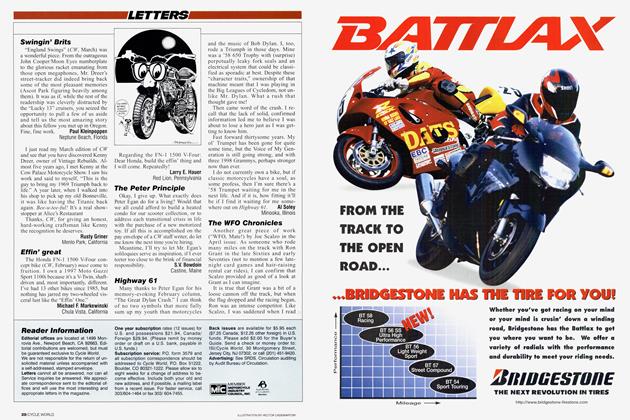

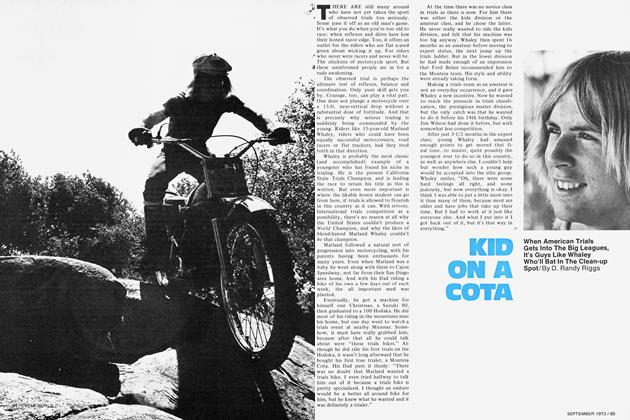

FAVE RAVE

In which we ask the not-so-simple question, "What’s your favorite bike?"

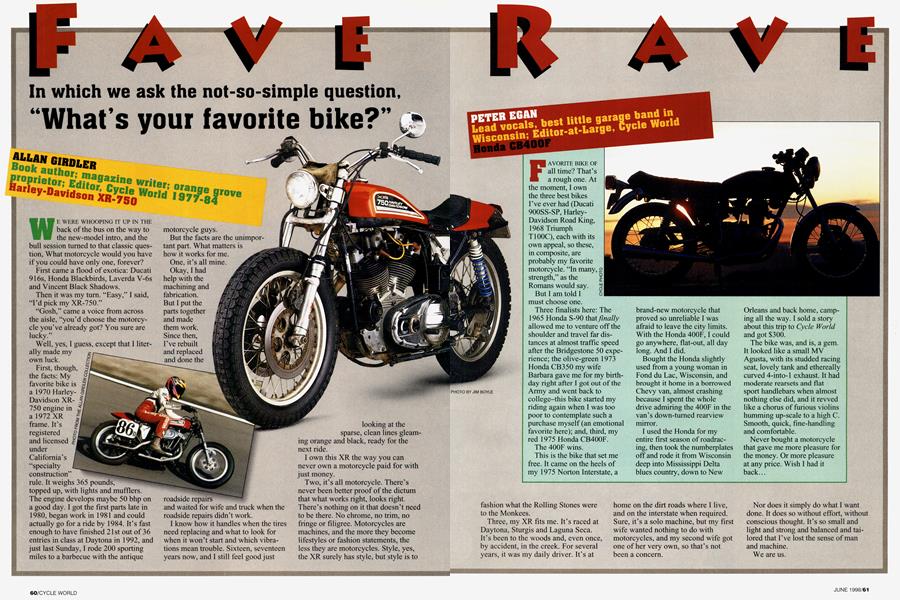

ALLAN GIRDLER Jook alw?or; r agazine Writer; orange grove Dlrietoi'; EdItor, Cvc~e World 1977-84 .~Har1ey~Davidson XR-750 1.

WE WERE WHOOPING IT UP IN THE back of the bus on the way to the new-model intro, and the bull session turned to that classic question, What motorcycle would you have if you could have only one, forever?

First came a flood of exotica: Ducati 916s, Honda Blackbirds, Laverda V-6s and Vincent Black Shadows.

Then it was my tum. “Easy,” I said, “I’d pick my XR-750.”

“Gosh,” came a voice from across the aisle, “you’d choose the motorcycle you’ve already got? You sure are lucky.”

Well, yes, I guess, except that I literally made my own luck.

First, though, the facts: My favorite bike is a 1970 HarleyDavidson XR3 750 engine in a 1972 XR frame. It’s registered and licensed under

California’s “specialty construction’ rule. It weighs 365 pounds, topped up, with lights and mufflers. The engine develops maybe 50 bhp on a good day. I got the first parts late in 1980, began work in 1981 and could actually go for a ride by 1984. It’s fast enough to have finished 21 st out of 36 entries in class at Daytona in 1992, and just last Sunday, I rode 200 sporting miles to a barbecue with the antique motorcycle guys.

But the facts are the unimportant part. What matters is how it works for me.

One, it’s all mine.

Okay, I had help with the machining and fabrication.

But I put the parts together and made them work. Since then, I’ve rebuilt and replaced and done the roadside repairs and waited for wife and truck when the roadside repairs didn’t work.

I know how it handles when the tires need replacing and what to look for when it won’t start and which vibrations mean trouble. Sixteen, seventeen years now, and 1 still feel good just looking at the sparse, clean lines gleaming orange and black, ready for the next ride.

I own this XR the way you can never own a motorcycle paid for with just money.

Two, it’s all motorcycle. There’s never been better proof of the dictum that what works right, looks right. There’s nothing on it that doesn’t need to be there. No chrome, no trim, no fringe or filigree. Motorcycles are machines, and the more they become lifestyles or fashion statements, the less they are motorcycles. Style, yes, the XR surely has style, but style is to fashion what the Rolling Stones were to the Monkees.

little gala e band in ycIe Woild

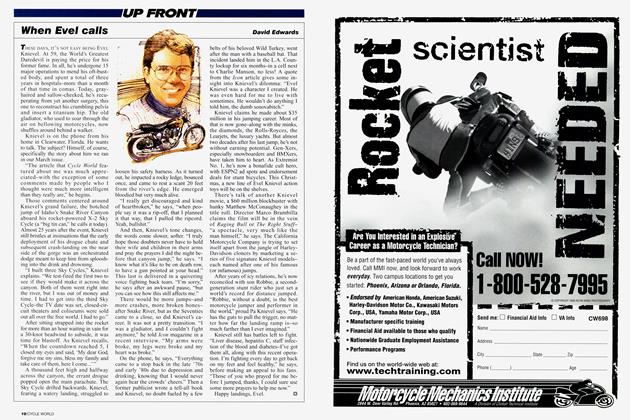

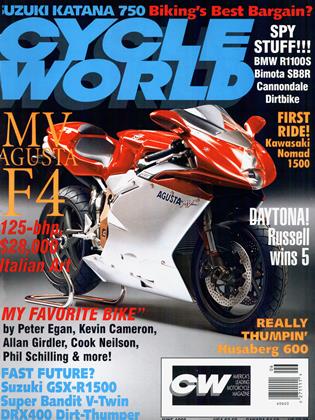

FAVORITE BIKE OF all time? That’s a rough one. At the moment, I own the three best bikes I’ve ever had (Ducati 900SS-SP, HarleyDavidson Road King, 1968 Triumph T100C), each with its own appeal, so these, in composite, are probably my favorite motorcycle. “In many, ° strength,” as the | Romans would say. g

But lam told I must choose one.

Three finalists here: The 1965 Honda S-90 that finally allowed me to venture off the shoulder and travel far dis tances at almost traffic speed after the Bridgestone 50 expe rience; the olive-green 1973 Honda CB350 my wife Barbara gave me for my birth day right after I got out of the Army and went back to college-this bike started my riding again when I was too poor to contemplate such a purchase myself (an emotional favorite here); and, third, my red 1975 Honda CB400F.

The 400F wins.

This is the bike that set me free. It came on the heels of my 1975 Norton Interstate, a brand-new motorcycle that proved so unreliable I was afraid to leave the city limits. With the Honda 400F, I could go anywhere, flat-out, all day long. And I did.

Bought the Honda slightly used from a young woman in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, and brought it home in a borrowed Chevy van, almost crashing because I spent the whole drive admiring the 400F in the van’s down-turned rearview mirror.

I used the Honda for my entire first season of roadracing, then took the numberplates off and rode it from Wisconsin deep into Mississippi Delta blues country, down to New Orleans and back home, camping all the way. I sold a story about this trip to Cycle World and got $300.

The bike was, and is, a gem. It looked like a small MV Agusta, with its studded racing seat, lovely tank and ethereally curved 4-into-1 exhaust. It had moderate rearsets and flat sport handlebars when almost nothing else did, and it revved like a chorus of furious violins humming up-scale to a high C. Smooth, quick, fine-handling and comfortable.

Never bought a motorcycle that gave me more pleasure for the money. Or more pleasure at any price. Wish I had it back...

Three, my XR fits me. It’s raced at Daytona, Sturgis and Laguna Seca. It’s been to the woods and, even once, by accident, in the creek. For several years, it was my daily driver. It’s at

home on the dirt roads where l live, and on the interstate when required. Sure, it’s a solo machine, but my first wife wanted nothing to do with motorcycles, and my second wife got one of her very own, so that’s not been a concern.

Nor does it simply do what I want done. It does so without effort, without conscious thought. It’s so small and light and strong and balanced and tailored that I’ve lost the sense of man and machine.

We are us.

KEVIN CAMERON former u~fl~at~ tuner, AMA tech inspector; Technical .;Clø V'~'1d; part-time rocket scientist Yamaha two-strokes

I HAVE NO FAVORITE BIKE, IN THE sense of a romantic attachment to a thing. A particular machine is just a snapshot of its builder’s thinking at one instant. It’s conceptually obsolete as soon as it’s built, because the builder’s mind moves faster than his hands. So I will name a family of machines, developed and elaborated upon over 27 years for both street and track, with which I have had a lot of experience and, yes, fun.

That series began in 1970 with the Yamaha R5 horizontally split twostroke street Twin, evolved quickly into the air-cooled TD3 and giantkilling TR3 roadracers of 1972, then into the liquid-cooled TZ350. A liquid-cooled 250 racer appeared in

1974, along with the TZ750A, which despite being an inline-Four, was based upon the same modular bore/stroke, cranks, rods, bearings and basic ignition. That 750 arrived with 90 horsepower, won Daytona nine times in a row, and was still strongly competitive in 1983 with 140 bhp.

The very popular RD250/350 populated the highways, bringing reedvalve power to that sphere, on a crankcase essentially interchangeable with that of the TZs. When those production-based TZs left the stage at the end of 1980, the 250 was closing in on 60 bhp, and the best 350s were making more than 80. But the basic design wasn’t finished yet, for the

longer-stroke RD400 carried on with virtually the same gearbox, cases and bearings, passing many of the original 1970 features to the powervalve-equipped RZ350 liquidcooled streetbike of the early/middle 1980s. It was to its time what 600cc sportbikes are to the present. That 1970 lineage continues to this moment as the Banshee ATV engine.

Having traveled thousands of miles in vans, carrying these machines to and from races, having built cranks, cut cylinders and made pipes for most or all of these critters, I almost feel like a member of the family.

CountY,

Y FAVORITE MOTORCYCLE, LIKE

my favorite sexual experience, was my first. Both were short, poorly designed and, in every way, technical debacles, which dilutes their significance not a whit.

My first motorbike was a mowerless lawnmower, a.k.a. a minibike. Mine was a 1969 Taco 22, model XSomething...I forget. It was a 62-pound, 3-horsepower Briggs & Stratton, suspensionless, 37-mph trail-smoker with a friction tire pad for brakes and a little sign taped between the handlebars by Mother that said with breathtaking futility: “BE CAREFUL!”

You see, she knew. Her boy was no longer only hers, and her challenger was a machine. The care that she wished I take was for my heart, not my flesh.

I choose to believe that we develop emotional attachments to machines when we share traumatic, hazardous experiences with them. This is why men love their fishing boats in a way women could never love their Electrolytic Home Hair Removers. Pursuing risk with a machine-normally, but not always, a male passion-cements a special relationship. Steel becomes soul. With our gizmos of peril, we male animals celebrate the shared triumph fp of a painful jourJLPCHCIF ney survivec*’ pat_ ting our machines stupidly, calling them “she” and occasionally naming them. Give a man a saber saw, let him come close to cutting off a finger and he’li soon be addressing the tool as “Pinky” or “The Dusty Digit Diddler.” The first rumblings of a special love will have stirred.

And at 12 years, I loved my Taco 22 model X-Something minibike because it carried me smack dab through the worst horrors of puberty and delivered me home safely again.

It was the summer of 1970 and I was riding my primordial motorcycle by the Encino, California, house of the adorable primordial woman Ricci Vinyard, when she happened to stroll out, smile and wave me over. It was at this precise moment, when the cosmic elements of adolescent triumph momentarily aligned (boy, dreamgirl, minibike), that the gods sent a honey bee up a nostril at 37 mph to drill its stinger behind my left eyeball.

With a deftness of mind and muscle that comes bundled only with the software of youth, I maintained my heading by steering with my thighs as my left hand-hidden from Ms. Vinyard’s view-clawed into my swelling, slobbering nose to remove the struggling beast. My right hand rose toward the beckoning blond and I waved back, as if to say no time, baby, I’ll catch you later.

And she was gone. Forever.

I don’t know what happened to Ricci Vinyard, but I know that her lasting memory of me was that of the only boy in Portola Junior High who dared pass her by, riding alone and rebel-like toward the sunset on a motorcycle. Better she know that than the truth, which is that just down the road I was on my knees with 10 fingers up my honker, weeping.

The Taco 22 was a noisy, brakeless piece of ca-ca, but we will always have Encino.

COOK t1Eh1~!~IO photo~Tap"~'; EditOl, Cycle Calil01I~~a ot~Rod Sometime last to tame tne I 970-79;

AT THE END OF JUNE, 1963, MY otherwise utterly empty head contained but three ideas: 1) That I had to have a motorcycle; 2) that “Meeting the Nicest People” was a non-starter; and 3) that time was running out.

I had just completed my freshman year in college and as I saw it, my future was inevitable. Finish with school, sign up for some kind of military service, then strap on a necktie and forage earnestly through a predictable world. If I was going to wedge a bike into my life somewhere it had to be...now.

Motorcycling’s tilting landscape 35 years ago, at least as far as streetbikes were concerned, held more variations than you can imagine. But the strictures of time concentrated my focus toward the higher altitudes, and enthroned there was the first of my two favorite motorcycles: the Harley-Davidson XLCH Sportster,

1964 version,

883cc, $1435, VTwin, perfect primary imbalance. As soon as I saw it at Tommy Hannum’s dealership in Media, Pennsylvania, I knew that this was a telegram edged in black, and that it was mine.

By the time I finally parted company with my Harley 10 years later (only a cut-down primary cover and a heavily modified Fairbanks-Morse magneto were left from the original), we had gotten ourselves thrown out of college for a year; removed from Pennsylvania’s list of citizens with valid operator’s licenses (122 in a 50), dragooned into the military; reduced in rank from sergeant to one pay grade below private for an incident involving nitromethane, tire smoke and a commander with a diminished sense of humor; and into four good-sized wrecks, only three of which were our fault.

Along the way, my CH served as a commuter vehicle, a means of visiting my girlfriend, a long-distance touring bike, a three-time Bonneville record-holder and, briefly, an NHRA op Fuel recordholder. Early on, it carried me around the legendary Grafton Scrambles

track one lovely summer’s day. I used it to sell encyclopedias door-to-door in Louisville,

Kentucky, and to get to my job in a cement factory in Tampa, Florida. Later, before I sold it, my Sportster logged a quarter-mile trap speed of over 170 mph at Orange County International Raceway’s dragstrip.

For 10 years the bike was more than a noisy adjunct-it was a defining presence in my life, and it reshuffled everything. After Bonneville in

1966 I wrote a little piece for the Harley-Davidson Enthusiast, and just before I graduated from college in

1967 I sent a story to Cycle World about Sonny Routt’s double-engined Triumph dragster that Editor Ivan Wagar actually published. By September of that year, I was on the staff of Cycle magazine in New York City and my life had swung onto an arc that I couldn’t have imagined four years earlier.

Not to say that the Sportster was a particularly brilliant motorcycle. On some cold days it would take as long as an hour to start. For as long as I used it as a streetbike, it made its way down the road with a quaint, weaving motion that applications of steering damper

merely aggravated, and it could never get very far down that road because the fuel tank only held 2 J4 gallons. It vibrated with a determination unmatched by any motorcycle that I ever rode, and when we goosed displacement from 883cc up to lOOOcc for Bonneville in 1966, the jack-hammering got even worse. The suspension wasn’t so hot either, and neither were the brakes. It burned out alternators and fried voltage regulators and defilimented headlamps.

But this is irrelevant sniveling, because the XLCH was never about “good,” it was about horsepower, and through the years my pursuit of this unholy grail led me to people like Jerry Branch, Tom Sifton, Dick O’Brien and George Smith, and to chemicals like nitromethane, benzene, methanol and the nastiest of all, propylene oxide. The chase for more and more power also caused me to become intimately familiar with engine internals, since nitro has a way of making internals...external.

(A conversation I’ll never forget: My friend Charlie Kowchak came with me to Bonneville in 1969. We were running what was called a “heavy load”-95% nitro, 5% propylene oxide. Charlie, driving the tow car, met me at the end of the track after a memorable qualifying attempt. “How’d it go?” he asked. “Fine,” I answered, “but I think I might have hurt it.” “Are you sure?” he asked.

“Just guessing,” I said, “but there’s a whole piston on top of the oil tank.”)

As you may have figured by now, my Sportster never stayed the same for long. Like a little kid with a pile of Legos, I would change its pieces and put them together all different kinds of ways: stock streetbike; loud streetbike; loud modified streetbike; loud modified streetbike/drag racer; Bonneville racebike; back to streetbike; all-out gasoline drag racer; allout nitro-burning drag racer; nitro Bonneville bike; then, and finally, a nitro drag racer again.

Through it all, my CH was an indictable co-conspirator and unsavory influence, chuffing happily or exploding enthusiastically from Unionville, Pennsylvania, to Tampa, Florida, to New York City to Alton, Illinois, to Miami Beach to Wendover, Utah, to Los Angeles. We went everywhere and did everything, and at the end of the day, even though we had put a few dings and scratches on each other, my love for that bike was undiminished.

Favorite motorcycles aren’t just about motorcycles; they’re about experiences, good and bad, the more sharply drawn and luxuriantly colored the better. With my Sportster, I had plenty of both, certainly, but beyond that the bike deflected the trajectory of my passage. Who knows? Without my Harley I might have become another goddamned lawyer.

One last thing: Back in 1963, while I was trying to figure out which was the Maximum Motorcycle, I remember the following in Cycle World's road test of the 883 Sportster: “It’ll grow hair on your chest, then part it down the middle.” That road test sold me on the XLCH. It was written by CWs then-Technical Editor Gordon Jennings. By 1966, Gordon had been lured away to New York City by Cycle. Because I wanted to work for him, that’s where I applied. Because I had a Sportster, he hired me.

Favorite motorcycles can’t do any more for you than that.

Almost forgot. Earlier, I mentioned that the Sportster was one of my two favorite bikes. The other one is a certain 750cc Ducati Desmo Super Sport, vintage circa 1974. V-Twin. It ended up with a displacement of exactly 883cc. Go figure.

IO~ SCALZIJ Book author; magazine Write,; VaIUflt~0, fir.~ f~Qhter; afraid of fJ~I~g, not of Gary BS~ "G~B~~ HOt~.t

ANYBODY GROWING UP IN L.A. in the early Sixties who spent Friday nights at Ascot Park Speedway getting off on the highjinks of the BSA Wrecking Crew, knew that those guys had their pristine, trick Gold Stars (like those of the late AÍ Gunter), and their slob Gold Stars (like Neil Keen’s).

Neil “Peachtree” Keen,

National Number 10 (the 0 painted in the shape of a donut), liked playing head games. His beau■ ties were never as raunchy as ¿ they seemed, and he was especially creative and witty about utilizing tools for an Incorrect Purpose (I.P.). Neil concocted the Green Hornet, which was a Gold Starj roadracer equipped not with clip-ons, but a giant flattrack handlebar; and its throbbing, riffing heart wasn’t standard Beezer pavement-issue, but a wild Ascot Park dirt-track cruncher with big Axtell camshafts. All in all, this was a typical Keenesque brew-fast but scary. And I forgot to add that it was clothed in a bulbous and ill-fitting streamlining off a Harley Hog that wasn’t so much hornet green as gopher-guts green. Everything was I.P. out the butt.

Getting to pull the trigger on this mechanical masterpiece in a 50-mile national for sophomore professionals on the Iowa road course of Greenwood, just outside Des Moines, was a scribbler-cum-racer: me! Another dose of I.P.

It was the summer of 1964, and 1964 was a very good year for me. Except that at Greenwood, I developed a case of pre-race heebie-jeebies that was untreatable even by popping a pair of pills (these were the spacedout Sixties) that Neil’s ex-spouse used as prescription for migraines (still more I.P.).

The big glitch was that it was raining. Straight down. And I was given to fantasizing that the Green Hornet’s motor was the actual ’lunger Neil had used to take down ÊâT Carroll “Mooch” Resweber in Ascot’s classic 8-mile national of 1961. Suppose I broke it? What could feel worse than detonating the artifact that had eaten Mooch-the-Master’s lunch?

Not to worry. Drenching rain in the electronics parked us out on Greenwood’s water-logged far end, but not before the Green Hornet had demonstrated that it had engine on a certain high-llama Matchless G50, which won.

The sun was shining the next weekend over in Illinois for the roadrace national at Meadowdale. But the jerks teching the bikes were the same fussbudgets who, upon inspecting the Green Hornet at Greenwood, had called it terrible names and threatened to flunk it. Shortly afterward, though, when I came smoking onto Meadowdale’s Monza Wall at 100plus, the Green Hornet did something that slammed shut my sphincter.

Afterward, I doubted I could will myself to ever open its throttle all the way again.

I didn’t have to. During a preliminary sprint for the 250s, a HarleyDavidson short-tracker cunningly rigged with big bars and clutch and brake lever on the same side (more I.P.), raced by The Man himself, Bart Markel, centerpunched Dan Haaby, the high-llama G50’s regular rider.

Haaby’s collarbone got wellsnapped; I was called in as his emergency replacement in the amateur national. The G50 and I suffered a heartening loss to-you guessed it-more I.P. A Milwaukee Vibrator KR with a flat-track handlebar, raced by a Bart Markel protege with an attitude named John Zwerican, did a number on us.

In any case, what a hoot to at long last pay homage to the most “alive” scooter I ever threw a leg over, that bitchin’ Green Hornet BSA.

Neil took it home to California for the winter round of dirt nationals. First, he crap-canned its brakes, streamlining and other roadracing I.P., then got a new and stone-cold triggerman called Don “The Assassin” Butler. He lived up to his nickname with a wide-open lap of the Sacramento Fairgrounds, which terminated with a connecting rod ripping loose and the old Green Hornet’s face getting blown off. Sic gloria.

PHIL SCHILLING Former roadrace tuner/sponso, Edjt~, Cycle 1979 I 988; expert in breeding habits of Wheaten Terriers

IN THE SUMMER OF ’61 I fell for the Americano. Anyone who knew my past could see the fall coming. Two years earlier, I had been smitten by Ducatis and utterly beguiled by the little roadracers from Bologna. But my affair of ’59 was just a goofy romance. At 18, photos and posters and daydreams were as close as I came to a Ducati.

At 20,1 was experienced. By then I had already spent one summer trying to make a dead Indian arise and run. Every day for 70 days this 80-cubicinch Chief proved itself a worthy occupant of the ditch from which I had rescued it. My second Indian, a verticalTwin Warrior, came straight from Quirk City. Its many foibles included a third gear that could only be divined by upshifting from second, through a false neutral, on to fourth and back down to third. My next motorcycle, a new 125cc J-Be Sachs, did have a fully operational gearbox. Alas, this two-stroke buzzer routinely flinched and seized at 48 mph, and that self-governing feature came as standard equipment straight from the showroom floor. I was not amused.

Thus, my worldly motorcycle experience, which amounted to about 2000 miles of riding, pushing and walking, left me disappointed with my choices.

In ’61,1 swore to choose wisely and follow my heart.

I wanted a 200cc Ducati Super Sport with racy clip-on bars and a sculpted “Continental” gas tank and a small, unyielding competition saddle. The Super Sport engine had a special 27mm Dell’Orto racing carburetor with an open bellmouth. If 90 mph wasn’t fast (or fanciful) enough, a “slight extra charge” would cover a competition kit for 100-mph performance.

In 1961, Ducati dealers were an exotic breed, seldom seen and rarely open. They stocked only 200cc Americanos, the “touring” model. Next to the sleek Super Sport model, the Americano was as exciting as a cardboard sandwich with a lettuce filling. How could a discriminating fellow like me accept this Turismo? The Americano had “Western cowhom bars,” deeply valanced fenders, a utilitarian 24mm carburetor, small fuel tank, an oversized chrome-plated safety bar and a hideous pinkish-red-and-white dual seat.

I certainly knew my mind. The ugly Americano was below my pretensions.

Les Smith, an exceptional dealer who also happened to sell Ducatis, coaxed me toward his Americano demonstrator. He talked me through the starting drill and turned me loose. Maybe he figured that anyone who could cope with a leftside kickstarter had the necessary survival skills for a demo ride.

Dusk was edging in from the east side of Munde, Indiana, when I rode west on the main road and then north on a county highway. Whistling past my bare head, the June air carried a heavy dampness. Out the muffler came a flat blat-blat-blat, which at low speeds was overwhelmed by the delicious whine of bevel gears turning the towershaft and overhead cam.

After a year with a crippled Sachs, the Ducati felt so athletic and longwinded. The revs rose upward forever; six, seven, seven-five, maybe eight grand. The bike’s long-leggedness could have been best explained by the Americano’s modest power and fourspeed gearbox. Such a critique would have been lost on someone who was thrilled that this Ducati could-in third gear-run at speeds unknown to the infamous J-Be Sachs.

Putting down a steady line of blats at 65 mph, that 10-cubic-inch Ducati was marvelous to me. Its speed had me gasping. As dusk slipped easily toward darkness, the Americano’s faint headlight pattern emerged on the pavement ahead. The dimly lit speedometer, with true Veglia fidelity, lied shamelessly. I was starting not to care. I was already falling for the Americano.

Despite its tacky saddle and geeky safety bar, the Americano was the essential Ducati Single. Sure, the

Americano had the dog-pizz carburetor with a Brillo-pad air cleaner; and, compared to the Super Sport, the touring 200 had a point less compression and a lowlife camshaft. Nonetheless, the Americano shared with the 200 Super Sport the same beveldrive overhead-cam engine, gearbox, frame and running gear. The similarities that united the two models were far more significant than the differences that separated them.

Out on the road, the Americano set the stage for an important realization. I had always wanted the Super Sport for its appearance and flashy trappings: the boy-racer gas tank, the competition saddle, the nifty little bars. My interest in that “racing-style” 27mm carburetor was basically visual, not technical.

Form often follows function, but more times than we care to admit, form simply follows fashion. Form and function,

I finally comprehended that evening, are two distinct things. And function defined the essential Ducati.

It was dark when I returned from my test ride. I bought the demonstrator that night. In the next three years my Americano taught me much about motorcycles. But maybe I never learned any lesson more valuable than the one I learned on my first ride: The love of function. Ö

View Full Issue

View Full Issue