One-Man Museum

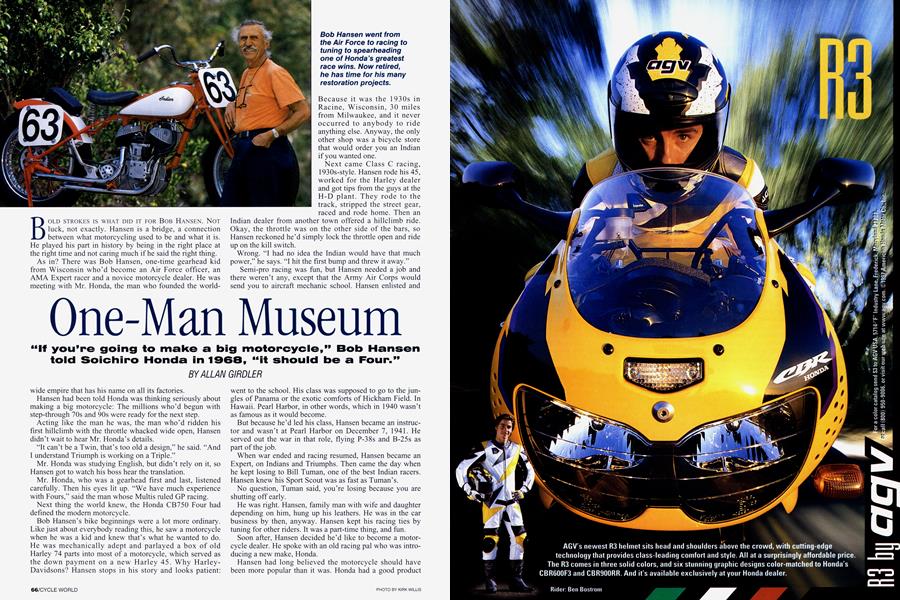

“If you’re going to make a big motorcycle,” Bob Hansen told Soichiro Honda in 1968, “it should be a Four.”

ALLAN GIRDLER

BOLD STROKES IS WHAT DID IT FOR BOB HANSEN. NOT luck, not exactly. Hansen is a bridge, a connection between what motorcycling used to be and what it is. He played his part in history by being in the right place at the right time and not caring much if he said the right thing.

As in? There was Bob Hansen, one-time gearhead kid from Wisconsin who’d become an Air Force officer, an AMA Expert racer and a novice motorcycle dealer. He was meeting with Mr. Honda, the man who founded the worldwide empire that has his name on all its factories.

Hansen had been told Honda was thinking seriously about making a big motorcycle: The millions who’d begun with step-through 70s and 90s were ready for the next step.

Acting like the man he was, the man who’d ridden his first hillclimb with the throttle whacked wide open, Hansen didn’t wait to hear Mr. Honda’s details.

“It can’t be a Twin, that’s too old a design,” he said. “And I understand Triumph is working on a Triple.”

Mr. Honda was studying English, but didn’t rely on it, so Hansen got to watch his boss hear the translation.

Mr. Honda, who was a gearhead first and last, listened carefully. Then his eyes lit up. “We have much experience with Fours,” said the man whose Multis ruled GP racing.

Next thing the world knew, the Honda CB750 Four had defined the modem motorcycle.

Bob Hansen’s bike beginnings were a lot more ordinary. Like just about everybody reading this, he saw a motorcycle when he was a kid and knew that’s what he wanted to do. He was mechanically adept and parlayed a box of old Harley 74 parts into most of a motorcycle, which served as the down payment on a new Harley 45. Why HarleyDavidsons? Hansen stops in his story and looks patient: Because it was the 1930s in Racine, Wisconsin, 30 miles from Milwaukee, and it never occurred to anybody to ride anything else. Anyway, the only other shop was a bicycle store that would order you an Indian if you wanted one.

Next came Class C racing, 1930s-style. Hansen rode his 45, worked for the Harley dealer and got tips from the guys at the H-D plant. They rode to the track, stripped the street gear, raced and rode home. Then an Indian dealer from another town offered a hillclimb ride. Okay, the throttle was on the other side of the bars, so Hansen reckoned he’d simply lock the throttle open and ride up on the kill switch.

Wrong. “I had no idea the Indian would have that much power,” he says. “I hit the first bump and threw it away.” Semi-pro racing was fun, but Hansen needed a job and there weren’t any, except that the Army Air Corps would send you to aircraft mechanic school. Hansen enlisted and went to the school. His class was supposed to go to the jungles of Panama or the exotic comforts of Hickham Field. In Hawaii. Pearl Harbor, in other words, which in 1940 wasn’t as famous as it would become.

But because he’d led his class, Hansen became an instructor and wasn’t at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. He served out the war in that role, flying P-38s and B-25s as part of the job.

When war ended and racing resumed, Hansen became an Expert, on Indians and Triumphs. Then came the day when he kept losing to Bill Turnan, one of the best Indian racers. Hansen knew his Sport Scout was as fast as Turnan’s.

No question, Turnan said, you’re losing because you are shutting off early.

He was right. Hansen, family man with wife and daughter depending on him, hung up his leathers. He was in the car business by then, anyway. Hansen kept his racing ties by tuning for other riders. It was a part-time thing, and fun.

Soon after, Hansen decided he’d like to become a motorcycle dealer. He spoke with an old racing pal who was introducing a new make, Honda.

Hansen had long believed the motorcycle should have been more popular than it was. Honda had a good product and was willing to learn as well as invest. Hansen signed up. Then he suggested a Midwestern parts depot and next thing he knew, he was recruiting and training and setting up dealerships for Honda.

That gets us to where we came in, with the arrival of the CB750 late in 1969. The Four was literally astonishing. Nobody had expected it, never mind expecting how many tens of thousands of buyers would sign up.

Honda next wondered, should the 750 go to Daytona, which at the time was open to production-based 750s-a form of Class C not a lot unlike that of Hansen’s early racing experience?

Yes, Hansen said, and four factory bikes were duly shipped, backed up by 10 kits, all the parts needed to transform the roadbike into a racer, 1970-style.

Except it wasn’t quite that easy. Honda’s international racing effort had been shut down, mostly because they’d won all there was to win, so the Daytona project was given to the head of Honda’s car-racing department. He didn’t know much about motorcycle racing, Hansen recalls, but he did know about Mike Hailwood, who’d switched from bikes to cars. Perhaps thinking Americans were still behind the times in roadracing, the Honda car guy hired three Brit racers who’d never even seen the speedway.

Hansen got one pick. Again, it wasn’t exactly luck that former AMA Champion Dick Mann was, as we say, at liberty, his former employers having lost faith. Would he like to ride a Honda, Hansen asked. Yes, Mann replied.

Nor was that the toughest part. It happened that a man who knew engines was trackside when Mann set fourth-best time in practice. The spectator told Hansen that Mann’s clutch sounded as if it was slipping. They drained the oil and found it contained rubberized bits-the debris from a cam-chain tensioner not designed for the revs the race-prepped engine delivered.

Mann’s engine was re-blueprinted. While the three other team bikes dropped out one by one, Mann’s tensioner held up until 13 laps from the end, when the slack retarded the valve timing and cost him 1 second per lap. Luckily, he had a 19-second lead at the time and won handily, giving the CB750 as convincing an introduction as any motorcycle ever had.

And then, in keeping with corporate policy, Honda quit, winners again. Before and during his stint as a Honda exec, though, Hansen had operated a private team, running Matchless G50s. Odd though it sounds, Honda didn’t mind their man racing other makes. But when he built a racing Honda 250, and won, he was asked to retire the bike because customers wanted to buy one, and Honda wasn’t making any.

One door shuts, another opens, as the philosophers say. Kawasaki hadn’t been getting their competition budget’s worth and asked Hansen to run the squad, though not quite as a factory team. He and Roxy Rockwood, who’d been the AMA’s racing announcer since the Davidson brothers gave their friend Harley first place on the factory wall, coined the term Team Hansen, the first time far as Hansen can learn that the Team came before the Name.

Years before this, back in the Indian Scout days, Hansen had created a paint scheme based mostly on having a friend who worked for a maker of agricultural machinery that used a bright orange paint, keeping up with the green tractors and yellow bulldozers. This guy got the paint that wasn’t quite up to par and, always aware that Speed Costs Money, Hansen adopted the orange, with white, for his bikes.

Team Hansen was a success. AMA Champions Gene Romero and Gary Nixon, and other guys who should have been Number One (Yvon Duhamel, for example) rode the orange and white, and won. This was in the early 1970s, when the original Class C concept, the road-going motorcycle stripped for racing, had been stretched to the snapping point. But Kawasaki’s two-stroke Triples were right in there, good as the Yamaha Fours, the Triumph and BSA Triples, and clearly outdoing the Harley Twins.

But it happened again. Kawasaki wanted to take the racing team back in-house, Mean & Green instead of Outside & Orange. They wanted Hansen to run it, but when they said that his duties would also include motocross, it seemed like too much. Hansen instead went into the real-estate business.

Which earned him honest dollars, but was about as interesting as it sounds.

Still, Hansen always had motorcycles in the basement or the barn and without actually meaning to, he picked up retired G50s, old Triumphs, a couple of early XR-750s, Yamaha and Honda Singles, etc.

Today, Hansen, 77 years old, has motorcycles in the garage and in the bam and then there’s another property up the hill and that’s full of motorcycles, too.

The gearhead kid was a trained aircraft mechanic before his racing and executive days, and he’s got a well-equipped if small machine shop in the bam, which is where and how he restored a Sport Scout to duplicate the Indian he raced as an AMA Expert.

And, he says happily with a wave at the piles of wheels and tires and crankcases and derelict motorcycles covered with tarps, there are enough baskets here to be sure he’ll never run out of projects.

It’s been a rich, full circle. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMade In Minnesota

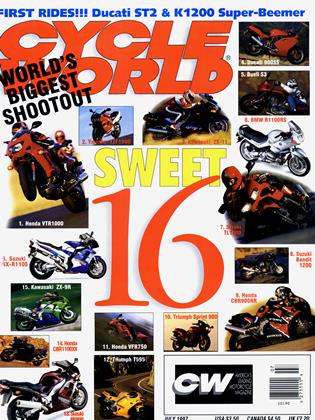

July 1997 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsSwords of Damocles

July 1997 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCOut of the Weeds

July 1997 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1997 -

Roundup

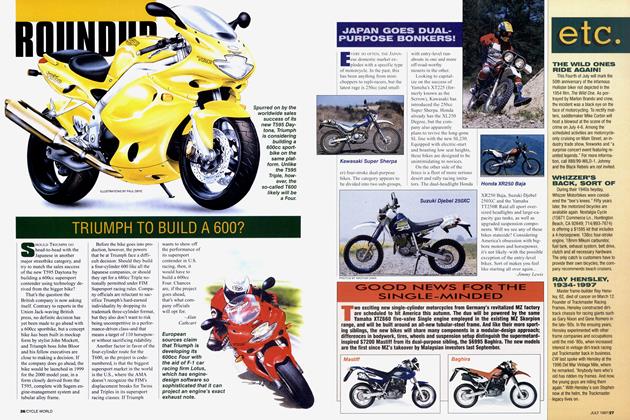

RoundupTriumph To Build A 600?

July 1997 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

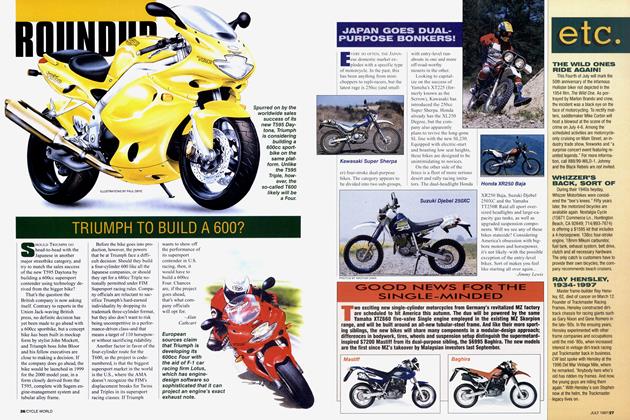

RoundupJapan Goes Dual-Purpose Bonkers!

July 1997 By Jimmy Lewis