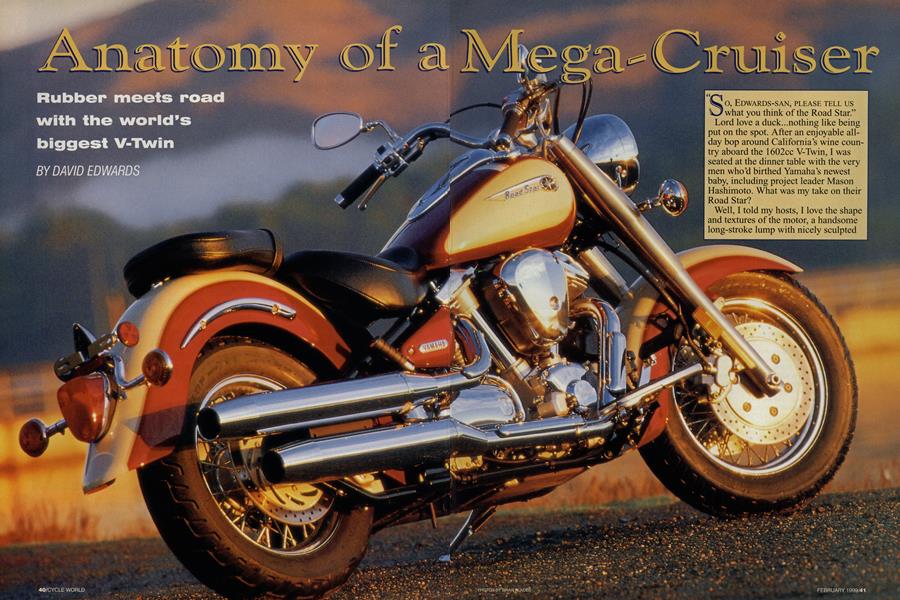

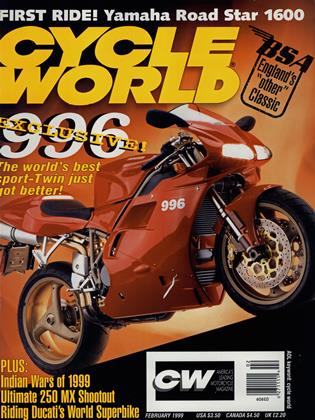

Anatomy of a Mega-Cruiser

Rubber meets road with the world’s biggest V-Twin

DAVID EDWARDS

SO, EDWARDS-SAN, PLEASE TELL US what you think of the Road Star."

Lord love a duck...nothing like being put on the spot. After an enjoyable all-day bop around California’s wine country aboard the 1602cc V-Twin, I was seated at the dinner table with the very men who’d birthed Yamaha’s newest baby, including project leader Mason Hashimoto. What was my take on their Road Star?

Well, I told my hosts, I love the shape and textures of the motor, a handsome long-stroke lump with nicely sculpted finning set off by chromed pushrod tubes and beveled rockerboxes, part H-D Shovelhead, part WWI1 Wright Cyclone. The plot gets a little lost on the left side of the engine, what with a fuel pump, cheesy plastic horns, various cables and rods, and the requisite pollution paraphernalia running to and fro mucking things up. Let’s not even mention the countershaft pulley cover, apparently lifted from the $1 discount bin at Pep Boys. Overall, though, a nice piece, an inviting engine.

“And how did you find the power?”

he glib reply is that I didn’t. For a more complete answer, scroll back several months to a meeting room at Yamaha’s U.S. headquarters, where I’d been invited for a confidential sneak peek at the Road Star. Before I was shown the bike, an overview complete with slide show: This was to be a “No Compromises” approach to building a cruiser, I was told. What the R1 was to sportbikes, what the YZ400F was to dirt Thumpers, the Road Star would be to cruisers. No other V-Twin would have more displacement or make more torque. While this was being explained, images were flashed on screen, old motorcycles the engineers used as inspiration-J.A.P.-engined Broughs, ancient Indians and, lastly, a Crocker V-Twin, the L.A.-built factory hot-rod that blew off all comers in its day.

Hot damn, I thought, these guys are really gonna kick some cruiser ass.

The pre-production Road Star I viewed was no bobbed-fender Crocker; instead, its styling was derivative of the Royal Star V-Four.

In silhouette, the two are very much alike. Closer inspection reveals the new bike to be the better unit, more cleanly done, with wire wheels, formal cylinder fins and a minimum of oxymoronic “beauty panels.” A 30-mile spin followed, during which it became clear that the Star’s 98-cubic-inch powerplant was more mainstreammodest than mountain-motor. In short, a nice bike, but not the asphalt-clawing brute I was led to believe. Ditto the production bike I rode at the U.S. press intro. The claim is 99 foot-pounds of torque and crankshaft horsepower “in the mid-60s.” Seat of the pants, I’d say that maybe 50 ponies make their way to the rear tire. The Twin’s power pulses are pleasing, thanks to a 45-pound crank assembly spinning away inside the cases, but this is no locomotive. It certainly ain’t a revver, either-redline is set at 4400 rpm, with the rev limiter dousing flames a few rpm higher. Why the mild tune and why four-valve heads for such a low-revving motor, I wondered.

My dinner partners, after much discussion in Japanese, offered, “This engine has much potential.” Of course, the next question, which I discreetly kept to myself, is then why didn’t you uncork the blasted thing and let it yodel?

ome thoughts on the subject: Remember that work on the Road Star began four years ago, when the Japanese were first getting a handle on the mega-cruiser concept.

At that time, the thinking (flawed in my humble opinion) was that the average cruiser buyer was not interested in performance-in fact, too much of it might scare him away. For evidence, Yamaha and others pointed to Harley-Davidson, selling all the underpowered, old-fashioned bikes it could build-and then some, with waiting lists for the most popular models. What wasn’t taken into consideration was that virtually all Harleys are modified to make more power, the parts plucked from aftermarket catalogs thick as bibles. That kind of support was not forthcoming for Japanese cruisers, so when the time came to soup up your Royal Star, say, you were pretty much s.o.l.-or had to spend so much money on components that a custom Hog began to look like a good proposition.

Bit of the old glass-ceiling syndrome going on here, too, in that the Royal Star is stuck at 65 or so rear-wheel bhp, and it wouldn’t do to have the new V-Twin making equal power, especially as it costs $3500 less than the V-Four. Still, cruiser horsepower is becoming much more of a sales issue. Ironically, Harley’s impressive new Twin Cam 88 motor is now the most potent of the big-bore V-Twins, pumping out 62 rear-wheel bhp, with more on tap from factory (as in warrantied) power-up kits. The Road Star, packing an extra 150cc but churning out something like 10-12 fewer horsepower, looks a little anemic by comparison.

But stances there in are the mitigating Road Star’s circumfavor. The first is price. At $10,500, the 1600 is priced to move, on par with Kawasaki’s 1500 Vulcan Classic, the best-selling of the big Japanese cruisers. Both are fat-fendered retros, but the Yamaha gets the styling nod by virtue of its crisper lines and better-looking engine.

Next saving grace is the Star’s “customability.” This is one Japanese cruiser the aftermarket should flock to. Belt-driven while most of its competitors use shaft final drive, the 1600 is a natural for billet wheels and rear pullies. There’s no radiator to camouflage. Unlike the Royal Star, its hardtail-look frame is fairly conventional, with no goofy seat pedestal to style around. Mufflers unbolt at the headpipes so healthier-sounding pipes are an easy add-on. Yamaha itself has more than 160 Star Line accessories already cataloged.

Performance pieces are in the pipeline, too, with at least one company hard at work on high-comp pistons (stock ratio is a humble 8.3:1), cams, carb kits, etc. Essential will be a different ignition box with a higher redline. Rear-wheel readings in the mid-70s should be a piece of cake, says an insider, which is more like it.

n the end, ironically, the No Compromises Company has turned out a compromised cruiser that needs the aftermarket’s help to reach its true potential-which, again ironically, may be the characteristic that draws buyers in. It’s worked before. Little company out of Milwaukee. You may have heard of it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontUps & Downs, 1998

February 1999 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Great Book Explosion

February 1999 By Peter Egan -

TDC

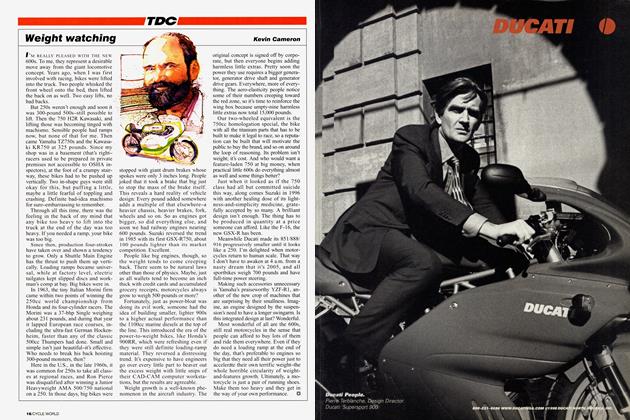

TDCWeight Watching

February 1999 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1999 -

Roundup

RoundupIndian Wars of 1999

February 1999 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupRadd Wigwam Racer?

February 1999 By Nick Lenatsch