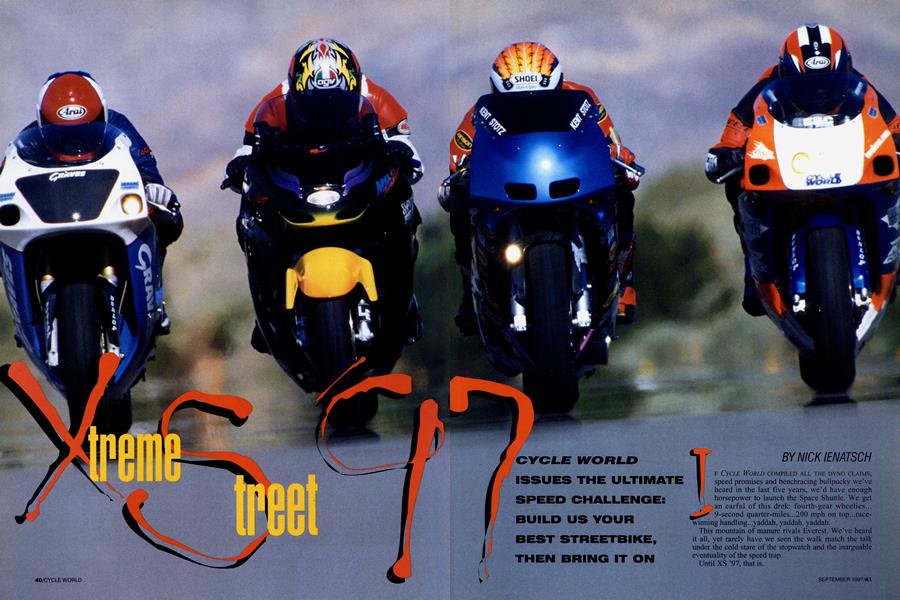

Xtreme Street 97

CYCLE WORLD ISSUES THE ULTIMATE SPEED CHALLENGE: BUILD US YOUR BEST STREETBIKE, THEN BRING IT ON

NICK IENATSCH

IF CYCLE WORLD COMPILED ALL THE DYNO CLAIMS, speed promises and benchracing bullpucky we’ve heard in the last five years, we’d have enough horsepower to launch the Space Shuttle. We get an earful of this drek: fourth-gear wheelies... 9-second quarter-miles...200 mph on top...race-winning handling...yaddah, yaddah, yaddah.

This mountain of manure rivals Everest. We’ve heard it all, yet rarely have we seen the walk match the talk under the cold stare of the stopwatch and the inarguable eventuality of the speed trap.

Until XS ’97, that is.

THE PLAYERS

The invitations our four contestants received held a few simple rules, mandating stock wheelbases but allowing swingarm extensions up to 5 inches for dragstrip duty. Onboard adjustments were okay, but major components couldn’t be replaced between the testing venues-street, dragstrip, roadrace track and top-speed run. The bikes needed to carry lights, a license plate, kickstand, mirrors and run on DOT-approved tires, and we stressed the fact that CW wanted streetbikes, not lightly disguised dragbikes that sacrificed comer-carving for simple straightline acceleration. We picked four men who had achieved success in their chosen fields of endeavor, then sat back and waited for the results. We weren’t disappointed.

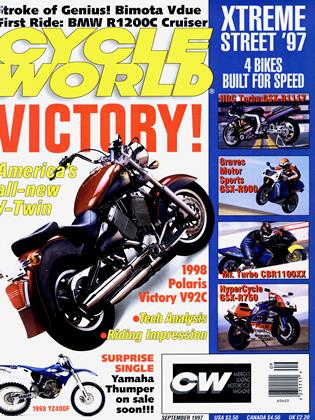

Chuck Graves, the 1993 Formula USA champion and four-time Willow Springs Formula One champion, answered the call with a Graves Motor Sports creation that shoehomed a 1996 Suzuki GSX-R750 chassis full of raceprepped RF900 engine, breaking new ground in the smallchassis/big-motor conversion world. Graves and fabricator/ machinist Mike Belcher crafted a serious weapon, and then took the time to get the bike’s details right.

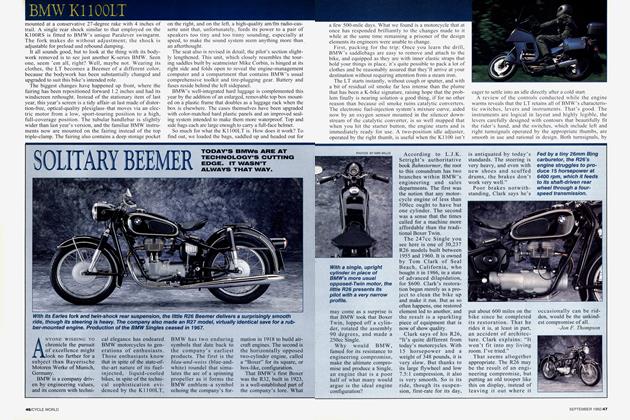

Bill Hahn Jr., the tuner behind the 1992 Prostar ProComp national drag-racing championship and a pair of Funnybike titles in ’93 and ’94, worked with Kent Stotz to build the Hahn Racecraft turbocharged, fuel-injected 1995 GSXR1117. This ultra-slick Suzuki, awash in stickers and looking every bit the racebike, comes out of Chicago, America’s hotbed of quarter-mile speed freaks, and is a veteran of Cycle World's annual Quickest Streetbike Shootout.

Carry Andrew, who rode for the 1988 and tuned for the ’95 AMA SuperTeams champions and now looks after the Suzuki GSX-R of current AMA 750cc Supersport points leader Jason Pridmore, arrived with HyperCycle’s lightly street-ized 1997 GSX-R750 racebike. Andrew rode it to the first day of testing, underlining his confidence in his lockedand-loaded, honest-to-AMA Superbike.

Terry Kizer, nine-time Funnybike and Top Fuel national champion, showed up for XS ’97 with a Mr. Turbo turbocharged, fuel-injected Honda CBRllOOXX nicknamed “XXS: Bird of Prey.” The team arrived for the first day of testing with the Honda’s paint still drying and only 50 breakin miles on the bike, owned by Pro Street Cycles’ Tom Holman. “We unloaded it on the interstate on the way from Houston and put some break-in miles on it,” Kizer said. The results were stunning in appearance and performance, though the boosted Blackbird would find itself running in direct competition with the Hahn Racecraft Suzuki, a machine as proven as the Mr. Turbo bike was new.

With that, the field was full and suddenly it was time to put all the hype and hopes to the test.

PULLING THE TRIGGER

The Pomona Fairplex, site of the NHRA Winternationals, was the venue for XS’s first day

of testing. Our four contestants paired off according to their methods of aspiration, with the turbocharged Suzuki and Honda immediately notching warm-up runs in the high 9-second range on a more-slippery-than-usual track. After a quick application of VHT traction compound, grip improved, times dropped and suddenly both bikes were dipping into the mid-9s with speeds just over 160 mph.

VICKS V&TET Backing Mr. Turbo’s XXS into the water trough prior to the burnout puts the upcoming seconds into sharp

clarity. The Honda barks surprisingly loudly for a turbobike as, front brake clamped, I spin the Dunlop in second gear to heat and clean it. I roll into the staging lights and wing the throttle to get the bike boosting. The whir of the turbocharger signals that the engine’s ready for launch and, man!, does it come out of the hole hard. I touch the horn button-activating the airshifter-for the first-to-second gearchange, then moments later thumb it again for third. My right thumb mashes the converted starter button activating the second stage on the turbo’s wastegate, immediately jacking boost pressure from 11 to 16 pounds. My left thumb punches fourth gear, and the tach slams to redline. I go for fifth. Through the lights, I know either the tire’s spin-

ning or the clutch is slipping under the pressure of 300-plus ponies. This thing’s got potential.

Terry Kizer and mechanic Mo Parsons pulled the clutch plates and added stiffer springs to the Honda because they had yet to develop a lock-up clutch. Across the paddock, no such teething problems plagued the Hahn Racecraft camp. After a handful of runs, the Pomona timing lights read 9 seconds flat at 163 mph. Good, but the Hahn guys wanted more. We recharged the air-shifter and rolled the Suzuki to the launch pad.

NICKS N&TEôs I’ve got to release the clutch more smoothly and more quickly, and that’s what occupies my mind after the

second-gear burnout. Without the added safety of a wheelie bar, a hard launch on a 300-horsepower streetbike can get ugly in a hurry, though the Hahn bike’s chassis setup really aides the all-important first 60 feet. I get it right, slamming through first gear and into second as the electronically staged boost builds, the front tire skimming Pomona’s famous asphalt. The rear Michelin spins slightly in second and I feel the rev limiter kick in just as I touch the horn button for third, the orange shift-light glowing. The bike bears down and hammers through the traps, and though the run was far from perfect, it felt damn quick-certainly the quickest streetbike run I’ve ever felt. Yeeooww! Sure enough, 8.88 flashed onto the board, the quickest time CW has ever recorded for a streetbike. Hahn & Co. celebrated hard, then confidently elected to park the bike to save it for the next three days of calamity, pending a challenge from Mr. Turbo’s Honda.

Meanwhile, Graves Motor Sports and HyperCycle had locked themselves into the low 10-second range, each machine flirting with 141 mph through the lights. Neither of the short GSX-Rs could launch hard without sky-high wheelies, and the GMS bike was further hampered by a clutch-actuation arm that wasn’t long enough to provide proper feel at the lever. Each bike made more than 20 passes, with HyperCycle’s Superbike knocking at the 9s, posting a best run of 10.03 seconds with an impressive speed of 142.83 mph, barely besting the Graves’ effort of 10.13/141.97. One thing’s sure: If you want an extreme sportbike that can be hammered at the dragstrip, either of these two fill the bill. They’re tough.

The final run of the day was Mr. Turbo’s, but Hahn’s 8.88 was out of reach for the rookie Honda. The heavier clutch springs and a decent launch slashed the Honda through the quarter-mile in 9.13 seconds with a speed of 163.72 mph, .1 mph up on Hahn’s Suzuki and a strong effort for an untried combination, but not into the 8s. Advantage Hahn.

ON THE STREET

Cycle World made it extremely clear that Xtreme Street included the word street for a very good reason, and we spent the entire second day of the test on public roads, riding each of the bikes to our right-wrists’ content.

Our route took us into the canyons north of Los Angeles, a sporting environment perfect for that dream Sunday-morning ride. Here, the turbobikes, axles moved up, were contesting for third and fourth place, even if they really didn’t do too much wrong. It’s just that the two GSX-R-based machines were simply stunning, combining the laser sharpness of the updated GSX-R750 chassis with more horsepower, and in the

case of the GMS machine, a truckload more midrange.

Our testers gave the Graves 900 the nod for best streetbike, due to that monster midrange, its awesome brakes, a well-balanced chassis and a full complement of gauges that even included the stock low-level fuel light. Factor in the team’s sano bike preparation, and you have a motorcycle that’s easy to love. Very nicely done.

VICKS VSTES We editor-types seem to enjoy being critical, but I’m hard-pressed to find anything wrong with the GMS Suzuki 900. It hums beneath me, carving up this terrific canyon as if Chuck Graves made the bike just for this road.

The engine vibrates a bit at high rpm (though it’s smoother in the midrange than the HyperCycle Superbike), and that’s about it for the Complaint Dept. The chassis is so perfectly balanced at street speeds that traction feedback from both contact patches inspires un-!?&%#@-believable lean angles. The ever-ready engine doesn’t care where the tach needle Is-this bike accelerates at will. It also looks fantastic, an important facet of streetbikesmanship, and wears the kind of jewelry that enthralls motorheads-pieces like a thumb-operated rear brake (just like Mick’s!), slick-shifting CR tranny and slipper clutch. Graves incorporated all the street paraphernalia (check out the cool projector-beam halogen slipped into the left ram-air intake), but most importantly built a rid ability into this bike that few sport-specials will ever match. Those who feel project bikes compromise real-world riding pleasure need only ride this GSX-R900 to know that hard-core doesn’t necessarily mean hard-to-live-with.

As befits a thinly disguised racer, HyperCycle’s orangeand-blue streaker made its power higher on the tachometer. Plus, it wore only a tach and temp gauge, sacrificing all warning lights and even the ignition key to the lord of low weight. “There’s no key because I don’t think I’ll let it out of my sight!” Andrew defended. Understandable.

So, what about the turbos, you ask? Both teams run relatively low boost pressures in street trim, attempting to keep the rear tire hooked to the ground and the rider hooked to the handlebars. The Hahn bike’s fuel injection started hot or cold with no more hassle than a stock bike, but the older GSX-R 1100 chassis felt heavy and dated compared to the competition. The Mr. Turbo team made some smart choices in updating the stock XX chassis, but the bike lacked some fine-tuning on the low-speed fuel injection when it arrived. Kizer and crew continued to adjust the system and eventually made significant improvements.

KNEE DOWN AT HONDA HEAVEN

Exploring the outer limits of these four bikes mandates a closed course, and we know no better locale than the Honda Proving Center of California, or HPCC. The Honda test track twists and turns through the Mojave Desert, exhibiting elevation changes, slow comers and fast sweepers over its 2.5 miles. It’s a lightly disguised racetrack, really, used to test every product Honda makes, including those wrapped in Smokin’ Joe’s colors.

Both turbobikes surprised testers unaccustomed to these monsters-they felt almost comfortable running on a roadcourse. Yes, they accelerated far too hard and yes, rear-tire traction had to be monitored with an eagle’s eye, but both the Mr. Turbo and Hahn Racecraft machines encouraged a quick pace by providing plenty of cornering clearance and ample stopping ability. The Honda’s solid chassis and outstanding Brembo brakes placed it ahead of the Hahn bike, though the turbo Suzuki made more power earlier in the powerband, allowing it to “point and shoot it” with smileproducing results. Mr. Turbo had tuned the boost to come in a bit later, allowing a low-boost corner exit that made an ambulance ride that much more unlikely.

Hahn’s machine was plagued with a slight looseness at the rear, as if the tire was low (it wasn’t), and the bike’s best time was six-tenths of a second off Mr. Turbo’s quickest lap, a 1:52 flat. Had the Hahn bike challenged, our testers felt certain the Honda could be pushed to go quicker, but even with Miguel Duhamel aboard, it wasn’t about to catch the HyperCycle or Graves Motor Sports efforts. These built GSX-Rs know a thing or three about getting around a racetrack.

VICKS VÔTEô It usually takes a few laps to get a feel for a bike, but HyperCycle’s Glxxer immediately feels comfortable at speed, as if I’ve ridden it all my life. By the third lap, I’m beginning to wonder how far this “streetbike” can be pushed, and already I’m running entrance speeds normally reserved for slickshod race bikes.

Touch the brakes and flick it in, pick up the throttle and feel the light bike slingshot toward the corner exit, the front

and rear tires telegraphing traction information as my knee skims past the corner’s apex. This thing’s good. Another lap and another thought: This thing’s perfect.

Carry Andrew and mechanic John Ethel worked with the intensity usually reserved for an AMA national and were more than happy to make any necessary changes. A few slight adjustments to compensate for the track, and the bike clocked an ultra-quick 1:48.5-second lap, the quickest we’ve seen from any streetbike at HPCC. Andrew’s smile was earto-ear. This is what he came for-to show the world how good a streetbike can handle when the stopwatch is ticking. You will see this very machine, minus the lights, starter and charging system, under Jason Pridmore sometime this year, lined up against the best factory AMA Superbike teams.

Graves didn’t go down without a fight-a fight that brought the team to within a scant three-tenths of a second of HyperCycle’s Superbike. Graves and Belcher had to hurriedly diagnose a frustrating misfire caused by a broken coil lead, and then they worked with our testers to dial in the bike for the track. The larger GSX-R was significantly more twitchy than the HyperCycle entry, due to the aggressive steering geometry and Öhlins fork that wasn’t quite as smooth as the later-model Öhlins unit used by HyperCycle. When the day ended, Graves Motor Sports had mounted a serious challenge, but couldn’t quite match the GSX-R Superbike.

The teams went to sleep that night having survived the abuses of three days of hard-core testing, but day four would bring the toughest challenge of all: top speed.

FULL-RIP,FLAT-OUT

The group met shortly after dawn at the Altar of Big Speed, HPCC’s 7-mile oval, which consists of a pair of 2-milelong, unbanked corners connected by 1.5-mile straights. There was an edge in the air; these guys were hungry for speed. We were, too. Manning the traps were the Southern California Timing Association’s Jack Dolan and Honda’s Gary Christopher.

HPCC’s top-speed drill is simple, but difficult. You leave the pits, loaf down the first straight, pick up the pace a bit in the comer, get serious halfway through and start making hay when the corner dumps out onto the timing straight. You come off the comer at more than 155 mph and let ’er rip.

The turbos gulp down the straight in one lunging, tirespinning breath, while the normally aspirated machines must cheat aerodynamics for that last 50 rpm on the tach.

The challenge is getting off that last corner, a delicate combination of lean angle and throttle that, if done wrong, will highside you all the way to Edwards Air Force Base.

Mr. Turbo’s Terry Kizer looked over his Honda and pronounced it fit, saying, “Run it down there and see how it feels. Let’s make this a warm-up run, then check it over and go for it.” Three minutes later, the radio reported 197.368 mph, this with a slipping clutch. The team went to work, but misfortune struck on the next run. Before the traps, under boost at well over 200 mph, a piston destroyed itself on the all-new machine. “Hey,” Kizer said, “we came here for R&D, so now we know the weak link.” The potential-laden Honda was done.

Meanwhile, HyperCycle laid down a 188.284-mph first pass to outgun Graves’ 183.299-mph initial attempt. Carburetion and gearing changes didn’t help HyperCycle much, and Graves crept closer. With the pressure on, the 750 uncorked a pass just over 189 and Carry Andrew knew he had a combination that would fly. One last gearing change and he patted his baby, saying, “Let’s do it.” The bike piled down the straight and slammed through the traps at 191.082 mph, the fastest normally aspirated 750 Cycle World has had the pleasure of firing past the timing lights.

But Graves wasn’t done. The team demon-tweaked their 900, levering the brake pads back from the discs for reduced rolling resistance (don’t try this at home) and waxing the windscreen for more slippery aerodynamics. The bike hauled through the comer in sixth gear and wailed through the traps, running into redline and delivering a 190.274-mph run, leaving it an agonizing .8 mph off HyperCycle’s speed.

Awesome as it was, the GSX-R Speed War paled with what was about to come. Hahn Racecraft’s initial pass pushed our tester’s eyeballs to the back of his skull with a 218-mph shot. But more was in store. The team regeared and added a bit of boost: 225.565 mph. A 45-minute cooldown period and a few more pounds of boost later, and Hahn’s GSX-R 1117 turbo launched off the comer and tore through the timing lights at 230.179 mph, only .5 mph off the fastest streetbike (or any bike, for that matter) ever tested at HPCC. The Hahn crew could taste it. But the next run ended halfway down the timing straight when the bike quit making boost. Back in the pits, the Hahn crew looked sick-until they discovered a loose hose clamp on the boost tube, the culprit for the loss of power. That repaired, the real mn began. And it would be good.

VICK.6VÖTEÖ,

We’re coming off the corner with at least 170 mph in hand, and it’s simply a matter of pointing down the long straight and through the traps, resisting the urge to cut the throttle as the chassis squirms with the kind of accelerative forces Suzuki engi-

engineers never dreamed of. The bike wiggles and floats, but there’s no safe, painless way of aborting the run, so you learn to move your weight around the bike, searching smoothly but quickly for the combination that works, all the while watching the tach and searching for the timing lights. I weight the pegs and the bike mellows a bit, charging forward with a 20-second onslaught of massive, overwhelming speed. We are on the way to a speed few bikes have ever seen, even at Bonneville, and certainly no streetbike has ever attained. The orange shift light glows in top gear just as we enter the traps. Perfect!

The Hahn bike rolls to a stop in the pits and its rider nods, giving the thumbs-up. “That was a good one,” is all he’ll say. Ninety seconds later, Gary Christopher calls it in: “Are you all gathered around the radio?” We were. “The Hahn Racecraft machine just recorded a run of 233.766 mph. Congratulations to the crew, they’ve just set an all-time HPCC speed record!” The pits erupt.

SPEED BOYS

Given the credentials of the players involved in Xtreme Street ’97, the synapse-snapping performance of these four bikes might have been expected. What really surprised us, however, was the amount of time and energy poured into each XS motorcycle. Rather than warmedover stockers with a nitrous bottle strapped on, these four speed specials were engineered to represent each tuner’s view of the ultimate sportbike. We glimpsed the true meaning of the term “racebikes-with-lights” thanks to the expertise of Graves Motor Sports and HyperCycle. And we experienced the mind-spinning miracle of fuel-injected, turbocharged street missiles through the magic of Hahn Racecraft and Mr. Turbo.

For those tired of committee-think riding positions, innocuous color choices, board-mandated horsepower outputs and handling attributes aimed at everyman, an XS bike is a breath of fresh, rare air. The edges are sharper, the limits higher, the thrills larger and the rewards greater. XS ’97 focused on four machines taken to extremes by championship tuners who lunged at the chance to build the type of streetbike enthusiasts have dreamed about. After years of hearing all about speed, acceleration, handling and ultra-trickness, we found four men who let their bikes do the talking.

And the listening was good. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

September 1997 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

September 1997 By Peter Egan -

Columns

ColumnsTdc

September 1997 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1997 -

Roundup

RoundupAt Last! Bimota's Two-Stroke Hits the Street

September 1997 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupSpied! New Yamaha Superbike

September 1997