At the edge of magic

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

FOR MY 53RD BIRTHDAY A FEW WEEKS ago, I bought myself a drum kit, a set of used black Ludwig Rockers owned by a recent college graduate who was moving to California (and presumably a smaller apartment), and signed up for my first drum lesson.

After years of playing guitar in various garage bands, I thought it might be fun to learn something new. I have the rhythmic sense of a dirtbike doing high-speed endoes across the desert, but I figured it couldn’t hurt to learn how to walk and chew gum at the same time, after all these years.

So there I was last night, just home from my second big drum lesson, attempting to play a double-bass pattern while hitting quarter-notes on the ride cymbal and the 2 and 4 beats on the snare and high-hat. Let me just say that, while the drool was flowing freely, I did not actually bite my tongue off, and actually got into a sustainable groove after about an hour of grim concentration. Pretty soon I was in the usual mesmeric trance that comes with minor sonic accomplishments in people like me, and the hours were flying by.

Only one thing can interrupt an ecstatic state like this, of course, and that’s repositioning your Triumph for a better angle of viewing.

Yep. The first thing I did after buying the drums and installing them in the carpeted “band comer” of my workshop, was to move a couple of my bikes around so I could view their most flattering angles from my drummer’s throne. One of the beauties of drumming, you see, is that it’s not always necessary to look at the dmms while you play (I have to stare laser holes in my guitar neck when I’m learning something new), so you can absorb visual and aural information at the same time.

And with the right bike parked about 15 feet in front of your dmms, the combination produces an electrical glow somewhere in the temporal lobe that could power a 10-amp battery charger, or a small subdivision in northern California.

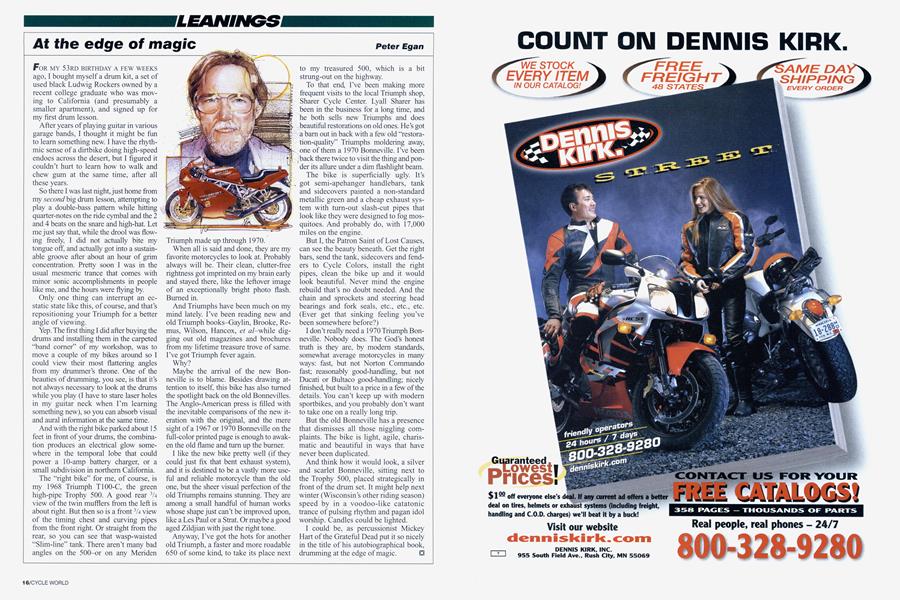

The “right bike” for me, of course, is my 1968 Triumph T100-C, the green high-pipe Trophy 500. A good rear 3A view of the twin mufflers from the left is about right. But then so is a front 3A view of the timing chest and curving pipes from the front right. Or straight from the rear, so you can see that wasp-waisted “Slim-line” tank. There aren’t many bad angles on the 500-or on any Meriden Triumph made up through 1970.

When all is said and done, they are my favorite motorcycles to look at. Probably always will be. Their clean, clutter-free rightness got imprinted on my brain early and stayed there, like the leftover image of an exceptionally bright photo flash. Burned in.

And Triumphs have been much on my mind lately. I’ve been reading new and old Triumph books-Gaylin, Brooke, Remus, Wilson, Hancox, et a/-while digging out old magazines and brochures from my lifetime treasure trove of same. I’ve got Triumph fever again.

Why?

Maybe the arrival of the new Bonneville is to blame. Besides drawing attention to itself, this bike has also turned the spotlight back on the old Bonnevilles. The Anglo-American press is filled with the inevitable comparisons of the new iteration with the original, and the mere sight of a 1967 or 1970 Bonneville on the full-color printed page is enough to awaken the old flame and turn up the burner.

I like the new bike pretty well (if they could just fix that bent exhaust system), and it is destined to be a vastly more useful and reliable motorcycle than the old one, but the sheer visual perfection of the old Triumphs remains stunning. They are among a small handful of human works whose shape just can’t be improved upon, like a Les Paul or a Strat. Or maybe a good aged Zildjian with just the right tone.

Anyway, I’ve got the hots for another old Triumph, a faster and more roadable 650 of some kind, to take its place next to my treasured 500, which is a bit strung-out on the highway.

To that end, I’ve been making more frequent visits to the local Triumph shop, Sharer Cycle Center. Lyall Sharer has been in the business for a long time, and he both sells new Triumphs and does beautiful restorations on old ones. He’s got a bam out in back with a few old “restoration-quality” Triumphs moldering away, one of them a 1970 Bonneville. I’ve been . back there twice to visit the thing and ponder its allure under a dim flashlight beam.

The bike is superficially ugly. It’s got semi-apehanger handlebars, tank and sidecovers painted a non-standard metallic green and a cheap exhaust system with turn-out slash-cut pipes that look like they were designed to fog mosquitoes. And probably do, with 17,000 miles on the engine.

But I, the Patron Saint of Lost Causes, can see the beauty beneath. Get the right bars, send the tank, sidecovers and fenders to Cycle Colors, install the right pipes, clean the bike up and it would look beautiful. Never mind the engine rebuild that’s no doubt needed. And the chain and sprockets and steering head bearings and fork seals, etc., etc., etc. (Ever get that sinking feeling you’ve been somewhere before?)

I don’t really need a 1970 Triumph Bonneville. Nobody does. The God’s honest truth is they are, by modem standards, somewhat average motorcycles in many ways: fast, but not Norton Commando fast; reasonably good-handling, but not Ducati or Bultaco good-handling; nicely finished, but built to a price in a few of the details. You can’t keep up with modern sportbikes, and you probably don’t want to take one on a really long trip.

But the old Bonneville has a presence that dismisses all those niggling complaints. The bike is light, agile, charismatic and beautiful in ways that have never been duplicated.

And think how it would look, a silver and scarlet Bonneville, sitting next to the Trophy 500, placed strategically in front of the drum set. It might help next winter (Wisconsin’s other riding season) speed by in a voodoo-like catatonic trance of pulsing rhythm and pagan idol worship. Candles could be lighted.

I could be, as percussionist Mickey Hart of the Grateful Dead put it so nicely in the title of his autobiographical book, drumming at the edge of magic. □