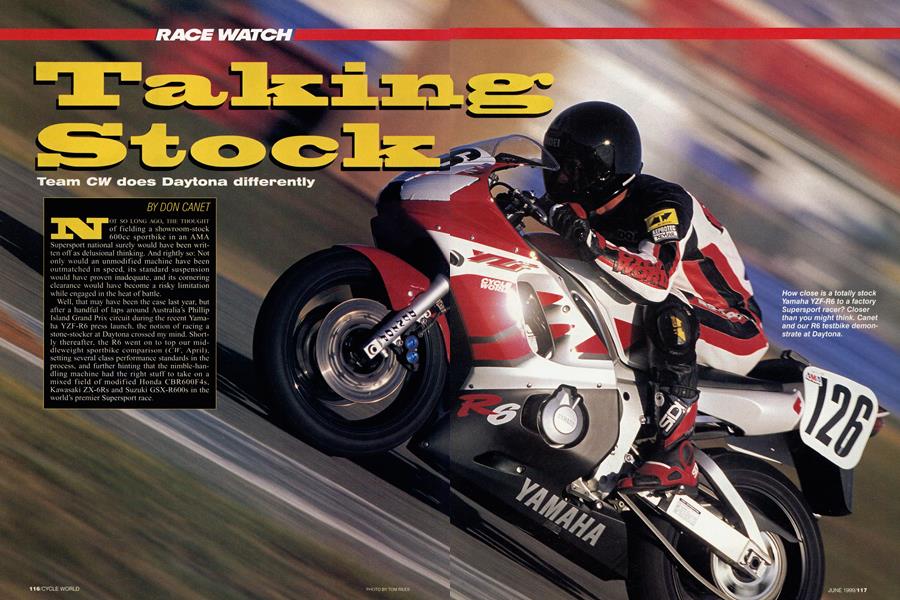

Taking Stock

RACE WATCH

Team CW does Daytona differently

DON CANET

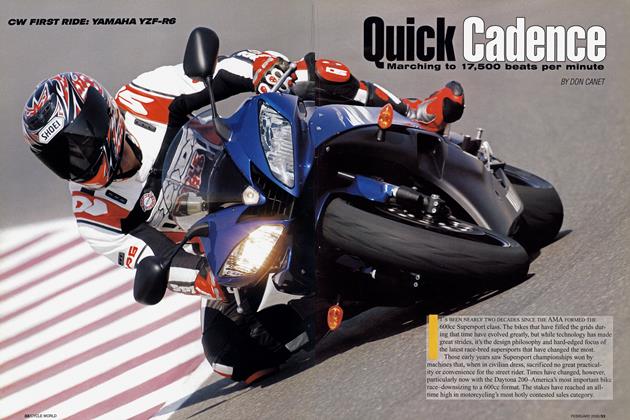

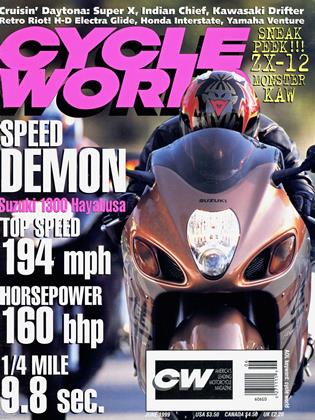

NOT SO LONG AGO, THE THOUGHT of fielding a showroom-stock 600cc sportbike in an AMA Supersport national surely would have been written off as delusional thinking. And rightly so: Not only would an unmodified machine have been outmatched in speed, its standard suspension would have proven inadequate, and its cornering clearance would have become a risky limitation while engaged in the heat of battle. Well, that may have been the case last year, but after a handful of laps around Australia’s Phillip Island Grand Prix circuit during the recent Yamaha YZF-R6 press launch, the notion of racing a stone-stocker at Daytona crossed my mind. Shortly thereafter, the R6 went on to top our middleweight sportbike comparison (CW, April), setting several class performance standards in the process, and further hinting that the nimble-handling machine had the right stuff to take on a mixed field of modified Honda CBR600F4s, Kawasaki ZX-6Rs and Suzuki GSX-R600s in the world's premier Supersport race.

So, rather than perform the usual host of Supersport racing mods allowed by the AMA rulebook, we sought to see how well the standard street package would fare against top-level opposition. Think of it as the ultimate follow-up to our comparison test.

To properly set the stage, it must be noted that the AMA 600cc Supersport class is an intense battleground hotly contested by the Japanese Big Four. This year’s Daytona 600 field was no exception, featuring more than a dozen full-factory bikes ridden by many of the same stars who headline AMA Superbike racing. Reinforcing this impressive armada were several additional bike/rider combos fielded by factory support teams. Obviously, a podium finish for our R6 was about as likely as a ban on beer during Bike Week. My realistic goal would be to crack into the top 35 and cut sub-2minute lap times along the way. .

While the competition undoubtedly spent countless hours preparing their bikes for the season opener, I invested little more than an afternoon prepping the R6 in the CW shop. Savvy supersport tuners tweak such things as cam timing, spark advance and carburetor jetting.

They perform the perfect valve job and experiment with various tuned exhaust systems. I changed my bike’s oil, and removed the turnsignals, mirrors and passenger pegs. The headlight, taillight and horn were each unplugged, but remained onboard. The oil drain plug and filler cap were safety wired-surprisingly, the only wiring AMA tech requires these days. A Diet Coke can secured to the frame with zip ties served as the rules-mandated heat-resistant catch container for vent and overflow hoses. A sheet of ABS plastic was siliconed into the fairing lower to close off its large opening, thus meeting the tech requirement for a 3-quart catch basin-the idea of which is to keep oil from dumping onto the track in the event a broken conrod punches a hole though the engine case. Adhesive numberplates applied, my bike hitched a ride with a truckload of Royal Star demo

bikes headed for Florida.

I arrived at Daytona International Speedway two days before the race for the first official practice. Unfortunately, my bike wasn’t waiting in the garage area as per the plan. By the time I tracked down the R6-safely tucked away in a Yamaha semitrailer outside the track-rode it back to the infield paddock, unbolted the sidestand and haggled with the AMA tech inspectors over the placement of my side numberplates, the morning 600 practice was nearly over. I completed a single lap before receiving the checkered flag signaling the session’s end.

In a sense I had been saved by the bell, as it was one of the hairiest laps I’ve ever experienced. Not only was this my first look at the course since I last raced here in ’96 aboard a Kinko’s Kawasaki ZX7R, but my tires were stone-cold while most everyone else was already up to speed. Guys zipped past left and right as I tip-toed around the track trying to stay clear of the racing line.

Chuck Graves Motorsports-a Yamaha factory support team out of Van Nuys, California-took me under its wing. I pitted outside Graves’ paddock garage and borrowed a tool or two when needed. For a chuckle and convenience, I did a bit of wrenching using the stock tool kit found under the R6’s seat. Perhaps I was taking the stock-racer concept a bit too far? There were, however, two concessions I allowed for safety’s sake: First, a set of race-compound Dunlop D207 Sportmax II GP radiais was mounted in place of the OEM street-compound D207s. And second, a Scotts steering-damper kit (available through Graves Motorsports, 818/902-1942) was mounted on the top triple-clamp to quell headshake experienced in Daytona’s rather bumpy Chicane.

Running a high line on the speedway’s famous banking is an experience unlike any other. With its 160-mph top-speed potential, our stock R6 fulfilled my need for speed, and produced enough g-forces in the bowl to pin my chest onto the fuel tank. The stocker surprised a number of unsuspecting racers as I drove past on the banking with little more than a whisper coming from the stock muffler. Not only was I riding the quietest bike on the track, but I had the only rear fender hanging from its tail. For a bit of good-natured humor, CWs Assistant Art Director Brad Zerbel created a mock California license plate that read “STOCKER,” and this was pasted to the fender.

And stock it was, right down to the gearing, carburetor jetting and suspension. Without the aid of Daytona’s famous draft, the rev-counter would reach 14,300 rpm in top gear at the fastest parts of the track. Tucking into another bike’s slipstream on the banking was often good for an additional 500-1000 rpm. There were times in

practice when I ducked into the draft of a factory bike as it passed me in the bowl, and was actually able to gain ground. It became evident, however,

that even the better privateer machines enjoyed an acceleration advantage off the infield corners.

I seemed to suffer the most driving out of the International Horseshoe, as first gear was too low and second gear was on the tall side. I opted to run

through the tight right-hander in second, even though the revs would fall below 9000 rpm, making for a soft drive off the corner.

By the time Thursday’s qualifying session came around, I had settled on suspension settings that I would use in Friday’s race. Shock spring preload was bumped all the way up to its seventh step on the ramp, while rebound was set at five clicks out from maximum, and compression was set at four clicks out. Compression and rebound damping in the fork also were set at four clicks out, while preload was set with four lines showing on the adjuster. The fork legs were pulled up through the clamps 10mm to compensate for the taller-thanstock 70-series front tire.

With a fresh rear Dunlop mounted,

I kept my head down during the 20minute qualifying session. A rider’s fastest lap is used to determine placement on the starting grid, and 1 wound up 32nd quickest of the 58 riders, with a time of 2:00.87. As a result, I was seeded on the eighth row for the 18-lap race.

Daytona starts are crazier than most other tracks. The grid is set on the hot pit lane, and when the green flag flies, the pack enters Turn 1 from the end of the lane. The corner, however, is totally unfamiliar to the riders, as we used a different pit out throughout practice and qualifying. Imagine running elbow-to-elbow amid a huge gaggle of bikes into a turn you’ve never ridden through before. There was a lot of bobbing and weaving going on, and I nearly got pushed off into the grass. The entire first lap entailed defensive-riding tactics as traffic backed up at both infield horseshoes and the Chicane. It was like Bike Week traffic on Main Street, but without the traffic cops to uphold the appearance of order. While I saw an opportunity to sneak up the inside and snatch a few positions, I chose to play it safe to avoid writing the dreaded “short story.”

It wasn’t long before the field had spread out and divided itself into several distinct clusters of combatants. Flogging the R6 for all it was worth, I clung to the tail end of a six-pack outside the top 20. Sweeping through the Chicane and onto the East Banking, I found myself being towed by the biggest draft I’d caught all week. Coming off NASCAR Turn 4 onto the finish straight, the air pocket created by the bikes ahead tractor-beamed my stealthy steed smack into its 15,500rpm rev-limiter. Flashing through the Tri-Oval, the YZF’s digital speedometer momentarily registered an indicated 181 mph as I bent it into the left-hand curve. It then settled back to 177 mph as the cornering force scrubbed away some speed.

My amazement quickly turned to shock, however, as I applied the front brakes for Turn 1. The lever came all the way back to the grip, requiring a quick double-pump to get the pads to bite the rotors with enough force to slow for the second-gear corner ahead. Yee-ow! That’s much too close for comfort when you’re tailgating other riders. The brake problem was caused by a bit of headshake I’d experienced through the right-toleft transition exiting the Chicane. The flex induced by the bar-swapper had pushed the pads back away from the rotors. From that point on, I fingered the lever each lap following the Chicane just to be sure.

Through all the distraction and drama I lost touch with the six-pack, and rode much of the race all alone. In the final laps, I caught and passed a GSX-R600-mounted straggler from the group ahead and crossed the line in 27th place, having dipped into the 1:59s. To give some perspective, the race leaders

ran 1:56s, and my fastest lap in ’96 on a fully race-prepped 750cc Supersport bike was a 1:57. Furthermore, the rear shock maintained a consistent level of damping control throughout the race, and the stock exhaust canister only skimmed the tarmac a few times.

Overall, my Daytona experience was a fun-filled way of “taking stock” and assessing the performance of today’s street-going supersports. It goes to show just how capable sportbikes have become.

Up ahead, a titanic multi-rider battle for the lead had boiled down to a photo finish. The factory Yamaha of Jamie Hacking took third, narrowly escaping a collision with the Honda of wildly weaving winner Miguel Duhamel at the stripe. Kenny Roberts’ youngest son Kurtis finished a close second on an Erion Racing F4. As I watched the televised rerun from the safety of my sofa back home, I had no regrets to have been well clear of that action. After all, the license plate frame on my R6 said it all: “My bike’s stock, what’s your excuse?”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue