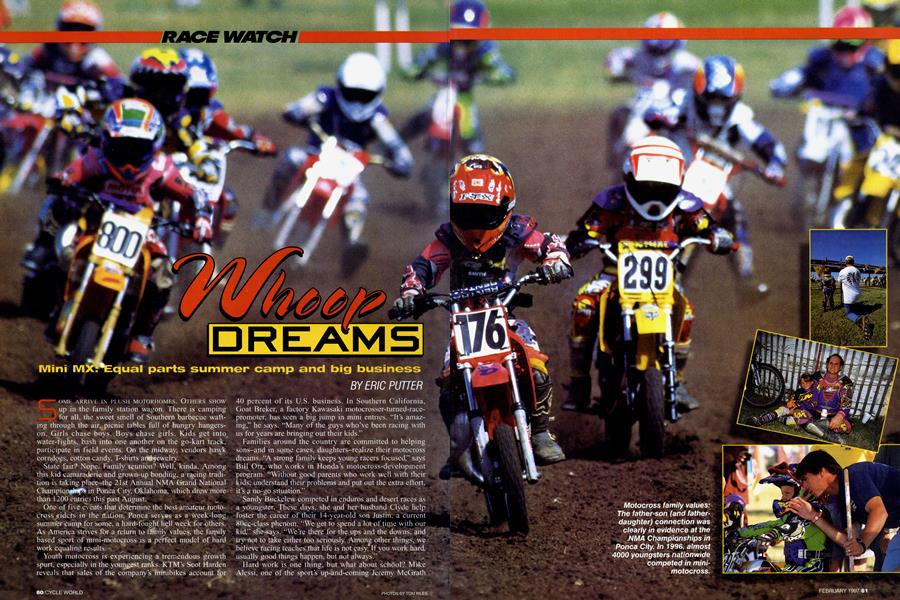

Whoop DREAMS

RACE WATCH

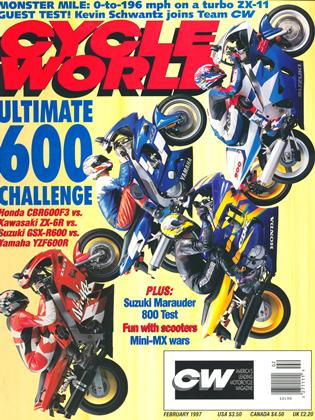

Mini MX: Equal parts summer camp and big business

ERIC PUTTER

SOME AREUVE IN PLUSH MOTORHOMES. OTHERS ShOW up in the family station wagon. There is camping for all, the sweet smell of Southern barbecue wafting through the air, picnic tables full of hungry hangerson. Girls chase boys. Boys chase girls. Kids get into water-fights, bash into one another on the go-kart track, participate in field events. On the midway, vendors hawk corndogs, cotton candy, T-shirts and jewelry.

State fair? Nope. Family ieunion? Well, kinda. Among this kid camaraderie and grown-up bonding, a racing tradi tion is taking place-thc 21st Annual NMA Grand National Champioi~ in Ponca City, Oklahoma, which drew more than 1200 entries this past August.

One of five e~fents that determine the best amateur moto crossjriders in the tiation, Ponca serves as a week-long summer camp for sonic, a hard-fought hell week for others. As America strives for a return to f~nily values, the family based sport of mini-motocross is a perfect model of hard work equaling rcsult~

Youth motocross is experiencing a tremendous g~rowth spurt. especially in the youngest ranks. KTM's Scot Harden reveals that sales of the company's ñiinibikes account f~r 40 percent of its U.S. business. In Southern California, Goat Breker, a factory Kawasaki motocrosser-turned-.race promoter, has seen a big jump in mini entries. "It~s amaz ing," he says. N'1any of the guys who've been racing with us for years are bringing out their kids."

Families around the country are committed to helping sons-and in some cases, daughters-realize their motocross dreams. `~A strong family keeps young racers focused." says Bill Orr, who works in Honda's motocross-development program. "Without good parents who work well with their kids, understand their problems and put out the extra effort, it's~~~ np~~o si~tu~ition." - - - -

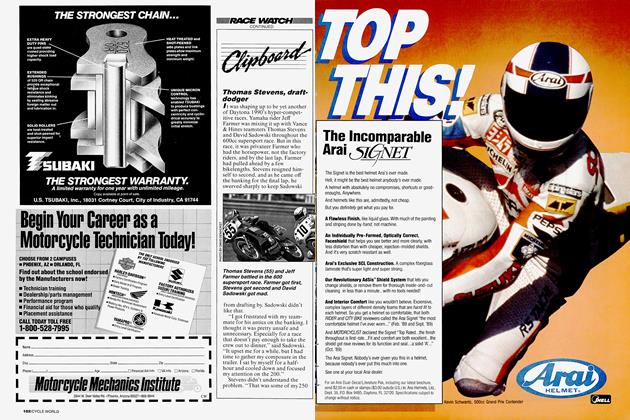

Sandy Buckelew competed in enduros and desert races as a youngster. These days, she nd her husband Clyde help foster the career of their I 4-year-old son Justin, a current 8O€~-class phenom. "We get to spend a lot of time with our kid," sfie~ays. "We're there for the ups and the downs. and trrnot to take either too seriously. Amon~ other things, we believe racing teaches that life is not easy. If you work hard. usually good things happen, but not always."

Hard work is one thing, but what about schOol? Mike Alessi, one of the sport's up~and-coming Jeremy McGrath ) wannabees, puts in the hours on and off his bikes. "Michael was named Most Improved Student last year," boasts mom Kim. "If he was failing out of school, he wouldn't be racing. He does homework first, cleans his bedroom, and then-and only then-he goes out for practice. We stress that racing is only one piece of the puzzle we call life."

Donnie Hansen, the 1982 AMA Su percross and 250cc Motocross Cham pion, has devoted his life to the sport. These days, he teaches motocross schools and takes his 8-year-old son Josh racing.

When asked if he is pointing Josh to ward a factory contract, Hansen gets defensive, then softens up: "I'm not pushing him anywhere. I give him all the support I can, but he'll only take it as far as he wants to. If he wants to work toward a factory ride, that would be great. He can do it. I'd love for him to be the next great second-generation racer (current 250cc World MX Cham pion Stefan Everts followed in his fa ther Harry's footsteps)."

In addition to learning the work ethic, some mini-MXers are earning money. Mike Alessi, one of 17 KTM mini support riders, put away more than $5000 in U.S. Savings Bonds this year for winning seven titles. In sweep ing three classes at Ponca, the 8-yearold made a quick $3000. While the bonds will mature about the same time Alessi shrugs off the effects of puberty, KTM is helping him right now: The Austrian factory gave him three bikes at the beginning of the season and an unlimited parts allowance.

And every little bit helps. "We're not rich people. My wife and I have aver age incomes," says dad Tony Alessi. "If we didn't have such great support, we wouldn't be able to do all the na tionals." Since Mike's minis are cared for by KTM technicians at the big races, Tony is free to help make back the $15,000 to $20,000 he spends get ting his family to and from the races by working as a part-time motojour nalist and racetrack announcer.

At Ponca, the younger Alessi swept three of five Pee Wee classes on KTM's Italian-made SXR5O. Kids 4 to 9 years old compete in the Pee Wee ranks. Junior Cycle is the next class, with kids ages 6 through 11 competing on Kawasaki KX6Os, almost making it a "spec" class. The 80cc classes are wide open, with riders up to 16 years old twisting the throttles on minis from the Japanese Big Four. The final division is Supermini, for 80cc-based bikes up to 105cc and riders up to 16,

To help bridge the huge gap between mini racing and the big leagues, all the major amateur races now feature 125cc and 250cc classes for youth rid ers who are either too big for their minis or too young to race in the Pros.

lo foster the sport's growth and keep bikes moving out of their respective showrooms, Kawasaki, KIM, Suzuki and Yamaha have implemented three pronged amateur support programs. Ihese consist of bonuses for top per formances, discounts on bikes and parts for deserving riders, and on-site technical support at the major races.

Kawasaki's Team Green program, begun in 1980, is the most compre hensive. Today, there is $2.1 million in its kitty for all amateur racers, $125,000 of which-$600 per win-is earmarked for the four "national" am ateur events in 1997. In addition, Team Green provides four box vans for on-site support at 200 events around the country. Staffers are on hand to lend free technical assistance for anyone riding a Kawasaki.

Team Green's semi-factory sponsor ship program numbers 100 riders and comes in two forms: assist and sup port. Assist rides include discounted bikes and parts, and in some cases a parts allowance. Support rides vary from even deeper discounts on bikes and parts to full factory support-just like the Pro riders minus the mechan ic, team semi and big salary.

Suzuki operates a similar support program that boasts a $2.5 million overall amateur payout, and fields two box vans that show up at 70 events throughout the year.

Yamaha has $2.1 million available in its amateur coffers, with on-site support pro vided by local dealers.

As mentioned, KTM is also in the amateur support business, with savings bonds, bike purchase deals, parts allowances and sup port rides.

Honda, which has offered sporadic amateur motocross support since it intro duced the ground-breaking XR75 in 1974, recently dropped a bombshell: In a drastic move, the company dis banded its three-rider "factory" team and its contingency program in search of better ways to use the money. "We've been looking at contingency programs over the last few years to de termine if they're doing what we set out to do with them," explains Honda's Gary Christopher. "We found that the bulk of the money went to a small handful of people. In our opinion, we weren't doing what we intended to do. So, we decided to support all of mo torcycling in a number of different ways with other programs." To date, there is no official word on how that money will be spent.

That comment underscores a con troversy currently raging in mini-mo tocross: Is all the money and support doing more harm than good?

None other than Bob Hannah, a sixtime national champion who didn't race until he was 18, votes yes. "Some of `em are spoiled rotten," he says. "When they get a factory ride, they go down hill-there's nobody to wipe their butts, clean their helmets and mount their tear-offs. If I were making the rules, I wouldn't let `em into professional rac ing until they were 18. Or I'd recom mend that the factories not hire `em until they finish school. If you can't do that, you have no gumption whatsoever; hell, it takes an idiot to finish high school nowadays. If it was up to me, there wouldn't be any such thing as a factory mini rider. Nobody would get anything for free until they were 18."

"I think the factory involvement has hurt the sport~' agrees Dean Dickson, a hop-up shop owner who's been around mini racing for more than 20 years. "The kids aren't as driven or competitive today because so much is given to them; they don't have to earn it anymore."

Jeff Ward begs to differ~ The seventime national champion started racing at age 5 and made $1000 per week when he was 12 years old. The money didn't seem to spoil him, evidenced by a stel lar, 16-year Pro career. The one-time "Flying Freckle" fires back that there are two different types of mini racers. "For one kid," Ward says, "the money goes to his head. He parties all the time and burns out when he's 19. Then, there are those who don't care about the money, they just want to win. That was me. Money just wasn't the issue."

A generation later, though, the same may not be the case. Mini sensation Ricky Carmichael recently signed a contract with the factory-backed Pro Circuit team and made an impressive professional debut at just 17 years old. Commenting on his success, the nine time amateur national champion says, "I missed going out with friends on weekends, but I look forward to my re tirement. If things work out, I'll be able to party from the time I'm 30. Hope fully, I'll never have to work again."

The debate over factory mini riders and bulging corporate budgets, it seems, will go on as long as there are kids shooting for the stars and parents willing to push them to those heights.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue