Japan's gift to the worlth revisited

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

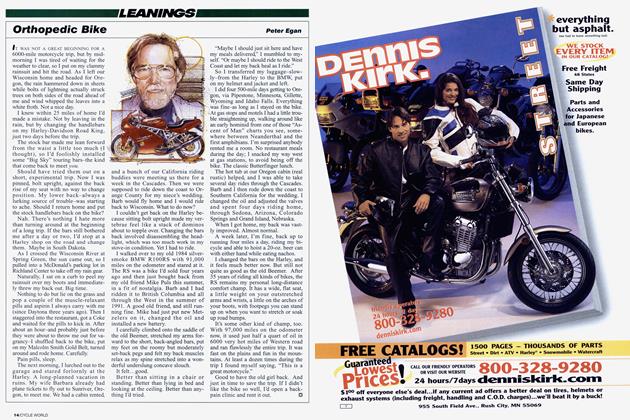

IT WAS ONE OF THOSE SUMMER MORNings from childhood memory, where you step outside and find rays of sunlight slanting down through the green trees and filtering through pockets of ground fog like laser beams from heaven. If you painted a scene like this, critics would dismiss your work as sentimental and mawkish. If you wrote about it, they’d do the same thing, so I won’t say another word. Suffice it to say, it was a beautiful Saturday morning.

And I was up early, planning to drive my van down to Blackhawk Farms racetrack to crew for my buddy Pat Donnelly, who was racing his vintage Lotus 31 Formula Ford that day.

I threw my hat and sunglasses in the c van and was about to dump ice into our green Coleman cooler when I looked out the screen door and said, “Hey, wait a minute: If I don’t take this big cooler along, I could ride a motorcycle! I’ll buy lunch and drinks at the concession stand with money I save on gas!”

Flawless economics, right out of Harvard Business School, or maybe an old Steve Martin movie.

So I tossed my few belongings into a backpack, grabbed a helmet and climbed on my green 1973 Honda CB350. Or I should say my wife Barbara’s CB350; she seems to be staking a territorial claim by riding it almost daily. It’s the only bike we own whose mass, mechanical flukes and/or sidestand deployment are unintimidating to her.

Yes, after months of fiddling, I finally have the Honda vertical-Twin running. No small task. It took a full tune-up and two “professional” carb rebuilds, one by me (hence the quotation marks) and one by a reputable shop, to make it run exactly as poorly as it did the day I bought it last winter, which is to say surging and bucking, with a bad case of the blind staggers.

I finally pulled an old pair of carbs off my battered parts bike and-without even looking inside the float bowls-bolted them on the “good” bike. It started right up.

So much for Science and Knowledge.

Anyway, with my Mystery Cure Keihins bolted on, I motored smoothly south on tree-lined country roads. The bike was running great.

After all these years, the CB350 is still a surprisingly competent road bike. It’s roomy and comfortable with relatively plush suspension, styled and sized to make you believe you are on a motorcycle that was designed for adults. The exhaust note, too, sounds bigger and harder-hitting than the displacement would seem to warrant. There’s a reasonable amount of midrange torque and a nice little surge of camminess at the upper end.

The CB350 will cruise at 70 mph and above, but it’s smoothest somewhere in the 60-65 mph range, with the tach hovering around 6000 rpm, well below its 9200-rpm redline. At cruise speed, the engine “hunts” a little, as if the CV carb diaphragms are half a step behind the throttle position. The CB350 I had new in 1973 did this, too.

Which is one of the reasons I eventually convinced myself I needed to trade it in on a Norton Commando. The Norton carbs worked better, but the exhaust system fell off. It’s always something.

I’m not sure I’d want to ride a CB350 across the United States anymore, spoiled as I am by the low-key bang of larger pistons, but an 80-mile roundtrip to the track and back was just about right for a relaxing test ride on the open road.

And if the bike was at least adequate on the highway, I soon discovered that it was perfect as a pitbike.

During the day, when Pat went out on the track for practice or qualifying, I was able to jump on the 350, hit the starter button and visit three or four different corners during each session.

Parking? No problem. Swing the sidestand forward as you roll to a stop and step off. You’re there. Time for lunch? Ride right up to the concession stand, park 10 feet away and walk to the window. Effortless.

The paddock was full of small scooters, mostly Honda Sprees, but I really couldn’t observe any advantage they had over my 350, except perhaps their storability on trailers. The main difference seemed to be that, at the end of the day, I could put my helmet on and ride home on the highway.

At one point during the afternoon, I sat in the shade of Pat’s canopy, drinking jSome Gatorade and looking at the 350, trying to think what other bikes would serve these dual functions. If I’d brought . one of my big road-burners to the track, I probably would have left it parked for the day. Repeated starts and stops and short rides seem abusive to a big-bore streetbike. Also, the bikes are clumsier to park and maneuver. My old Triumph 500 might work, but then there’s turning on the fuel, tickling the carb, kicking the lever, etc. And it’s old and British and deserves a proper warm-up. And you’ve still got to get home, maybe after dark...

Seems that after all this time the thing that originally sold so many small and mid-sized Japanese bikes in general-and a zillion Honda CB350s in particularstill works. It’s that inviting quality of low effort in starting, stopping and parking. The painless threshold.

Before these motorcycles came along, starting up a European or American bike was an Event, almost like getting ready for an airplane flight or a parachute jump. But the Japanese made operating a motorcycle as clean and easy as using your Chevy Biscayne. Easier, if it wasn’t raining. They raised performance and lowered entry requirements at the same time.

And this is probably what made me take the CB to Blackhawk instead of my van-or another bike. The 350 simply invited me to jump on and go, without ritual or preparation. It’s a spur-of-the-moment bike, the motorcycle equivalent of fast food, for those times when a fivecourse dinner is just too much.

You don’t need a 30-year-old bike to enjoy this quality, of course. Any number of electric-start dual-sport 250s and 350s have it now. So does the Harley 883 Sportster, strangely enough.

Actually, all bikes are better in this regard than they used to be, but the CB350 is a living reminder that it was largely the Japanese who raised our standards. They invented the civilized pitbike that doubles as a real motorcycle. Or vice versa.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue