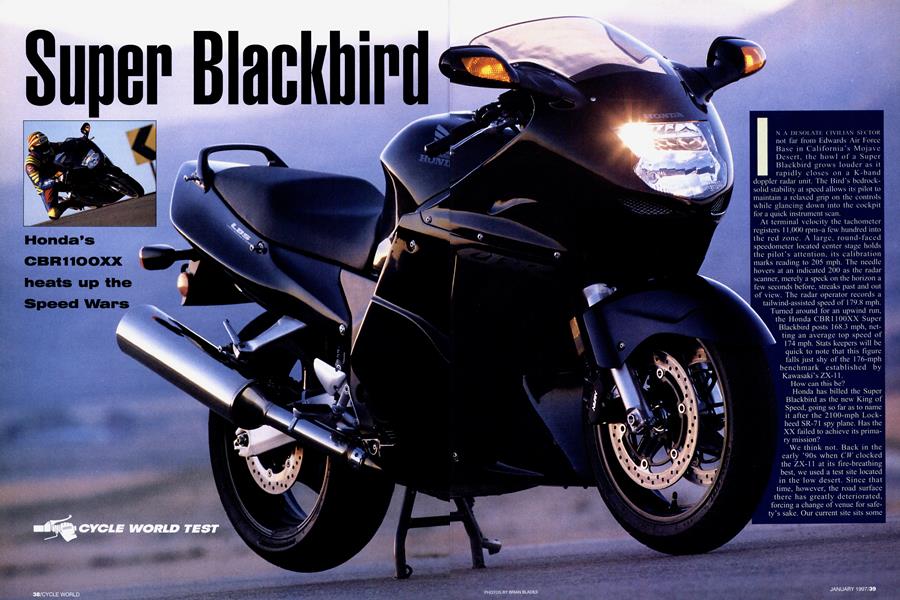

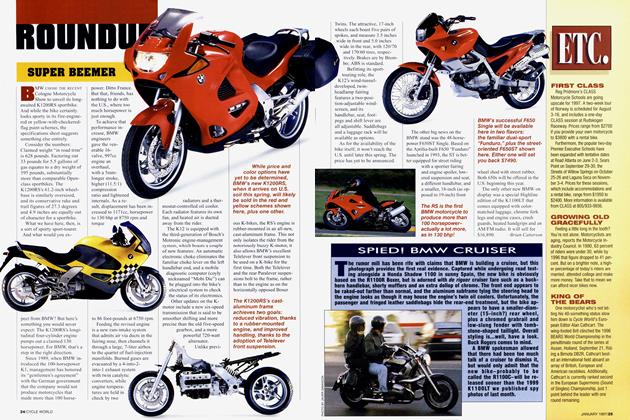

Super Blackbird

Honda’s CBR1100XX heats up the Speed Wars

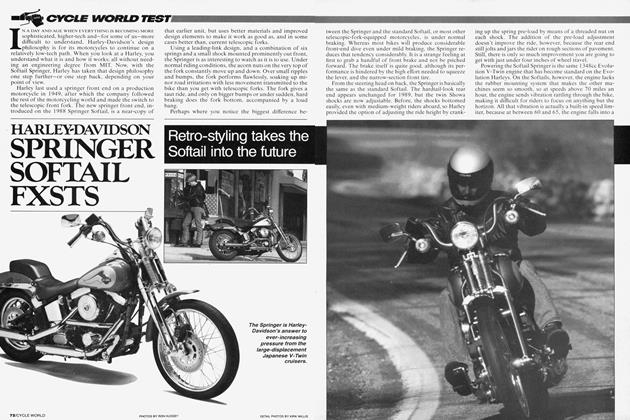

CYCLE WORLD TEST

IN A DESOLATE CIVILIAN SECTOR not far from Edwards Air Force Base in California's Mojave Desert, the howl of a Super Blackbird grows louder as it rapidly closes on a K-band doppler radar unit. The Bird's bedrocksolid stability at speed allows its pilot to maintain a relaxed grip on the controls while glancing down into the cockpit for a quick instrument scan.

At terminal velocity the tachometer registers I 1,000 rpm-a few hundred into the red zone. A large, round-faced speedometer located center stage holds the pilot’s attention, its calibration marks reading to 205 mph. The needle hovers at an indicated 200 as the radar scanner, merely a speck on the horizon a few seconds before, streaks past and out of view. The radar operator records a tailwind-assisted speed of 179.8 mph. Turned around for an upwind run, the Honda CBR1 100XX Super Blackbird posts 168.3 mph, netting an average top speed of 174 mph. Stats keepers will be quick to note that this figure falls just shy of the 176-mph benchmark established by Kawasaki’s ZX-11.

How can this be?

Honda has billed the Super Blackbird as the new King of Speed, going so far as to name it after the 2100-mph Lockheed SR-71 spy plane. Has the XX failed to achieve its primary mission?

We think not. Back in the early ’90s when CW clocked the ZX-11 at its fire-breathing best, we used a test site located in the low desert. Since that time, however, the road surface there has greatly deteriorated, forcing a change of venue for safety’s sake. Our current site sits some 2000 feet higher in elevation, resulting in a 2to 4-mph-lower reading on fast machines. It looks like a top-speed toss-up, then, until we can arrange a heads-up showdown between these two powerhouse machines.

There’s little doubt that gunning down the ZX-l l was a principal design goal when development began on the Super Blackbird in 1994. But, slated as replacement for the aging CBR1000F, the new CBRl 100XX also had to excel as a civil, well-rounded sport-tourer.

With this in mind, the first order was to minimize engine vibration. Honda engineers tackled tingles at the source rather than resorting to rubber-mounting the engine, bars or footpegs. The XX’s l I37cc inline-Four is very similar in design to those of the CBR600F3 and CBR900RR, featuring a unitary upper crankcase and cylinder-block configuration, side-mounted cam drive and compact, shim-under-bucket valvetrain. The major difference comes in the form of two geardriven counterbalancer shafts that effectively pare secondary vibrations to a mild high-frequency buzz barely felt through the bars and pegs. The new engine is claimed to weigh 22 pounds less than the CBR1000 mill, and is visibly more compact.

With the engine serving as a stressed member in the black-anodized, twin-spar aluminum frame, designers met their chassis-rigidity goal while keeping weight to a minimum. Frame construction is very similar to that of the 900RR, with large, triple-box-section, extruded-aluminum main spars welded to a cast steering head and webbed, die-cast-aluminum swingarm-pivot plates. The swingarm is also constructed of triple-box-section extruded aluminum, while the seat section is supported by a bolt-on steel subframe. Tipping our scales at a fairly portly 526 pounds without fuel, it’s clear that weight savings in one area have been somewhat offset by the additional components related to Honda’s Linked Braking System (more on this later) and twin-muffler 4-2-1-2 exhaust system. Still, you can get away with packing on a few extra pounds if you’re sporting the ponies to pull it.

Dyno results show the XX engine to be the strongest of any current production bike, producing a peak reading of 135 rear-wheel horsepower at 9500 rpm, with 79 footpounds of torque at 7500 rpm.

In our last issue, we reprinted a riding impression by England’s Performance Bikes magazine that called the CBRl 100XX motor “flat as a pancake right were you need it the most, between 5000 and 6000 rpm.” Our findings concur that a slight dip in the torque curve does exist. But lacking in midrange? Not a chance.

Low-end power is exceptionally strong. The XX’s topgear roll-on performance of 3.2 seconds from 40-60 mph makes it nearly a full second quicker than the ZX-l 1. Between 4000 and 6000 rpm, the aformentioned power dip blunts the Bird’s progress slightly, but’s it’s still three-tenths of a second quicker from 60-80 mph than the big ZX. In any event, working the Bird’s gearbox is seldom, if ever, necessary for traffic-erasing passes.

Carburetion is crisp under any load or rpm. Snapping the throttle open in low gear yanks the front wheel skyward in a B-I-G way. Simply rolling the twistgrip to the stops from low rpm results in a smoother, albeit similar, outcome, the front end lifting in a progressive power wheelie as the revs spin up through 6500 rpm. Not surprising, really, because between 6000 and 7500 rpm, there’s an attention-getting 34-horsepower swell.

Clutch action is smooth with good feedback, and the pack held up to our usual dragstrip abuse without complaint. Although at 58.7 inches, the Blackbird’s wheelbase isn’t particularly short, keeping the front wheel down during hard launches took some effort. Get it right and the XX’s 2.6-second 0-60-mph acceleration will have you swallowing your chewing gum if not prepared. Once again, we found ourselves aiming for the ZX-l 1’s all-time low quarter-mile ET of 10.25 seconds at 137 mph, set back in 1990. The Blackbird came very close: 10.27 seconds at 136 mph with a pair of 10.30and 10.31-second runs to back it up. Also, it should be noted that our more recent ZX-l 1 testbikes have produced runs “only” in the mid-10s.

For an Open-class sport/GT bike, the 1100XX carries its weight well. In low-speed handling and parking-lot maneuvers, it feels like a middleweight. At speed, the XX is a great deal more agile than the CBR1000 it replaces, with suspension sprung firmly enough and well damped enough to maintain chassis control when ridden at a fast clip through the canyons. Steering is neutral; even when trailing the brakes into corners, the bike doesn’t stand up in the least. Hard cornering will have the peg feelers trailing sparks and the fairing lowers next in line to touch down. The centerstand is tucked up nicely, adding convenience without extracting a price in cornering clearance.

The cartridge fork has no external adjusters, while the rear shock only has adjustable rebound damping. Altering the shock’s spring preload requires a hammer and punch, as its threaded collar is tucked up within the framework and not easily accessed. A ramp-type adjuster would have been much more appropriate on a bike that will likely see a mixture of solo and two-up use.

As delivered, the suspension is calibrated more toward sporting duty than commuting or touring. The rear delivers a harsh ride over freeway joints, while the riding position is closer to that of a CBR900RR than a VFR750F.

Honda has fitted the CBR1100XX with a revised Linked Braking System (LBS). This ties the front and rear systems together so that independent application of either the hand or foot lever results in braking force generated at both wheels. In panic situations, many riders tend to stand on the rear brake and forget the front altogether. LBS dramatically improves stopping performance in such a case. Our testing showed hard stops made solely with the foot pedal to be 165 feet from 60 mph, far better than a conventional system. Repeating the test using only the front lever produced a distance of 140 feet, while applying both controls together hauled the bike down in 126 feet. Earlier LBS plumbing fitted to the 1993-96 CBRIOOO and to last year’s ST 1100 drew complaints for being too sensitive, causing the fork to dive abruptly even when the brakes were applied gently. Honda has addressed the problem by adding a delay valve between the rear pedal and the right-front caliper, giving the XX smoother, more progressive braking response. The system’s overall feel is like that of power brakes on a car and takes a bit of getting use to, but there’s no arguing that LBS works-clamp on both binders and the Honda simply hunkers down and stops, no fuss, no muss.

In the end, it’s hard to call the Super Blackbird the new Sultan of Speed. It’s certainly not the 180or 185-mph ZXkiller early hype all but promised. Still, for Kawasaki, a company that hangs its hat on high performance, the XX is clearly too close for comfort. A retaliatory strike in the form of a bigger, better, badder Ninja surely is on the way. It’s only a matter of time before the desert silence is once again broken by the sound of a big Four wailing at redline.

Our radar operators are standing by. □

EDITORS' NOTES

“HOW FAST HAVE YOU GOTTEN ’ER UP to?” Better get used to answering that question if you’re considering a Super Blackbird as your next purchase. If the bike’s swoopy looks or distinctive name don’t raise the question, then its not-so-subtle 205-mph speedo should capture Joe Public’s attention.

Which raises another point. The ZXH’s speedometer only registers to 200 mph-it would seem the Blackbird already has it beat among the less-informed tire-kickers in the parking lot. But even if you never come close to pressing the edge of its performance envelope, the XX provides plenty to talk about. From its nimble handling to its powerful linked braking system to its stunning blacked-out styling, there’s a lot to like here.

Besides, when it comes to top speed, better to quote magazine articles than spin the dials yourself. That is, unless becoming a Super Jail Bird holds a certain appeal.

-Don Canet, Road Test Editor

BACK IN 1990, CW EDITORIAL DIRECTOR Paul Dean went 176 mph on Kawasaki’s then-new ZX-11, making it the fastest production motorcycle you could buy.

Always one for a little inter-office rivalry, I had high hopes of topping Dean’s mark on Honda’s 135-horsepower CBR1100XX Super Blackbird. Along with a dozen other members of the press, I made four, throttle-to-the-stop laps aboard the Blackbird at American Honda’s 7.5-mile desert test oval. But despite my tucked-in, helmet-on-the-tank riding position and a go-for-broke drive off the final sweeping comer, all I could manage was 175 mph.

Even our in-house fast guy, Road Test Editor Don Canet, couldn’t find the needed speed. A few days later in decidedly more difficult conditions, Canet barely struggled to an official two-way average of 174 mph.

So, Dean and Kawasaki still have bragging rights. As for Canet, well, I guess I’m a hair faster-if only in a straight line.

-Matthew Miles, Managing Editor

NICE BIKE, SHAME ABOUT THE BRAKES. Not that there’s anything wrong with Honda’s second-generation Linked Braking System, because there isn’t. It’s just a question of necessity.

Honda makes no bones about LBS being a concession to inexperienced riders. And while company personnel agree that the 174-mph Super Blackbird is an expert’s bike, they’re quick to point out that experts aren’t the only ones who’ll buy one.

Personally, I don’t believe that the possibility of some squid standing on the rear brake pedal when he gets in trouble warrants fitting LBS. And I don’t buy a certain Honda R&D tester’s rationalization that even experienced riders will lock the rear brake in a panic situation. If that was the concern, why not fit rear-wheel ABS? Pickups and vans have had ’em for years.

The way I figure it, the CBR carries an “XX” designation on its flanks for a reason: It’s for mature adults only. Maybe it ought to read “NC-17.”

-Brian Catterson, Executive Editor

HONDA CBR1100XX

$10,999

View Full Issue

View Full Issue