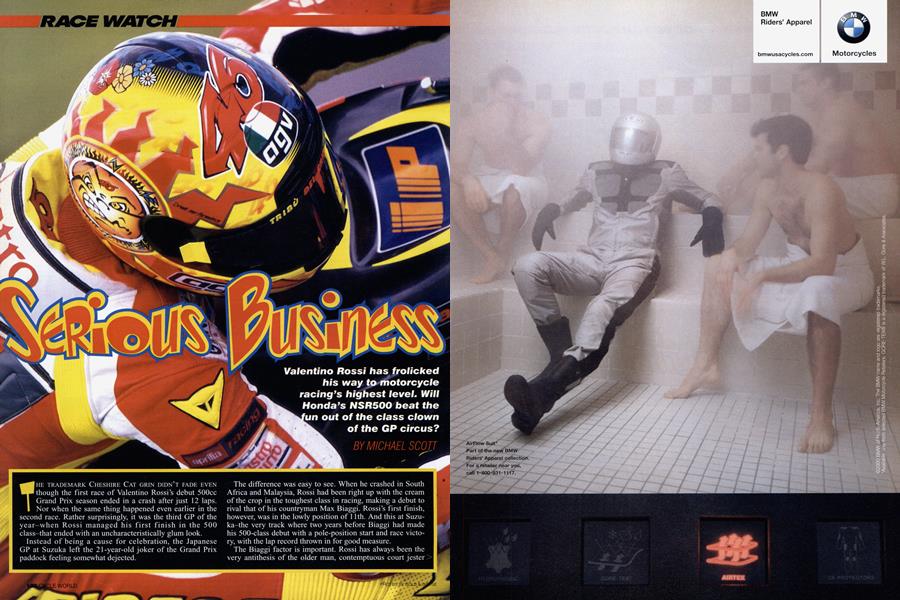

SERIOUS BUSINESS

RACE WATCH

Valentino Rossi has frolicked his way to motorcycle racing’s highest level. Will Honda’s NSR500 beat the fun out of the class clown of the GP circus?

MICHAEL SCOTT

THE TRADEMARK CHESHIRE CAT GRIN DIDN'T FADE EVEN though the first race of Valentino Rossi's debut 500cc Grand Prix season ended in a crash after just 12 laps. Nor when the same thing hannened even earlier in the second race. Rather surprisingly, it was the third GP of the year-when Rossi managed his first finish in the 500 class-that ended with an uncharacteristically glum look.

Instead of being a cause for celebration, the Japanese GP at Suzuka left the 21-year-old joker of the Grand Prix paddock feeling somewhat dejected.

The difference was easy to see. When he crashed in South Africa and Malaysia, Rossi had been right up with the cream of the crop in the toughest class in racing, making a debut to rival that of his countryman Max Biaggi. Rossi’s first finish, however, was in the lowly position of 11th. And this at Suzuka-the very track where two years before Biaggi had made his 500-class debut with a pole-position start and race victory, with the lap record thrown in for good measure.

The Biaggi factor is important. Rossi has always been the very antithesis of the older man, contemptuous court jester to Biaggi’s self-important, self-styled emperor. And in the dynamics of their relationship-a relationship conducted once removed, since they rarely speak-this was a rare setback for the cheeky upstart from the Adriatic Coast. Rossi is more accustomed to being one-up in his perpetual quest to prick the vanity of his Roman rival.

All of which, of course, has a greater meaning. Valentino is in the 500 class now, up with the big boys. It might have been predicted that he wouldn’t have it all his own way. At the same time, Biaggi, after his splendid start, has hit rough timesswitching from Honda to Yamaha only to find life even harder on a factory team than his former semi-works satellite squad, and furthermore making a slow start to 2000, unexpectedly overshadowed by his own teammate, Spaniard Carlos Checa.

Which in turn begs the question: Can the teenage darling of the 125 class survive the transition, while still preserving the fresh, fun-loving personality that made him not just the man to challenge the godlike persona of Biaggi, but one of the most popular riders in the whole sport?

Some history is required. Valentino is the son of Seventies GP racer Graziano Rossi. Pictures show the babe in arms on the rostrum with his

father long before he could talk. (Said father, not surprisingly, was rather a fun-lover himself, sporting flowing long hair and a reputation for crazy antics at a time when racing was a lot wilder and less disciplined than today.)

His parents split up, and Valentino divided his time between the two households, with dad-much pestered, he now claims-able to help with his racing ambitions in the thriving minimoto series on the many go-kart tracks in the resort towns that cluster around Rimini and the Adriatic seaside. Graziano fervently denies that he ever pushed his son. It happened naturally, to a kid who rode a minibike before he’d ever tried a bicycle.

Talent will come out, of course, and in his early teens, Valentino was spotted by Aprilia. “He reminded me of

Kevin Schwantz,” explains then racing boss Carlo Pernat, who had also scouted Biaggi a couple of years before. Rossi’s subsequent international racing history began forthwith, moving from Italy’s thriving and highly productive Production Sport 125 series when he was 14 to GP-class 125 racers two years later. He won the national championship and was third in the 125 European Championship. In February of 1996 he turned 17, old enough for GPs, and won a debut-season race to became the youngest-ever GP winner (a feat since superseded by

countryman Marco Melandri after the age limit was lowered to 16). And in 1997 he won the 125 title, in crushingly dominant style, displacing the Japanese kings of the class with a cheery laugh, and the affectionately satirical name “Rossifumi” (a play on Norifumi Abe’s first name) across the back of his leathers. Rossi moved straight into 250s, and adapted almost instantly to the bigger bikes, winning five races in his first season to finish runner-up, then sweeping to the title in 1999, again completely dominant.

All the way through, and especially in the earlier years, Graziano was there (as he later explained) to protect his son from the effects of too much fame and fortune too young, and also to help him learn not just how to ride fast, but how to control the pace of a race. Father and son made quite a pair. At that time Valentino wore his hair long, page-boy style. With his hairless chin and gangling limbs, he was quite the androgenous racer. The close crop came only after he’d won his first title. Dad would be visible only now and then in the background, nowadays sporting a pony-tail almost waist-length.

Quite how much of a moderating influence Graziano exerted may be open to some question, since Valentino arrived at a GP race in 1998 with his head ostentatiously bandaged after he and fellow racer Loris Capirossi had survived a heavy crash in a Porsche driven by Rossi’s father. Valentino wore the bandage even on the rostrum after the race.

Which was an early example of another hugely significant aspect of his character-a talent for showmanship that he has always been able to carry off with flair and originality. Indeed, the Rossi post-race shows soon became as characteristic as his grin.

They began with simple exuberance in his 125 days, but already the kid had a following of fans with a sufficient level of organization to orchestrate increasingly elaborate displays after each win, escalating from flagwaving to full-scale fancy-dress pantomimes. Week by week, racing would wait to see what sort of a costume Rossi would don for his next visit to the rostrum-an open-face helmet, shades and a beach towel in Italy, Gothic mace in Germany, Robin Hood garb at Donington Park in England, close to Sherwood Forest...

“It is my fans-they made it for me,” Rossi would say. But he was a morethan-willing participant, and in fact the best shows were spontaneous rather than orchestrated, ranging from climbing the fences like a monkey to.. .well, read on.

The most famous came last year, at Jerez, Spain. Rossi won the 250 race in majestic style-his first victory after a slow start to his first (and last) championship year in the class. He was so far ahead that he stood solemnly to attention on the footpegs past the flag. Then came the slow-down lap.

Now, Jerez is unusual in having prefab lavatories at strategic points on the infield-for the marshals, obviously. Rossi was ready. He jammed on the brakes, parked the bike hurriedly, and rushed toward one of the huts, unzipping his leathers ostentatiously before slipping inside, emerging a minute later looking much relieved. So that’s why he’d been in such a hurry to get the race over with...

These time-consuming theatrics were enjoyable, but in direct conflict with strict rules designed to get riders to the rostrum in time to fit in with international television schedules. So the FIM started to discipline him-first a warning, then a fine. Rossi could afford to laugh. “Aprilia pays the fine for me, because it only happens after I have won the race, and they are very happy.” But he found the whole thing displeasing. “They want to make bike racing like Formula One, with no personalities. I don’t like that. I will carry on.”

This was a little unfair, since he’d gotten away with another flagrant breech in another Spanish race, at Catalunya, where he’d stopped to pick up a friend dressed as a rooster-a favor to one of his long-standing personal sponsors who runs a chicken restaurant. The rules are quite clear: no passengers. But 1RTA boss Paul Butler deflected possible punishment by matching humor with humor. “The rules say you may not pick up another person. But they don’t say anything about chickens.”

In fact, this was not Rossi’s first passenger. Back in 1997, his 125 title year, he’d run his victory lap at Mugello with an inflatable doll as companion, which was wearing a shirt (just so there could be no mistake) with the name “Claudia Schiffer” on the back. This was no idle piece of japery, but a barb aimed directly at Biaggi, who had during the previous winter made some capital out of a rumor linking him with supermodel Naomi Campbell. It was not the first time Rossi had made fun of Max, nor by any means the last.

“I don’t like him as a person, or as a rider,” he explained at the time. “I didn’t care, until he came up to me at dinner one night, and said, ‘Don’t make too much noise,’ like he is the most important Italian rider, and I must be junior to him.” Rossi is too good-humored for this to be taken as serious malice-just another thing that he finds amusing. But it could escalate, of course, especially since the reason he moved to 500s this year, instead of accepting Aprilia’s bigmoney offer of another year on the 250, was to get to grips with Mad Max on the track for the first time.

For now, the situation is merely simmering, and again Rossi can attribute most excesses to his fans. Like the website in his name, which carries a mocking picture of Biaggi ignoring the black flag at Barcelona-a notorious incident in 1998. And another website rumored to run a competition for the most insulting piece of doggerel verse about Biaggi.

Things will get more serious, of course. The pair are racing each other, Rossi on a Honda, Biaggi on a Yamaha and with the considerable advantage of two years of experience on a V-Four 500.

Like his older rival, Rossi started extremely well. The first time he tested the 500 Honda, he ran laprecord speeds at Jerez. “I’m sur-

prised that it is not more difficult,” he said. The very remark reveals his lack of experience-a matter put into perspective not by his crashes in the first two races, both a simple matter of over-exuberance and excessive lean angles, but by his troubles in the third, qualifying 13th and finishing 1 1 th at the difficult and challenging Suzuka circuit.

It was the retired Mick Doohan who summed it up from his place in Rossi’s pit. (The former five-time World Champion is not involved with the team, as had been planned originally, and instead works for HRC as a whole. But he spends most of his time in the Italian’s pit, since Rossi inherited his old crew, and he feels at home.) “He’s having trouble because he’s not getting much feeling from the bike. That’s where the experience helps. You know when it’s going to break away. You can predict the unpredictable. Until you get that feeling, you have to be either very brave or very stupid to push a 500 to the limit.”

Rossi can on occasion be both of those things, but he is rapidly learning that tricks he could get away with on a 125 and a 250 are punished when you try them on a 500. In both previous races, he admitted the crashes took him by surprise. So, too, did the difficulties of getting up to speed at Suzuka.

For the present, this has left young Valentino somewhat sobered. The hairstyle is as crazy as ever, but the grin is in suspension.

Those who know him also know it is only a matter of time. He’ll gain the confidence he needs, and he’ll become a candidate for the championship. He certainly has time on his side. His swaggering riding style will re-emerge, and the resemblance to Kevin Schwantz become all the more obvious to all the more people. As Garry Taylor, Schwantz’s former team boss at Suzuki, said when contemplating Rossi as a future rival to current incumbent Kenny Roberts: “It’s been easy to beat Rossi so far this year, but it’ll get a lot harder.”

Rossi’s crew chief Jerry Burgess certainly agrees, and he’s finding the experience entertaining after almost 10 years of hard work (and big rewards) doing the same job with Doohan. “We’re expecting everything from Valentino, and it’s a lot of fun working with him,” he said. “Mick and Alex (Criville) never wanted to try anything new. Mick always wanted last year’s suspension, and he wouldn’t even look at a power shifter. Valentino has one because he’s used to using one, and he’s open to other electronics as well. It gives us a chance to develop new things that have had to be kept on the back-burner for the last couple of years. As well as educating him as a 500 rider, we will also be learning from him, because he has such a fresh viewpoint.”

While this may be so, riding what is considered the best bike in the paddock, and one tuned by Doohan’s old crew, means Rossi’s got big boots to fill. Hopefully, his floppy clown shoes will fit and he can find success, with a lot of fun for all of us along the way.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

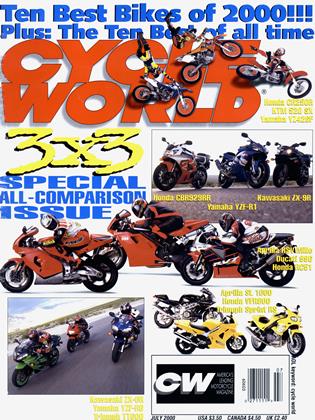

Up Front

Up FrontThe Ten Rest, 2000

July 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Perfect Baja Bike

July 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCCounting Cracks

July 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

July 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupFriedel Münch Strikes Again

July 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupAprilia Buys Moto Guzzi

July 2000 By Bruno De Prato