bought a used `98 Ducati 916 from a guy who did a great job of upgrading the bike with a Ferracci exhaust, a new computer chip and a lightweight flywheel. The bike performs magnificently, but I have some concerns about the light flywheel. The engine idles terribly because of this change, and it also can be a bit annoying at low revs. I'm wondering what I am actually gaining with this lighter flywheel, and if it could impact long-term durability. I occasionally pick up the old, heavy flywheel and wonder if I should put it back on. I'd appreciate hearing the pros and cons on this issue, which might help me decide whether I should do something-or do nothing at all and just keep enjoying what happens when I twist the throttle!

Mike Vaughn West Bloomfield, Michiaan

The purpose of a flywheel is to provide the inertia necessary to smooth out potentially large variations in engine speed between combustion events. Unlike a jet engine, in which the combustion process is continuous, a twoor fourstroke engine only makes power for a brief period as each cylinder fires. The rest of the time, internal friction and the very act of propelling the vehicle are trying to slow the engine down. In the case of a two-cylinder four-stroke, the engine only fires once every revolution; and on a Ducati V-Twin, which has its cylinders angled at 90 degrees to one another, the interval between those firings is irregular, alternating between 270 and 450 degrees.

Thus, if the engine had no flywheel whatsoever, it wouldn’t idle at all, and it would be so unmanageable at lower rpm that it would shudder violently and stall without warning. Only at higher rpm would it smooth out; even then, snapping the throttle closed would slow the bike so abruptly that it’d be the equivalent of stomping on the rear brake pedal.

One way to better understand all this is to consider a simple rule regarding flywheel inertia: A flywheel absorbs energy as an engine accelerates, and gives that energy back as the engine decelerates. In other words, the more flywheel an engine has, the more acceleration that flywheel steals; but when the throttle is closed, that “borrowed” acceleration is returned in the form of a more gradual rate of deceleration.

The proper amount of flywheel for any engine depends upon that engine’s mission. If it’s intended to be an easygoing road motor, such as in a HarleyDavidson cruiser, great gobs of flywheel (which Harleys have) allow it to run very smoothly at low rpm and maintain a constant road speed without the need to closely monitor throttle position, but it doesn’t rev all that quickly, either. If the engine is intended for competition, as in a roadracer, for example, you’d want to maximize acceleration by having as little flywheel as possible. You’d need just enough to permit the engine to pull smoothly and strongly from the lowest rpm it would encounter on the track, which might be no lower than 4000 or 5000 rpm. And as far as a high-performance streetbike is concerned, it has to strike a happy medium, a compromise between those two extremes. It needs as little flywheel as is practical to enhance acceleration, but still enough to make everyday riding palatable.

With a dirtbike, however, reducing flywheel does not necessarily result in increased acceleration. Sometimes, offroad engines with very light flywheels tend to rev so quickly that they don’t allow the rear tire to hook up easily on slippery surfaces. Hence, these bikes often end up getting outrun by bikes that have less powerful engines but more flywheel, since that additional flywheel inertia helps them put more of their power on the ground.

On your 916, the light flywheel presents no reliability issues so long as you keep the motor spinning fast enough to run smoothly. But every time you let the revs drop down into the herky-jerky zone, you’re hastening the onset of driveline problems.

K-bike konsumption

I have a BMW K1200RS, 1998 edition. I bought it new in February of ’98 and have tallied 19,000 miles. I commute to work four days a week on the freeways and ride it on yearly trips up the Pacific Coast Highway, so the machine isn’t ridden that hard. My question is, what is an acceptable amount of oil for it to consume? I have been logging its recent consumption after I noticed that I always seemed to be “topping it off.” In a 300-mile interval,

I had to add V3 of a quart, and in the following 500-mile interval, I had to add V2 of a quart. Do I have a problem here or is this standard for the K engines?

K. Grant Posted on America Online

That rate of oil consumption, which is equivalent to a quart every thousand miles, is a bit on the high side, even for an engine with 19,000 miles on it; but in my opinion, it’s not bad enough to justify the expense of a rebuild. The Kmotors tend to use a little more oil-and

do so sooner-than their vertical fourcylinder counterparts. Without gravity to assist them in draining, the horizontal cylinders allow a bit more oil than normal to accumulate on cylinder walls and around valve guides; so, as rings and seals begin to exhibit any significant degree of wear, the oil in their vicinity is easily drawn into the combustion chambers and burned into vapor. Nonetheless, until your 1200’s rate of consumption increases to about twice its current level-say, a quart every 500 miles or so-I’d just keep riding and not worry about it.

Baby needs new shoes

Could you please recommend a set of replacement tires for my 1991 Honda ST 1100? The owner’s manual says to use a Metzeier 110/80V18-V240 on the front and a Metzeier 160/70VB17-V240 on the rear. Is there a more modern tire that I should or could use? I ride on high-speed freeways during the week and on backroads on the weekends.

Phil May Posted on America Online

Those bias-ply Metzelers are originalequipment replacements for the ST 1100, a motorcycle originally designed for the German market; but numerous other tires in those very same sizes, including many of the latest sport-touring radiais, will fit properly and work quite nicely. Actually, later-model ST 1100s equipped with ABS come from the factory fitted with radiais (a 160/70ZR17 on the rear and a 120/80ZR18 up front). No one at this magazine has personal experience with an ST that underwent the change from bias-ply to radial rubber, so I can’t recommend a specific tire or talk about any handling improvements, but you ’re not likely to go wrong with any of the major brands.

A lean machine

I am having problems with my 1996 Honda CBR900RR. I purchased the bike in February of 1999 with 6400 miles on it. I had a complete service (oil, filter, valve adjustment, carb synch, brakefluid replacement) done at roughly 8800 miles. The bike ran great for over a year, with only the occasional exhaust pop during deceleration. I now have 14,000 miles on the clock, and a few months ago, it began to have trouble with coldstarting. When I would pull the choke and hit the starter (no throttle), it would fire right up. But after a few seconds, the idle would settle down and the engine eventually sputter off and stall if I didn’t blip the throttle a couple of times. My mechanic suggested a change of plugs, so I installed a new set of NGK CR9EA-9 plugs, but the old problem persists, along with a new one: When I have the throttle partially cracked open between 3000 and 4000 rpm, I get a noticeable surging and exhaust popping, most noticeably at around 3500 rpm. I am worried about doing damage to the engine by running it like this. I’ve been told that my plugs may be the culprit because they’re supposed to have resistors in them, but I don’t know whether they do or don’t. Incidentally, the bike has been slightly modified with a jet kit, an ignition advancer and a full exhaust

system from Two Brothers. Any and all help you can offer me will be greatly appreciated. John Passarella

Posted on America Online

The sparkplugs are not the culprit. The engine seems to be running excessively lean, which would cause it to exhibit all the symptoms you describe.

There are only two causes of excessive leanness: too little fuel or too much air. If the problem were due to fuel starvation, such as a restricted fuel line or fuel-tank vent, the engine would misbehave more noticeably at higher rpm than at or near idle. And the odds of all four carb-foat levels dropping out of adjustment at the same time or all the jet orifices clogging simultaneously are astronomically low. Which means that too much air is the probable cause. And that, in turn, leads us to the rubber tubes that connect the carbs to the intake manifold, virtually the only place where air that hasn 7 been mixed with fuel can enter the intake stream.

To determine the source of the leak, start the engine, let it warm up slightly and, one way or another, get it to idle, even if you have to turn the idle-speed adjustment screw in much farther than normal. Then spray WD-40 around the area between the carburetors and the cylinder head, concentrating mostly on the joints between the rubber tubes and the intake manifold, as well as between the tubes and the carburetors themselves. As soon as even a small amount of WD40 gets sucked into the intake stream through an air leak, whitish smoke will start issuing from the exhaust. If you still need to pinpoint the exact location of the leak, stop spraying and let the smoke die down, then attach the little plastic straw that plugs into the nozzle of the WD-40; it allows you to direct the spray over a more concentrated area. Carefully spray around each joint, one by one, until the smoke reappears. When that happens, you will have found the leak. □

Got a mechanical or technical problem with your favorite ride? Can’t seem to find workable solutions in your area? Maybe we can help. If you think we can, either: 1) Mail your inquiry, along with your full name, address and phone number, to Cycle World Service, 1499 Monrovia Ave., Newport Beach, CA 92663: 2) fax it to Paul Dean at 949/631-0651; or 3) e-mail it to CW1Dean@aol.com. Don’t write a 10-page essay, but do include enough information about the problem to permit a reasonable diagnosis. And please understand that due to the volume of inquiries we receive, we can’t guarantee a reply to every question.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontTales From the Tour

February 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Town Too Far

February 2001 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCGordon Jennings

February 2001 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

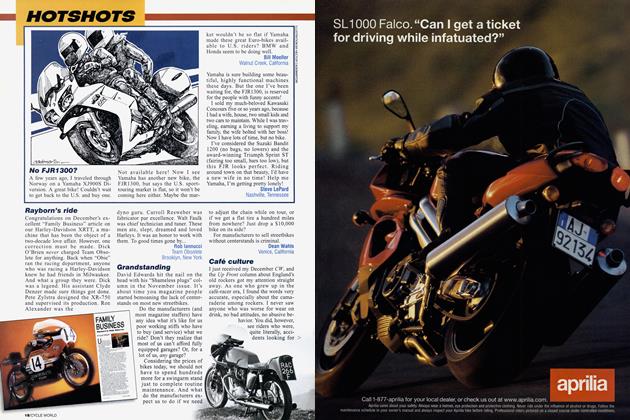

DepartmentsHotshots

February 2001 -

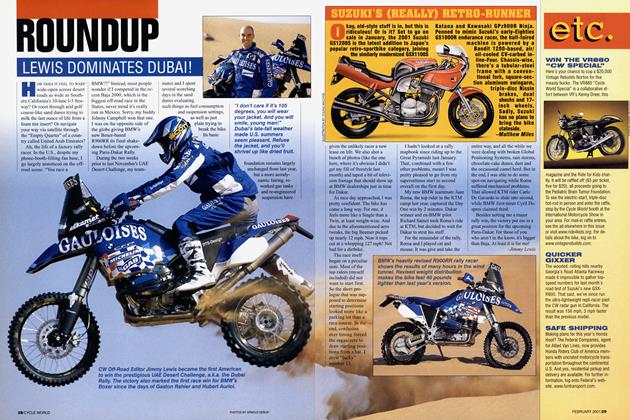

Roundup

RoundupLewis Dominates Dubai!

February 2001 By Jimmy Lewis -

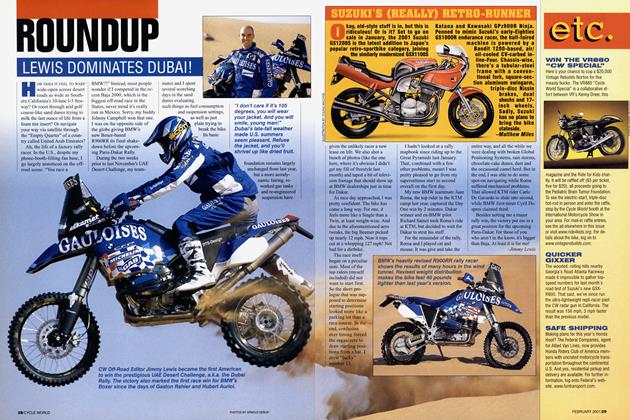

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki's (really) Retro-Runner

February 2001 By Matthew Miles