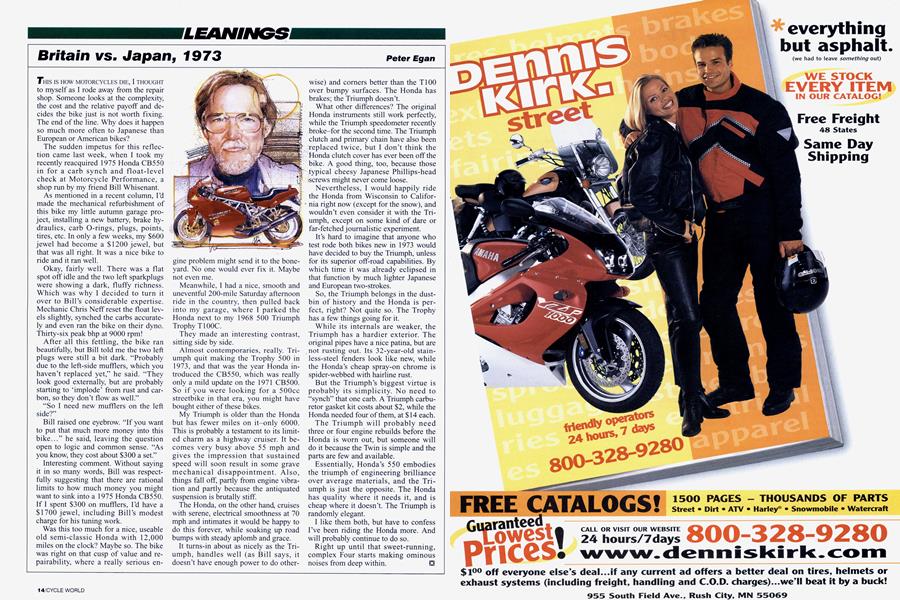

Britain vs. Japan, 1973

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

THIS IS HOW MOTORCYCLES DIE, I THOUGHT to myself as I rode away from the repair shop. Someone looks at the complexity, the cost and the relative payoff and decides the bike just is not worth fixing. The end of the line. Why does it happen so much more often to Japanese than European or American bikes?

The sudden impetus for this reflection came last week, when I took my recently reacquired 1975 Honda CB550 in for a carb synch and float-level check at Motorcycle Performance, a shop run by my friend Bill Whisenant.

As mentioned in a recent column, Ed made the mechanical refurbishment of this bike my little autumn garage project, installing a new battery, brake hydraulics, carb O-rings, plugs, points, tires, etc. In only a few weeks, my $600 jewel had become a $1200 jewel, but that was all right. It was a nice bike to ride and it ran well.

Okay, fairly well. There was a flat spot off idle and the two left sparkplugs were showing a dark, fluffy richness. Which was why I decided to turn it over to Bill’s considerable expertise. Mechanic Chris Neff reset the float levels slightly, synched the carbs accurately and even ran the bike on their dyno. Thirty-six peak bhp at 9000 rpm!

After all this fettling, the bike ran beautifully, but Bill told me the two left plugs were still a bit dark. “Probably due to the left-side mufflers, which you haven’t replaced yet,” he said. “They look good externally, but are probably starting to ‘implode’ from rust and carbon, so they don’t flow as well.”

“So I need new mufflers on the left side?”

Bill raised one eyebrow. “If you want to put that much more money into this bike...” he said, leaving the question open to logic and common sense. “As you know, they cost about $300 a set.”

Interesting comment. Without saying it in so many words, Bill was respectfully suggesting that there are rational limits to how much money you might want to sink into a 1975 Honda CB550. If I spent $300 on mufflers, I’d have a $1700 jewel, including Bill’s modest charge for his tuning work.

Was this too much for a nice, useable old semi-classic Honda with 12,000 miles on the clock? Maybe so. The bike was right on that cusp of value and repairability, where a really serious engine problem might send it to the boneyard. No one would ever fix it. Maybe not even me.

Meanwhile, I had a nice, smooth and uneventful 200-mile Saturday afternoon ride in the country, then pulled back into my garage, where I parked the Honda next to my 1968 500 Triumph Trophy T100C.

They made an interesting contrast, sitting side by side.

Almost contemporaries, really. Triumph quit making the Trophy 500 in 1973, and that was the year Honda introduced the CB550, which was really only a mild update on the 1971 CB500. So if you were looking for a 500cc streetbike in that era, you might have bought either of these bikes.

My Triumph is older than the Honda but has fewer miles on it-only 6000. This is probably a testament to its limited charm as a highway cruiser. It becomes very busy above 55 mph and gives the impression that sustained speed will soon result in some grave mechanical disappointment. Also, things fall off, partly from engine vibration and partly because the antiquated suspension is brutally stiff.

The Honda, on the other hand, cruises with serene, electrical smoothness at 70 mph and intimates it would be happy to do this forever, while soaking up road bumps with steady aplomb and grace.

It turns-in about as nicely as the Triumph, handles well (as Bill says, it doesn’t have enough power to do otherwise) and corners better than the T100 over bumpy surfaces. The Honda has brakes; the Triumph doesn’t.

What other differences? The original Honda instruments still work perfectly, while the Triumph speedometer recently broke-for the second time. The Triumph clutch and primary chain have also been replaced twice, but I don’t think the Honda clutch cover has ever been off the bike. A good thing, too, because those typical cheesy Japanese Phillips-head iscrews might never come loose.

Nevertheless, I would happily ride the Honda from Wisconsin to California right now (except for the snow), and wouldn’t even consider it with the Triumph, except on some kind of dare or far-fetched journalistic experiment.

It’s hard to imagine that anyone who test rode both bikes new in 1973 would have decided to buy the Triumph, unless for its superior off-road capabilities. By which time it was already eclipsed in that function by much lighter Japanese and European two-strokes.

So, the Triumph belongs in the dustbin of history and the Honda is perfect, right? Not quite so. The Trophy has a few things going for it.

While its internals are weaker, the Triumph has a hardier exterior. The original pipes have a nice patina, but are not rusting out. Its 32-year-old stainless-steel fenders look like new, while the Honda’s cheap spray-on chrome is spider-webbed with hairline rust.

But the Triumph’s biggest virtue is probably its simplicity. No need to “synch” that one carb. A Triumph carburetor gasket kit costs about $2, while the Honda needed four of them, at $ 14 each.

The Triumph will probably need three or four engine rebuilds before the Honda is worn out, but someone will do it because the Twin is simple and the parts are few and available.

Essentially, Honda’s 550 embodies the triumph of engineering brilliance over average materials, and the Triumph is just the opposite. The Honda has quality where it needs it, and is cheap where it doesn’t. The Triumph is randomly elegant.

I like them both, but have to confess I’ve been riding the Honda more. And will probably continue to do so.

Right up until that sweet-running, complex Four starts making ominous noises from deep within.