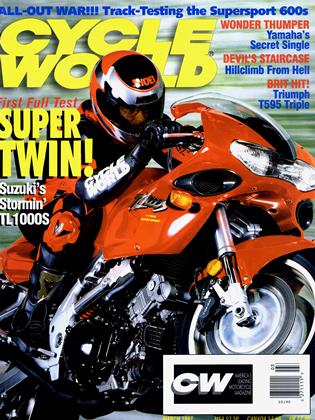

CYCLE WORLD TEST

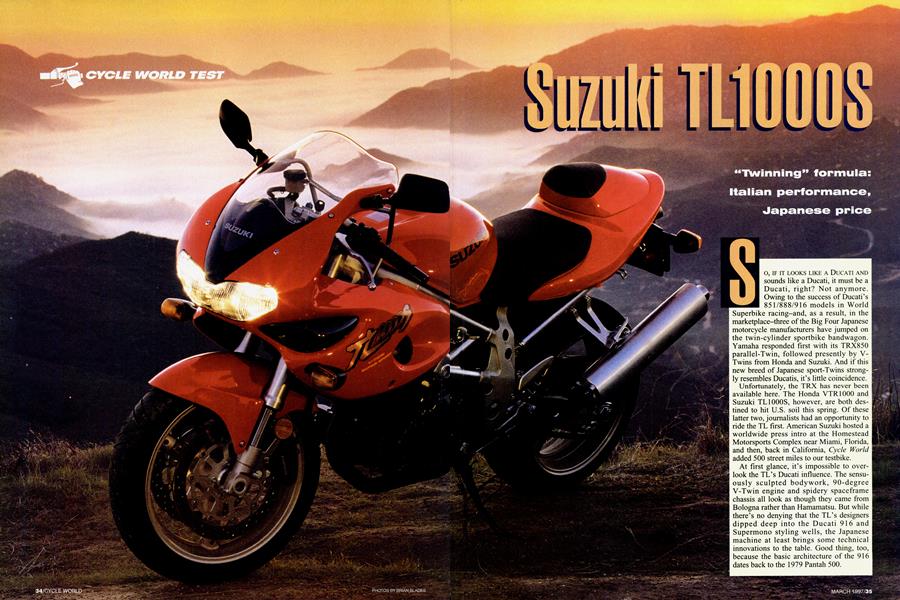

Suzuki TL1000S

"Twinning" formula: Italian performance, Japanese price

SO, IF IT LOOKS LIKE A DUCATI AND sounds like a Ducati, it must be a Ducati, right? Not anymore. Owing to the success of Ducati’s 851/888/916 models in World Superbike racing-and, as a result, in the marketplace-three of the Big Four Japanese motorcycle manufacturers have jumped on the twin-cylinder sportbike bandwagon. Yamaha responded first with its TRX850 parallel-Twin, followed presently by V-Twins from Honda and Suzuki. And if this new breed of Japanese sport-Twins strongly resembles Ducatis, it’s little coincidence.

Unfortunately, the TRX has never been available here. The Honda VTR1000 and Suzuki TL1000S, however, are both destined to hit U.S. soil this spring. Of these latter two, journalists had an opportunity to ride the TL first. American Suzuki hosted a worldwide press intro at the Homestead Motorsports Complex near Miami, Florida, and then, back in California, Cycle World added 500 street miles to our testbike.

At first glance, it’s impossible to overlook the TL’s Ducati influence. The sensuously sculpted bodywork, 90-degree V-Twin engine and spidery spaceframe chassis all look as though they came from Bologna rather than Hamamatsu. But while there’s no denying that the TL’s designers dipped deep into the Ducati 916 and Supermono styling wells, the Japanese machine at least brings some technical innovations to the table. Good thing, too, because the basic architecture of the 916 dates back to the 1979 Pantah 500.

Ninety-degree V-Twins such as those popularized by Ducati have perfect primary balance, but when placed transversely in a motorcycle’s frame, they’re too long from front to back, resulting in an exaggerated wheelbase. Ducati (and now Honda, with its VTR1000 Super Hawk) circumvented this dilemma by pivoting a very short swingarm in the engine cases, but Suzuki took a fresh approach and opted to downsize the TL’s engine and maintain optimum swingarm length. The solution is a clever hybrid chain/gear cam-drive arrangement that reduces the height of the cylinder heads. And this, in conjunction with tilting the forward cylinder back 30 degrees from horizontal, allows the engine to be positioned closer to the front tire with no worries about the two making contact. Another benefit of this setup is that you don’t have to disturb the camchains to adjust the valves; you simply lift out the cams to access the inverted buckets and the underlying shims.

Suzuki’s engineers didn’t stop there-they also adopted some space-saving measures at the rear of the engine. First, they made the engine cases shorter by staggering the transmission shafts, with the input shaft positioned slightly lower than the crankshaft axis and the output shaft slightly higher. Then, in order to fit the rear cylinder’s header pipe and the rear shock in the limited space between the transmission and the rear wheel, they decided to forgo the traditional coil-over piston-type damper setup in favor of an alternative arrangement. This consists of a tidy rotary-style damper (similar to a desert racer’s steering damper) located above the swingarm pivot that works in conjunction with a downsized coil spring that resides in a separate location behind the bottom-most, right-side frame spar. Even more interesting, the damper and the spring work through their own linkages, with different rates for each, calibrated to give the best response over all road and riding conditions. The exhaust header is then free to pass over the damper and through what would normally be the shock tunnel in the aluminum swingarm.

The result of these downsizing measures is a bike with a wheelbase of just 55.7 inches-identical to that of a 916 and only .2-inch longer than a GSX-R750. The TL is also in the ballpark in terms of weight, tipping the scales at 442 pounds dry, compared to 438 pounds for the 916 and 422 for the GSX-R750.

Like the 916, the TL is fuel-injected (it’s the first Suzuki to be so equipped since the 1983 XN85 Turbo), using a pair of single-injector, 52mm throttle bodies. These are fed by a two-stage ram-air system that varies airbox intake area to match rpm via an electronically controlled flapper valve.

Suzuki’s engineers also came up with some clever methods of coping with the high internal pressures created by the two big 98mm pistons rising and falling through their 66mm strokes. An automatic compression release eases starting, while a reed-valve-style crankcase breather vents bottom-end pressure and a back-torque limiter eases downshifts by reducing pressure on the clutch plates under deceleration; conversely, this increases pressure under acceleration, permitting a smaller clutch. As we said, the TL is chock-full of technical innovations.

The big question, though, is how do all these high-tech parts work together? The answer is splendidly. For a first effort, the TL1000 is astonishingly glitch-free. Pull on the handlebar-mounted “choke” (technically, a cold-starting enrichener) lever, thumb the electric-starter button and the big Twin fires right up, settling into a lumpy idle. The engine’s offbeat cadence is unmistakably that of a 90degree V-Twin, but the muted exhaust note is a bit disappointing; it sounds more like a pair of DR650 dual-purpose bikes idling side by side than a raucous Ducati. That, however, is our only real complaint. The TL is that good.

Snick the transmission into first gear, give the throttle a little twist, let out the clutch and the big Twin responds immediately. Like a 916, the TL is geared tall, so it takes a little clutch slippage to pull away from a stop. After that, though, there’s power everywhere, from just above idle to the 10,500-rpm redline. On the CW dyno, the TL pumped out 111.5 horsepower and 71.7 foot-pounds of torque. Then, it romped through the quarter-mile in 10.64 seconds at 132.37 mph, and posted a top speed of 159 mph. Compare this to the 916’s 104.3 bhp/64.0 ft.-lbs. dyno reading, 10.72second/ 130.62-mph dragstrip pass and 159-mph top speed, and it’s clear that Ducatisti had better watch their mirrors.

Throttle response from the fuel-injection system is crisp yet not overly sensitive; unlike some fuel-injected Ducatis we’ve ridden, the Suzuki isn’t adverse to steady-state cruising. It does, however, prefer to be revved; lugging the engine produces the same sort of unpleasant “chugging” noises that a big Single makes when you ride it two gears too tall.

The TL’s six-speed transmission feels a bit notchy during slow going, but improves at higher engine speeds, clicking through the gears with a light yet positive feel. The clutch’s back-torque limiter works wonderfully, allowing downshifts from any rpm without fear of chattering the rear wheel. By the end of our track day at Homestead we were downshifting like a two-stroke GP racer, going from fifth to second without letting the clutch out in between, and the rear tire barely chirped. Try that on a 916.

While the TL’s aluminum spaceframe and rotary rear shock are very different from a GSX-R750’s conventional twin-spar frame and coil-over damper, the two feel quite similar. The TL flicks into corners with comparable ease, holds its line and doesn’t try to stand up if you trail brake to the apex. Even better, there’s little trace of the GSX-R’s unnerving headshake. The TL’s standard race-compound Metzeier MEZl radiais stick like glue, and didn’t turn greasy at Homestead until they’d had more than 90 minutes of hard laps on them. Even then, they slid predictably, helped in part by the TL’s tractable, user-friendly power delivery; in fact, the 190mm-wide rear tire breaks loose so subtly that sometimes the only indication you’re sliding is that the bars are slightly cocked.

The Tokico four-piston front brakes work as well as you’d expect, the 43mm inverted Kayaba fork is above reproach, and the rotary rear shock... well, if you didn’t know it was unusual, you’d never guess it, because it feels like an ordinary damper. Both the front and rear suspenders are fully adjustable, handle small and large bumps equally well, and never fade.

The TL’s riding position also feels quite similar to the GSX-R’s, even if the thinly padded seat seems a little higher and the footpegs a little lower-though not low enough to hinder cornering clearance. The half-fairing does a good job of keeping wind off your chest, and the windscreen doesn’t buffet your helmet too badly, or obscure the instruments the way the GSX-R’s does. And like the GSX-R, there’s a sporty solo seat cowl that interchanges with a passenger pillion. Good stuff all around.

So, the TL1000 works very well. But is it a threat to Ducati? Absolutely. With the $8999 Suzuki offering 916 performance at a 900SS price, only dedicated Italophiles will opt to spend the extra money for the “real thing” or settle for reduced performance at a comparable price. But we suspect that many buyers won’t be choosing between a Ducati and a Suzuki, or even between Honda’s identically priced VTR1000 and the TL 1000-they’ll be choosing between a GSX-R and a TL. Tough decision. □

SUZUKI TL1000S

$8999

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Hopwood Chronicles

March 1997 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsHow Many Bikes Do You Really Need?

March 1997 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCPractical Men

March 1997 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1997 -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha Shows Wonder Thumper!

March 1997 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupTraction Calling

March 1997 By Don Canet