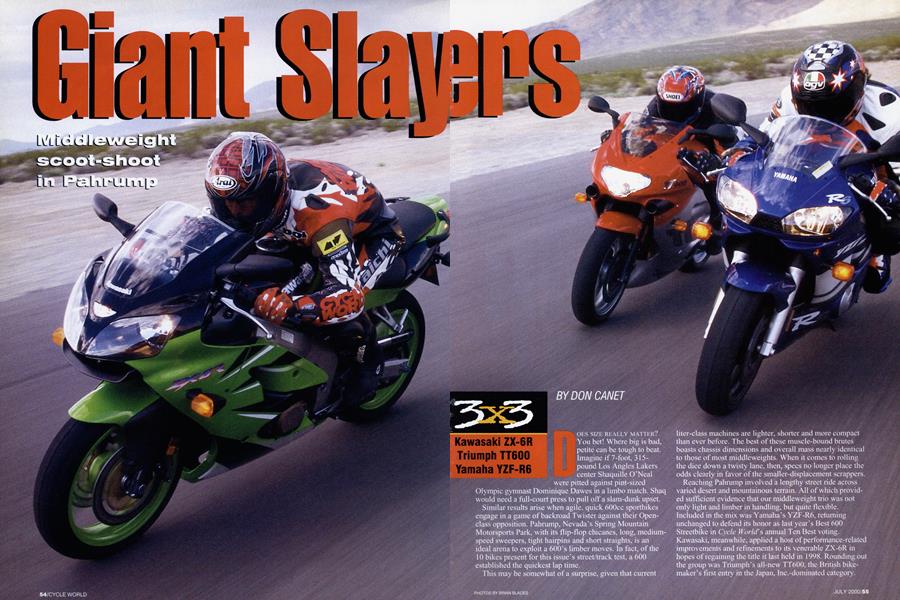

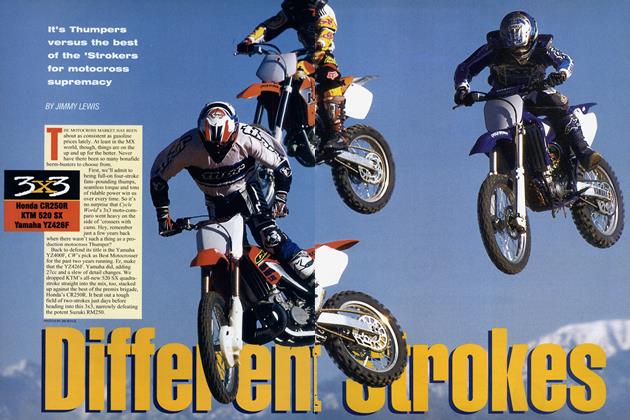

Giant Slayers

Middlewight scoot-shoot in Pahrump

DON CANET

DOES SIZE REALLY MATTER? You bet! Where big is bad, petite can be tough to beat. Imagine if 7-foot, 315pound Los Angles Lakers center Shaquille O'Neal were pitted against pint-sized Olympic gymnast Dominique Dawes in a limbo match. Shaq would need a full-court press to pull otia slam-dunk upset.

Similar results arise when agile, quick 600cc sportbikes engage in a game of backroad Twister against their Openclass opposition. Pahrump, Nevada’s Spring Mountain Motorsports Park, with its flip-flop chicanes, long, mediumspeed sweepers, tight hairpins and short straights, is an ideal arena to exploit a 600’s limber moves. In fact, of the 10 bikes present for this issue’s street/track test, a 600 established the quickest lap time.

This may be somewhat of a suiprise, given that current liter-class machines are lighter, shorter and more compact than ever before. The best of these muscle-bound brutes boasts chassis dimensions and overall mass nearly identical to those of most middleweights. When it comes to rolling the dice down a twisty lane, then, specs no longer place the odds clearly in favor of the smaller-displacement scrappers.

Reaching Pahrump involved a lengthy street ride across varied desert and mountainous terrain. All of which provided sufficient evidence that our middleweight trio was not only light and limber in handling, but quite flexible.

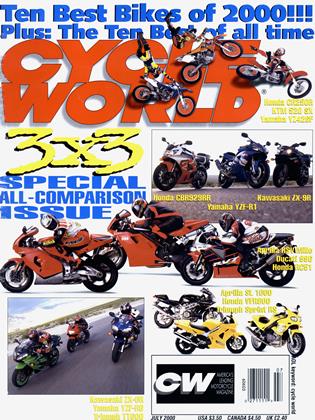

Included in the mix was Yamaha’s YZF-R6, returning unchanged to defend its honor as last year's Best 600 Streetbike in Cycle World's annual Ten Best voting. Kawasaki, meanwhile, applied a host of performance-related improvements and refinements to its venerable ZX-6R in hopes of regaining the title it last held in 1998. Rounding out the group was Triumph's all-new TT600, the British bikemaker’s first entry in the Japan, Inc.-dominated category.

KAWASAZKI ZX-6R

Ups A Class locomotive A Roomy ergonomics A Superior stablity

Downs ▼ Too-firm compression damping ▼ Seat slightly sharp-edged ▼ Most expensive of the Japanese 600s

Perhaps you’re wondering why Honda’s highly touted CBR600F4 or Suzuki’s GSX-R600 weren’t included. It’s not that these bikes don’t belong in this group, but they both lost out to the R6 last year, and bold new graphics alone weren’t enough to turn the tables this time around. Besides, this issue’s 3x3 theme left no room for a fourth and fifth set of wheels.

Of the 600s featured here, many similarities exist. Each is powered by a liquidcooled inline-Four that displaces 599cc. Dual overhead cams and four valves per cylinder are also standard fare, as are sixspeed gearboxes and wet multi-plate clutches feeding power through chain final-drives. Each machine also features ram-air induction for a cool, densely packed air/fuel mix, with ignition by lightweight, high-energy stick-type coils.

While the Kawasaki and Yamaha remain traditional in their use of Keihin CV carburetors, Triumph has injected some new technology previously absent in the 600 class. Like most of its Brit siblings, the TT600 uses a Sagem electronic engine-management system to control fuel delivery and spark timing.

In theory, then, the TT’s fuel injection would provide smooth running under a wide range of conditions. Turns out, Triumph was still in the process of refining the TT’s fuel mapping when our testbike arrived. Cold-blooded starts and a lengthy warm-up period were the first indications that all was not well within the TT’s brain. Worse still, a pronounced 4000-rpm stumble hampered the bike’s in-town aptitude. If the engine was not revved clear of the stutter spot before an upshift was attempted, revs would fall into the power pit, which promoted herky-jerky shifts.

YAMAHA YZF-R6

UPS A Racebike feel A Nimble handling A Potent top-end rush

Downs Requires extra effort to ride fast Less forgiving at limit

Suspect clutch action further hindered the TT’s quest for praise. Not only was the lever a reach for even larger hands, but the clutch itself was intermittently grabby and prone to chatter-something I hadn’t experienced on the two TT600s I rode at Triumph’s French press launch.

No one complained about the Triumph’s raised clip-onstyle handlebars, though, particularly during long freeway stints. The TT also offers decent wind protection, matching that of the R6 but falling short of the taller windscreen of the ZX. Of the three bikes, the YZF’s riding posture is the most aggressive, placing more weight on the rider’s wrists and forearms. Larger testers lauded the ZX as being comparatively roomy, while noting that the TT’s seat-to-peg relationship was a tad tight.

TRIUMPH TT600

Ups A Telepathic steering A Ultra-linear power delivery A Alternative to status quo

Downs ▼ Lacks refinement ▼ Jelly-bean styling ▼ Expensive

The TT’s engine vibrates slightly more, too. The bike is not unpleasant to the touch, but the rear-view mirrors blur at virtually any rpm. The ZX-6R has the silkiest mill of the lot. It also drew praise

for its torque-rich powerband.

As the king of top-gear roll-ons, the ZX places the least importance on gear selection. This midrange advantage pays big dividends in real-world use.

Kawasaki’s slick-shifting gearbox earned top honors, too, while the Yamaha’s positive-shifting tranny registered a close second. Once again, the TT shows promise with buttery-smooth cog selection, but every so often it delivered notchy feel or even an occasional false neutral-probably not helped by the aforementioned clutch conundrum.

Top scores for suspension compliance were

awarded to the YZF, while the remaining two machines felt a bit harsh in the rear when encountering sharp bumps. Otherwise, on the street, we never found fault with the bikes’ brakes, cornering clearance or handling. Would the racetrack prove any different?

Standard street suspension settings were retained during my first rotation on the track. As expected, all three machines worked well, but displayed a hint of excessive chassis pitch when I began to push the pace. Spring preload and damping settings were firmed up in preparation for a second series of timed hot laps.

First up, again, was the Triumph. While its acceleration off comers felt softer than that of its peers, keeping the rev counter between 10,000 and 14,000 rpm helped to maintain a good head of steam. I was immediately reminded of the late Eighties, when I raced a Suzuki 600 Katana in Supersport events. Back in the day, the “Can-a-tuna” was an underdog, but it held its own by virtue of its forgiving nature. So, too, the TT600. The bike’s rounded shape resembles that of an updated Katana, and the TT is equally friendly when ridden to its limits. Those limits, by the way, are in tune with current times.

Cornering clearance is excellent, with only the footpeg feelers scratching the pavement with any regularity (the leftside engine cover and sidestand nicked the deck once). The stock Bridgestone BT-010 radiais offer impressive grip, and allowed cornering speeds that bordered on the absurd. Frontend feel and feedback is second to none, as is the TT’s light, neutral steering. These factors add up to a bike that is both easy to ride and extremely forgiving, even at the limit. Eyebrows were raised when the Unipro timing system displayed the quickest time yet, a 1:47.50, which was several seconds quicker than the times recorded by other testers aboard liter-class machines.

Alas, the TT’s triumph was short-lived. Down to business aboard the firmed-up R6,1 was able to take full advantage of the Yamaha’s quicker-revving engine and 23-pound weight advantage. This, despite the fact that the front end lacked the confidence-inspiring stick provided by the TT. If any bike gave cause for concern near the limit, it was the YZF, especially when braking deep into third-gear Turn 1. When it began to fold under, though, the front end gave ample warning in the form of wheel hop. I also felt a hint of headshake when crossing a bump at the exit of the following third-gear sweeper. The other 600s, however, remained stable through this portion of the racetrack.

Shifting the high-revving Yamaha engine 1000 rpm short of redline delivered optimum power. The extra thousand rpm of over-rev worked quite nicely in a couple of sections, where remaining in the selected gear eliminated an upshift and an immediate downshift prior to entering the next corner. Once again, only the footpeg feelers touched down, even when tempting the limits of the street-compound Dunlop D207s. When 1 toggled through the stored laps afterward, the Unipro showed several laps in the :46s, with a best of 1:45.36.

By contrast, the ZX-6R’s steering felt slightly heavier, but with an increased sense of stability. Several riders noted how much easier it was to jump on this bike and lap quickly within a few circuits. Credit the Ninja’s broad spread of usable power. Cutting the quickest times still required maintaining 10,000-rpm-plus when possible. The exception-all bikes included-was when exiting the slowest corners of the circuit. Here, first gear was too low for a fluid entry and exit, yet second gear allowed the revs to fall below the 8000-rpm mark. Opting for the latter scenario least affected the Kawasaki. The D207s provided all the grip needed to regularly bury the footpegs-and the muffler less frequently-en route to a best lap time of 1:46.64.

Following two days of track-scratching madness came the long journey home. I was totally whipped from the intensity of saddle-hopping between the year’s best 600, 750, 900 and lOOOcc sportbikes. My butt was sore, my wrists ached and my mind was numb. And in this semi-conscious state, I found myself seeking the comfort and competence of Kawasaki’s supremely user-friendly ZX-6R.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Ten Rest, 2000

July 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Perfect Baja Bike

July 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCCounting Cracks

July 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

July 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupFriedel Münch Strikes Again

July 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupAprilia Buys Moto Guzzi

July 2000 By Bruno De Prato