Sprint Special

CYCLE WORLD TEST

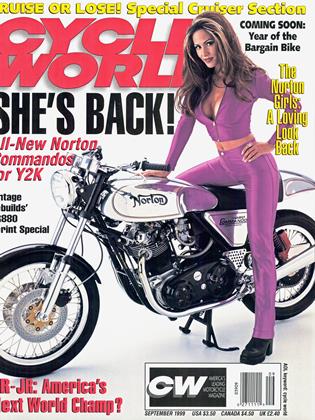

A Norton for the Nineties... and beyond

LONG AFTER NORTONS SHOULD HAVE been left on history’s junk pile, they endure, old enough now to draw Social Security. It’s been a quarter-century since the factory shuttered its doors, but Nortons not only persist, they thrive. And none more so than the hand-built hot-rods being turned out by Vintage Rebuilds, a small Oregon shop run by one Kenny Dreer.

Dreer, 51, is a man on a mission. What might have happened, he wondered, if Norton hadn’t been run into the ground by England’s nanny state business policies back in the 1970s? What would the next generation of Commandos been like?

His answer is the VR880 Sprint Special, a totally remanufactured Norton that uses 80 percent all-new parts. Even the Prince of Darkness has been all but exorcised-only two Lucas electrical components remain, the stator and the rotor, and those have been updated with the latest mod-cons.

Joining the Sprint Special in Vintage Rebuilds’ model line will be the mid-level Super Twin and a more traditional, drumbraked Clubman Classic. Geared up for small-scale production, Dreer hopes to sell 50 of his thoroughly modernized Nortons a year. One per state, that’s all he asks.

First of the 50 for year 2000 belongs to Pennsylvania investment broker Charlie Petitt, who kindly lent Cycle World his VR880 for this test, never mind that he had yet to see the finished bike!

Genesis of the 880 project began last year when Dreer put one of his souped Commando 850s on a dyno and was unhappy to see rear-wheel readings no higher than 54 bhp, with a severe case of asthma at 6000 rpm, 1000 revs short of redline. Back to the workbench. Cylinder heads were packed off to Baisley High Performance for some serious flow work. Besides working his Dremel tool magic on the intake and exhaust ports, Dan Baisley prescribed Kibblewhite Precision Machine valves, guides, springs and retainers, originally intended for go-fast duty in Kawasaki’s KZ1000. The Kawi valves have 7mm stems, down from the Stocker’s 7.9mm, which gives a double bonus of less reciprocating weight and less airflow obstruction. Baisley, well known in the Harley drag-race world, capped off his labor by sculpting the valve guides, again in an effort to streamline the intake draw and exhaust charge. A Mega Cycle 6000-series cam, high-lift and short duration for good midrange punch, opens and closes Baisley’s handiwork.

Pistons came next, proprietary items made for Vintage Rebuilds by JE. Increasing piston size to 79mm (up from 77 stock) yielded a full 880cc of displacement, but first the slug-makers at JE had to overcome the Commando’s curiously off-center combustion chambers, the result of the Norton Twin growing from a 500 in 1949 to a 650 to a 750 and then to an 850 (actually 828cc) in 1973. Stock 8.5:1 pistons were flat-topped, so the wonky offset was no big deal back then. But Dreer wanted to bump compression to 10.5:1, meaning that the necessary domed-dish had to be moved up and outboard on the piston top. After experimentation, Dreer settled on Total Seal rings, the middle a “gapless” design that uses an L-shaped primary ring with a thinner secondary ring, their end-gaps located 180 degrees apart.

Dreer didn’t have to go too far downstream to encounter his next logjam. The stock, l3/8-inch-diameter headpipes were undoing some of Baisley’s hardwon headwork. Salvation came in the form of D/2-inch headers, custom-bent to VR’s specs.

Standard-issue alloy con-rods go into the VR880, as does a stock crank, though it’s lightened by 2 pounds and rebalanced, and Dreer painstakingly blueprints the bottom-end clearances. Decidedly unstock is the left-side crankcase, usually the Achilles heel of any high-performance Norton-Ron Wood’s flat-track Commandos used to go into battle at Ascot with braids of external weld reinforcing the case. Dreer’s solution is more sanitary; cracks are kept at bay with a new, recast left-hand case up to an inch thick at the critical bearing wall.

Sparked by a Boyer-Brandsen electronic ignition and 30,000-volt Dyna dual-output coil, the VR880 snuggles right up to 70 rear-wheel horsepower with a stout 56 foot-pounds of torque. On its best day, a stock 850 Commando was lucky to get a whiff of 50 bhp and made a whopping 10 ft.-lbs. less torque.

Given its meaty torque curve and sub-400-pound dry weight, we expected the 880 to gallop into the low 12s at the dragstrip, with an outside shot of breaking into the 11s. Didn’t happen, which needs some explanation. Our usual test site, sea-level Carlsbad Raceway, was solidly booked, so with deadline rapidly descending we were forced to use a less-than-ideal location, altitude 2500 feet. Factor in unusually hot temperatures, and our data panel’s 12.57-sec./104.48-mph entry doesn’t quite paint a true picture of the Norton’s sprinting abilities. Figure an easy 12.3, maybe a tenth less, at Carlsbad, with a 108to 110-mph terminal says Our Man of the Bleach Box, “Dyno” Don Canet. Real whiplash fiends can order their 880 with a 19-

tooth countershaft sprocket (ours was running a relatively tall 21 teeth), which should place the bike solidly at the 11second door.

Much more impressive, though, is the Sprint Special’s performance out on the open road. We lugged the Norton through the stop-n-go gamut of beach traffic, ran it hard in the hills, hammered it in 100-degree desert heat and buzzed it down the interstate, in all a total of 500 miles, much of it between an indicated 70 and 80 per. It never pinged, never cooked its clutch and save for a

small dribble of Mobil 1 Synthetic from a banjo fitting (well, it is British), didn’t use a drop of oil.

Our only mechanical problem was a broken clutch cable, for which Dreer flogged himself mercilessly. Power was right-now immediate, all the way from 2500 ipm in top gear to redline and just beyond, good for 127 mph.

Aiding immensely with the VR880’s ridability is its driveline, one of the smoothest and snatch-free we’ve encountered on any motorcycle. Start with the primary drive. Gone is the old oil-bathed triplex

chain, replaced with a 30mm Gates belt, which means the clutch (fortified with Barnett carbon-graphite plates) can run dry, and Dreer gets to dress up the trademark Commando primary cover with a series of large milled holes. The belt takes a set after the first 50 miles and usually needs no further adjustment; replacement is called for every 30,000 miles/4 years. Middleman in the driveline is the positively Victorian four-speed gearbox, separate from the engine and operated with the right boot, just as the Queen intended.

Old it may be, but the transmission shifts beautifully with solid, precise, satisfying snicks. Final players in getting the 880’s ponies to the pavement are an RK #520 O-ring chain and a very trick, three-piece cush sprocket. The latter was developed by drag-racer Ricky Crouch for mega-power Pro Stockers and is manufactured by Oklahoma’s Certco Industries, the aerospace firm where he’s employed. It all works wonderfully well; there are more than a few modem machines that could take lessons from this Norton when it comes to driveline lash.

Almost as armor-plated as the

engine/driveline is the Norton's chassis. Before being sent off for straightening, realigning and black powdercoat, each VR frame gets a crossbrace welded between the two thin front downtubes to prevent “walking” under load. Also added is a fourth rubber engine mount, dubbed “Quadra-lastic” by Dreer and crew. Norton’s original, three-point Isolastic mounting system, introduced in 1969, gave the old, vibration-intense parallel-Twin a new lease on life. Steel plates joined the engine, gearbox and swingarm into one sub-assembly, which attached to the main frame via thick rubber mounts. The mounts allowed the assembly to move up and down fairly freely, while a system of shims-later vernier adjusters-kept side clearances, obviously critical to good handling, to within .010-inch. By all accounts, the system was a good one, especially above 3000 rpm where the bike became glassy smooth, and handling didn’t seem to suffer despite the rub ber-mounted swingarm.

Dreer was worried, though, that his VR880s, making 20 more horsepower and wearing stickier rubber, would tax the frame. Hence the fourth mount, located beneath the motor/gearbox. The one draw back is increased vibration felt at the handlebar and through the knurledaluminum footpegs.

Anchored by its beefed-up frame, we firmly believe the Sprint Special will be an impeccable, pinpoint handler, but as delivered our testbike had problems. First, the Paioli piggyback shocks, which certainly look the part, gave up any semblance of damping before we hit our first set of curves. Second, the fork is still a work in progress. In a bold move, Dreer has adapted Honda CBR600F3 cartridge internals, adjustable for spring preload and rebound damping, to the Norton Roadholder fork. But hung up by vendors and pressed by our test schedule, he had to go with modified stock springs that just weren’t up to the task, too stiff to respond to small irregularities, yet coil-binding after 4 inches of travel.

We whipped on a set of non-reservoir Paiolis to continue testing, and on smooth pavement the VR’s manners were flawless, the wide handlebar and skinny, 19-inch Avon combining to give the kind of accurate turn-in and easy steering that today’s clip-onequipped, monster-weenied sportbikes can’t match, albeit their performance envelope is much, much wider. Dreer is right now in serious discussion with Paioli about its shocks (may we suggest something more modern?) and already has suspension specialists RaceTech lined up to fix the forks.

More successful are the 880’s triple disc brakes, developed for Vintage Rebuilds by Kosman Engineering, which custom-made the hubs and great-looking floating rotors, then adapted single-piston GMA calipers, Harley aftermarket items. Supplying the front brake fluid through braidedsteel lines is a Magura master cylinder that wears a BMW parts number; a Grimeca master cylinder resides out back. The setup is not suitable for Kevin Schwantz-type late-braking antics, granted, but it is a full generation ahead of the stock binders. A very tidy application, though perfectionist Dreer wants to experiment with softer pad compounds up front for better feel.

At $20,000-plus, Vintage Rebuilds’ VR880 Sprint Special ain’t for everyone. Dreer is after a few good men who don’t mind kickstarting a big-bore Twin to life. Who revel in a rorty, unbridled exhaust note. Who get moist at the sight of stainless-steel hardware. Who appreciate dedicated craftsmanship. Who want something different. And who want the finest Nortons ever made. □

NORTON VR880

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Teabag Chronicles

September 1999 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsSlow Seduction

September 1999 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCSubject To Change

September 1999 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 1999 -

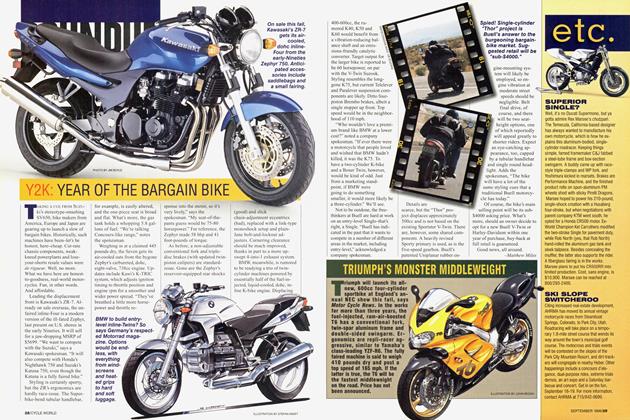

Roundup

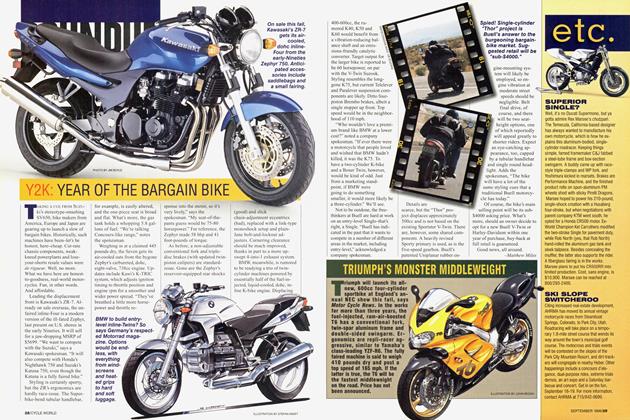

RoundupY2k: Year of the Bargain Bike

September 1999 -

Roundup

RoundupTriumph's Monster Middleweight

September 1999