Ode to Old Blue

Once more, with feeling

COOK NEILSON

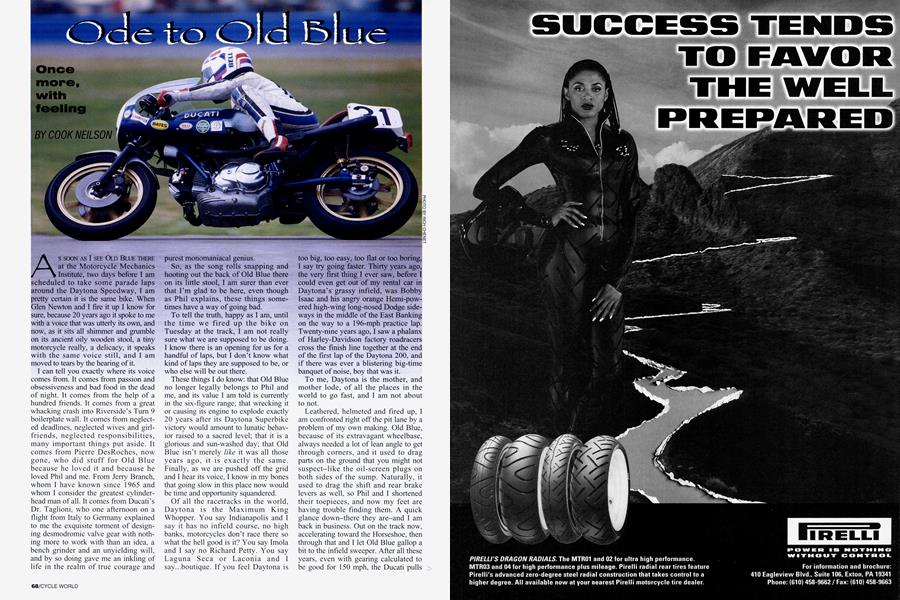

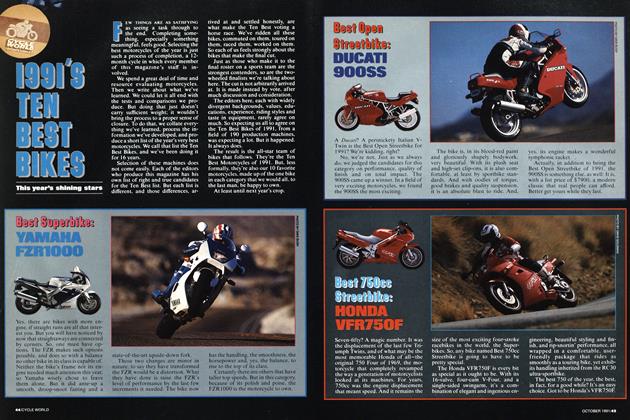

AS SOON AS I SEE OLD BLUE THERE at the Motorcycle Mechanics Institute, two days before I am scheduled to take some parade laps around the Daytona Speedway, I am pretty certain it is the same bike. When Glen Newton and I fire it up I know for sure, because 20 years ago it spoke to me with a voice that was utterly its own, and now, as it sits all shimmer and grumble on its ancient oily wooden stool, a tiny motorcycle really, a delicacy, it speaks with the same voice still, and I am moved to tears by the hearing of it.

I can tell you exactly where its voice comes from. It comes from passion and obsessiveness and bad food in the dead of night. It comes from the help of a hundred friends. It comes from a great whacking crash into Riverside’s Turn 9 boilerplate wall. It comes from neglected deadlines, neglected wives and girlfriends, neglected responsibilities, many important things put aside. It comes from Pierre DesRoches, now gone, who did stuff for Old Blue because he loved it and because he loved Phil and me. From Jerry Branch, whom I have known since 1965 and whom I consider the greatest cylinderhead man of all. It comes from Ducati’s Dr. Taglioni, who one afternoon on a flight from Italy to Germany explained to me the exquisite torment of designing desmodromic valve gear with nothing more to work with than an idea, a bench grinder and an unyielding will, and by so doing gave me an inkling of life in the realm of true courage and purest monomaniacal genius.

So, as the song rolls snapping and hooting out the back of Old Blue there on its little stool, I am surer than ever that I’m glad to be here, even though as Phil explains, these things sometimes have a way of going bad.

To tell the truth, happy as I am, until the time we fired up the bike on Tuesday at the track, I am not really sure what we are supposed to be doing. I know there is an opening for us for a handful of laps, but I don’t know what kind of laps they are supposed to be, or who else will be out there.

These things I do know: that Old Blue no longer legally belongs to Phil and me, and its value I am told is currently in the six-figure range; that wrecking it or causing its engine to explode exactly 20 years after its Daytona Superbike victory would amount to lunatic behavior raised to a sacred level; that it is a glorious and sun-washed day; that Old Blue isn’t merely like it was all those years ago, it is exactly the same. Finally, as we are pushed off the grid and I hear its voice, I know in my bones that going slow in this place now would be time and opportunity squandered.

Of all the racetracks in the world, Daytona is the Maximum King Whopper. You say Indianapolis and I say it has no infield course, no high banks, motorcycles don’t race there so what the hell good is it? You say Imola and I say no Richard Petty. You say Laguna Seca or Laconia and I say...boutique. If you feel Daytona is too big, too easy, too flat or too boring,

I say try going faster. Thirty years ago, the very first thing I ever saw, before I could even get out of my rental car in Daytona’s grassy infield, was Bobby Isaac and his angry orange Hemi-powered high-wing long-nosed Dodge sideways in the middle of the East Banking on the way to a 196-mph practice lap. Twenty-nine years ago, I saw a phalanx of Harley-Davidson factory roadracers cross the finish line together at the end of the first lap of the Daytona 200, and if there was ever a blistering big-time banquet of noise, boy that was it.

To me, Daytona is the mother, and mother lode, of all the places in the world to go fast, and I am not about to not.

Leathered, helmeted and fired up, I am confronted right off the pit lane by a problem of my own making. Old Blue, because of its extravagant wheelbase, always needed a lot of lean angle to get through corners, and it used to drag parts on the ground that you might not suspect-like the oil-screen plugs on both sides of the sump. Naturally, it used to drag the shift and rear brake levers as well, so Phil and I shortened their toepieces, and now my feet are having trouble finding them. A quick glance down-there they are-and I am back in business. Out on the track now, accelerating toward the Horseshoe, then through that and I let Old Blue gallop a bit to the infield sweeper. After all these years, even with gearing calculated to be good for 150 mph, the Ducati pulls with such resolve that I can’t help giggling-two decades gone by and its engine hasn’t forgotten how to behave. Neither has its chassis or suspension.

I must confess here that with regard to the complicated business of making a motorcycle handle properly at speed, Phil and I got off easy. I look at modern Superbikes and I see adjustments, sensors and telemetry in the neighborhood of suspension components, and I read how critically important it is to get these bits right. Since weight and power are the enemies of handling and Old Blue had little of one and just the right amount of the other, here’s how it was for us. Step One: Space the front wheel so the fork doesn’t bind. Step Two: Apply hydraulic fluid to the interiors of the two fork pipes in roughly similar quantities, and install a Chevy valve spring atop each fork spring. Step Three: Grease the swingarm bushings and rotate the rear spring adjusters for maximum preload. Execute these steps once per season. Go racing.

See, our Ducati never had anything that felt like a handling problem. It only had handling characteristics, and these resulted from its wheelbase length and steering-head inclination. Once we fitted extra-long rear shocks (to reduce rake) and stiffer fork springs (to keep it from dragging too many parts on the ground), we were home free. Old Blue would push its front end a smidge in high-speed turns, but it did it so predictably and with so much feedback that you had to be a moron not to notice.

I notch it back a gear and the bike whistles through the sweeper without a wiggle or a bounce. I throw out the hooks for the next nasty little U-turn right, and all of a sudden we are in the middle of the final infield corner-and confronting an array of orange cones, put there to force traffic toward a wider and safer line. In the good old days, I liked to stay in closer than these cones allow. My “Gary Nixon” line here allowed me to accelerate earlier and vault up on the West Banking with a full head of steam, and even though there was a pavement angle change-you could call it a ditch-in exactly the wrong place, Old Blue never noticed. At that one spot on the track, an early apex and a big drive disguised the Ducati’s only shortcoming: low-gear acceleration.

Past the cones now, up on the banking, and I chase the bike toward what feels like redline (I am guessing here, because it turns out the only component that has diminished over the passage of time is the tachometer). Old Blue never misses a beat, and I am free to enjoy Daytona’s most captivating sensation: that of the track looping over my head as centrifugal force presses my chest onto the fuel tank. I have always loved this, even back in 1968 on my illegitimate-child-ofSatan, oil-line-popping, no-horsepower-making, throwing-itself-on-theground-for-no-apparent-reason Harley 250 Sprint. Once I learned to look forward and up instead of just forward, I always found Daytona’s high banking a familiar and welcoming place to be, and I find it to be so now.

It is on the back straightaway that I am irredeemably seduced into giving Old Blue its head. The bike is so healthy and so at one with itself that I have no real choice in the matter, especially considering that the two of us probably will not come this way again.

It is here, too, that I think of Phil, who I know is pacing near the pit wall waiting for something awful to happen.

One of Phil’s fondest memories is the sound of Old Blue ripping up the front straight at Ontario Motor Speedway during a national in the fall of 1975. The bike was only a 750 then. We had gotten off to a good start from the second row that day, and at the end of the first lap all the fast guys on their lOOOcc Fours were behind us. Across the finish line the tachometer was reading just under 10,000 rpm, not that big a deal nowadays, but a startling number for a V-Twin 22 years ago.

Anyway, we got beat by Reggie Pridmore and Yvon Duhamel and some other guys, but the sound of the Ducati on that opening lap, bouncing off the trackside retaining wall and the mostly empty grandstand seats, was something that Phil never could get out of his head.

I plan in about 15 seconds to put another sound in there, to keep that old one company.

Daytona’s back-straight Chicane: It’s different than I remember, with a longer center section, but I’m not in a big rush here so we just ease on through and scamper back to the familiar arch of the East Banking, shifting into fifth just before the tunnel, the engine raucous and happy and pulling every bit as hard as it did when it really mattered. Through the tri-oval at 150 or thereabouts and I’m thinking, Phil, this is for you, and Glen, who has never heard Old Blue at its best, this is for you, too.

A couple more brisk laps, one more strafing run through the tri-oval, and we are finished, home and safe.

I find myself overwhelmed by many things: by the soul-filling joy of being aboard my favorite motorcycle on my favorite track on a shatteringly lovely day, in the company of the best people I have ever known (especially my wife, who is seeing Daytona for the first time); by gratitude for all the friends, some now gone, who helped make our bike as special as it had to be, and who patiently stayed with us until I learned how to ride it; finally, for the opportunity to go back in time and, for the briefest instant, lift the fog of decades and discover that our motorcycle really was-is-as honorable and complete as I always remembered it to be.

If I never again get to take Old Blue for a romp, and never again get to hear its voice and feel its heart, well, okay. I was lucky to have this one last chance, and this one...will do. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

September 1997 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

September 1997 By Peter Egan -

Columns

ColumnsTdc

September 1997 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1997 -

Roundup

RoundupAt Last! Bimota's Two-Stroke Hits the Street

September 1997 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupSpied! New Yamaha Superbike

September 1997