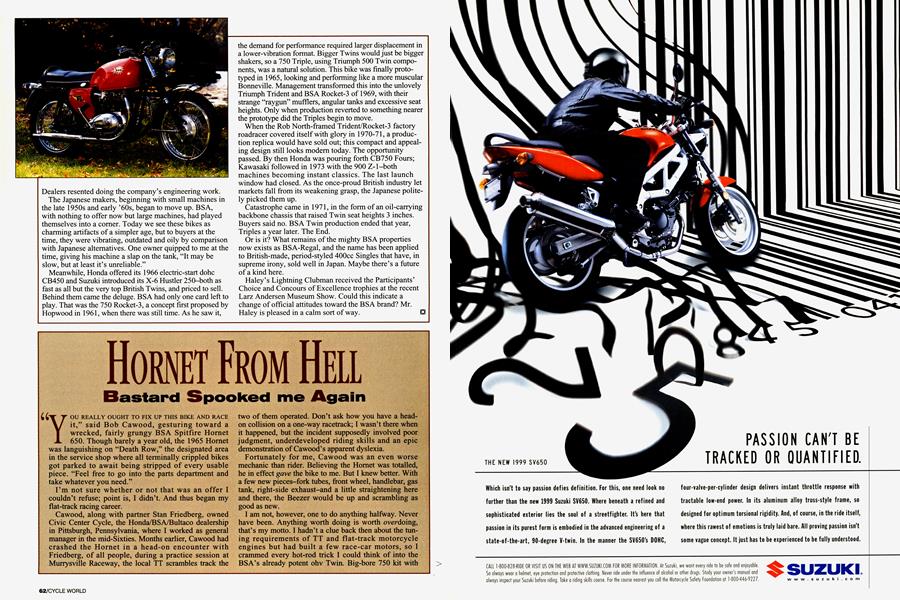

HORNET FROM HELL

Bastard Spooked me Again

YOU REALLY OUGHT TO FIX UP THIS BIKE AND RACE it," said Bob Cawood, gesturing toward a wrecked, fairly grungy BSA Spitfire Hornet 650. Though barely a year old, the 1965 Hornet was languishing on “Death Row,” the designated area in the service shop where all terminally crippled bikes got parked to await being stripped of every usable piece. “Feel free to go into the parts department and take whatever you need.”

I’m not sure whether or not that was an offer I couldn’t refuse; point is, I didn’t. And thus began my flat-track racing career.

Cawood, along with partner Stan Friedberg, owned Civic Center Cycle, the Honda/BSA/Bultaco dealership in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where I worked as general manager in the mid-Sixties. Months earlier, Cawood had crashed the Hornet in a head-on encounter with Friedberg, of all people, during a practice session at Murrysville Raceway, the local TT scrambles track the two of them operated. Don’t ask how you have a headon collision on a one-way racetrack; I wasn’t there when it happened, but the incident supposedly involved poor judgment, underdeveloped riding skills and an epic demonstration of Cawood’s apparent dyslexia.

Fortunately for me, Cawood was an even worse mechanic than rider. Believing the Hornet was totalled, he in effect gave the bike to me. But I knew better. With a few new pieces-fork tubes, front wheel, handlebar, gas tank, right-side exhaust-and a little straightening here and there, the Beezer would be up and scrambling as good as new.

I am not, however, one to do anything halfway. Never have been. Anything worth doing is worth overdoing, that’s my motto. I hadn’t a clue back then about the tuning requirements of TT and flat-track motorcycle engines but had built a few race-car motors, so I crammed every hot-rod trick I could think of into the BSA’s already potent ohv Twin. Big-bore 750 kit with 12.5:1 pistons. The highest lift, longest-duration cam I could lay my hands on. Oversized valves in ports the size of the Lincoln Tunnel. Cavernous, remote-float Amal GP carburetors. A flywheel with 40 percent of its mass winning BSA factory roadracer.

Neither did the chassis escape the wrath of my modification binge. A Ceriani fork was mated with a lightweight, alloy front wheel from a Bultaco 250 Métissé. The stock rear subframe, bent in Cawood’s crash, was replaced with a 4130 chrome-moly steel replica fabricated by a buddy who built race cars. Final touches included gold metalflake tank paint, a nifty Bates racing seat and fessionall painted numberplates that had my number, 44, highlighted with ultra-cool drop-shadows.

At the start of the season, then, I showed up with the trickest, slickest, most potent racebike that anyone in the Western Pennsylvania Motorcycle Racing Association had ever seen.

What I didn’t show up with, however, was even one lap of experience in any kind of motorcycle racing. I had logged a lot of seat time in race cars, but all that appeared on my two-wheel résumé were quite a few miles of street riding and a couple of brief forays into the woods on a Triumph Tiger Cub. Yet there I was, making my competition debut on an Open-class warhead better suited to Top Fuel drag racing than amateur dirt-tracking.

The outcome was not pretty. I had bombed the BSA’s engine not only to within an inch of its life, but to within an inch of mine, as well. Every time I cracked open the throttle, ol’ No. 44 would either fishtail uncontrollably or launch into a diabolical wheelie, all while throwing a roost that could stop a rampaging T-Rex in its tracks. As a consequence, I had to tippy-toe around comers like on

glare ice before even attempting to unleash the furious, all-or-nothing horsepower of the grossly overbuilt engine.

Through most of my first season, I led the league in last-place finishes. Because of my inexperience, I fully expected that I wouldn’t be able to run with the big dogs, but I started getting discouraged anyway. It was pretty embarrassing to show up at every event with the most extraval the field and consistently bring it last.

After watching me engage in hand-to-hand combat with my racebike every weekend, the local hotshoe with a name Hollywood would love, Baron Stutz Poser, asked if he could try my BSA in practice. I agreed, of course. I hoped that watching him make good use of my obviously superior race machine could help me learn how to cope with it.

To my great surprise, Poser didn’t circulate the fast TT course as quickly as he had on his own BSA 650 Hornet-which was bone-stock. And when he arrived back at my pit, he was ashen-faced. As he slowly shook his head back and forth in disbelief, he said, “How the

hell do you ride that f_____g thing? Jeezus, man, you’ve

gotta calm the motor down.”

Heeding Poser’s less-than-subtle advice, I slowly and gradually detuned the Hornet. Smaller carbs came first, then a milder cam. Lower compression followed shortly thereafter, as did pipes tuned for midrange rather than top end. And to no one’s surprise but mine, I got noticeably faster with each reduction in performance. By season’s end, I even started to earn some top-three finishes.

I didn’t win my first race until the following year. By then, the Hornet was much closer to stock-except for displacement-than to the ill-tempered, user-unfriendly beast it had been when it first hit the track.

I learned a lot of valuable lessons through all of this. One of them was that in the 650 Spitfire Hornet, BSA had built a pretty decent flat-track bike right out of the box. Only through my naivete and inexperience was it rendered the most wicked, evil, mean and nasty BSA dirt-tracker that ever turned a wheel.

God, I loved that bike.

-Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

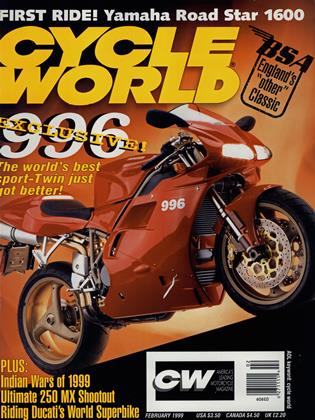

Up Front

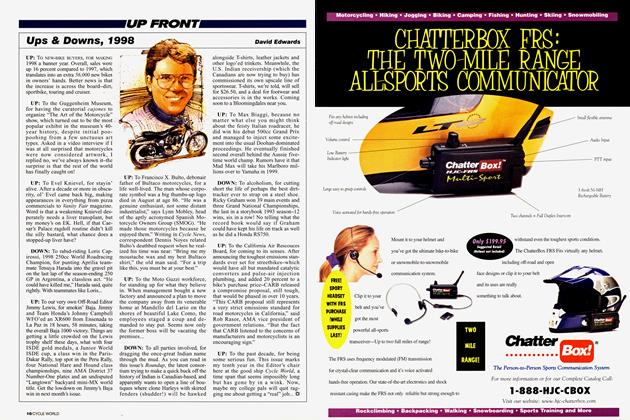

Up FrontUps & Downs, 1998

February 1999 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Great Book Explosion

February 1999 By Peter Egan -

TDC

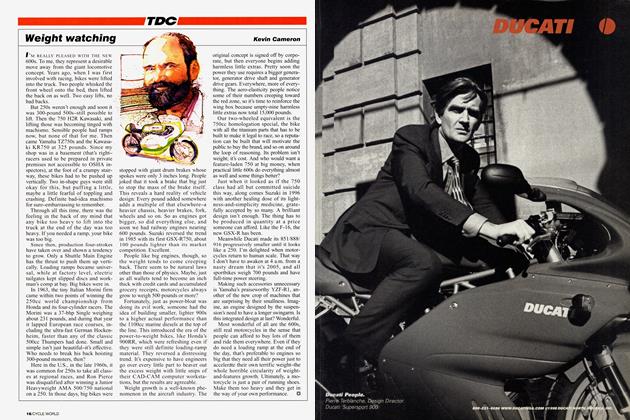

TDCWeight Watching

February 1999 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1999 -

Roundup

RoundupIndian Wars of 1999

February 1999 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupRadd Wigwam Racer?

February 1999 By Nick Lenatsch