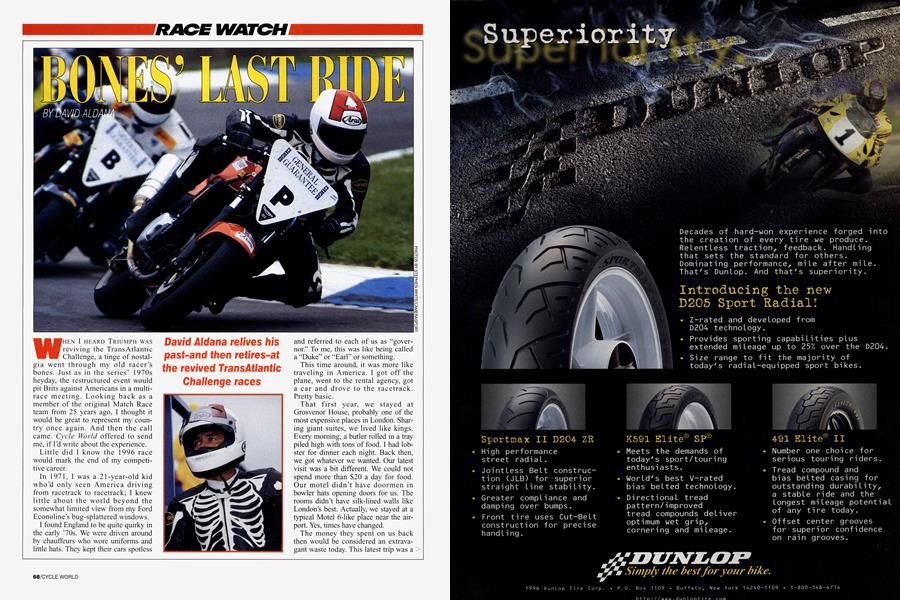

BONES' LAST RIDE

RACE WATCH

David Aldana relives his past-and then retires-at the revived TransAtlantic Challenge races

DAVID ALDANA

WHEN I HEARD TRIUMPH WAS reviving the TransAtlantic Challenge, a tinge of nostalgia went through my old racer’s bones. Just as in the series’ 1970s heyday, the restructured event would pit Brits against Americans in a multirace meeting. Looking back as a member of the original Match Race team from 25 years ago, I thought it would be great to represent my country once again. And then the call came. Cycle World offered to send me, if I’d write about the experience.

Little did I know the 1996 race would mark the end of my competitive career.

In 1971, I was a 21-year-old kid who’d only seen America driving from racetrack to racetrack; I knew little about the world beyond the somewhat limited view from my Ford Econoline’s bug-splattered windows.

I found England to be quite quirky in the early ’70s. We were driven around by chauffeurs who wore uniforms and little hats. They kept their cars spotless

and referred to each of us as “governor.” To me, this was like being called a “Duke” or “Earl” or something.

This time around, it was more like traveling in America. I got off the plane, went to the rental agency, got a car and drove to the racetrack. Pretty basic.

That first year, we stayed at Grosvenor House, probably one of the most expensive places in London. Sharing giant suites, we lived like kings. Every morning, a butler rolled in a tray piled high with tons of food. I had lobster for dinner each night. Back then, we got whatever we wanted. Our latest visit was a bit different. We could not spend more than $20 a day for food. Our motel didn’t have doormen in bowler hats opening doors for us. The rooms didn’t have silk-lined walls like London’s best. Actually, we stayed at a typical Motel 6-like place near the airport. Yes, times have changed.

The money they spent on us back then would be considered an extravagant waste today. This latest trip was a low-budget affair. Most of my teammates didn’t get any appearance money from the promoters. They were thankful to have their air and ground travel taken care of, but the rest came out of their pockets. In fact, a few said the trip cost them $200-300.

The minute I leave my house for a race, it’s work. My income tax guy says, “If you don’t make any money, it’s a hobby; if you make money, you have to pay taxes.” In better years, I was paid $12,000 just to show up. Compared to, say, Kenny Roberts, who was getting $25,000, I considered myself underpaid. But, hey, he was the world champion.

Because the old Match races were originally put on, in part, by my sponsor at the time, BSA/Triumph, the company put all of us on almost identical works bikes. These inline-Triples were pedigreed racing motorcycles; simply, we were on the best equipment available. In later years, when the event wasn’t brand-specific, the sport’s top riders brought out the trickest hardware the factories had to offer. We started out on the Triples, moved on to the early Formula 750 two-strokes, big Formula One bikes, and then, full-on works 500cc grand prix bikes were thrown in the mix.

This time, we rode race-kitted Triumph Speed Triples. To put it kindly, these streetbikes don’t make state-ofthe-art racebikes.

Before getting on the plane, I made a call to England and got my friend and longtime fan Andrew Fern, who has a ton of experience with Triumphs, to help with wrenching chores. He brought along his pal David Firnell. Without their help, the American team would have been in big trouble. Just imagine 15 guys working out of two small toolboxes.

We got the motorcycles on Saturday morning, theoretically giving us plenty of time to get them dialed-in for the race, which was to be held on Monday, England’s Bank Holiday. The bikes came from dealerships with all the street stuff taken off and tuned close to the 100-horsepower Speed Triple Challenge limit. All the bikes had a race exhaust, an oil cooler, an aftermarket shock, a steering damper and braidedsteel brake lines. But still, we had a lot of set-up work to do. We changed fork springs and adjusted ride height. We changed brake fluid and swapped gearing. And we replaced the engine oil to help break the transmissions in.

The experience that David McGrath and Scott Zampach have racing these bikes in America’s NASB Speed Triple series was invaluable. Nonetheless, it took us until race day just to make the bikes work decently. In comparison, the British riders and bikes were ringers. The guys were riding their personal bikes, on which they regularly compete in their own Speed Triple series, so they were already dialed-in.

We constantly messed with the front suspension to get the bikes to stop wiggling on Donington’s wavy straightaway. I got in such violent wobbles that I couldn't keep the throttle pinned or even think about drafting.

Unlike past events, which were held on three different racetracks, we rode in an intense one-day, three-race format at Donington Park. The old threetrack formula was a better deal that gave the Americans a chance of doing well. For instance, Oulton Park, the last track we used to visit, was a course the Brits saw only once or twice a year. This didn’t give them a chance to have it dialed like they did Donington.

On Monday, we were greeted by typical British weather. During timed qualifying it was raining, and unfortunately, I was more concerned about tipping over and making an ass out of myself than getting a good starting > spot. I stayed out of trouble, but carded a sixth-row grid position. Zampach, our team captain, and Tripp Nobles were the only Americans to qualify in the top 10.

In the good oT days, we started with a waving flag. You could roll a bikelength or two and the startled starter would just throw the flag because everyone was already rolling. That was not the case this time, as a starting light was used. When it went from red to green, all 26 of us charged toward the narrow first turn.

Even though I failed to break into the top 10 in any of the races, I had a front-row seat for the action.

Nobles, who rides the Speed Triple Challenge at home, led into the first turn on the damp track in the opening race. I was amazed; these guys were really going for it while fighting over the dry racing line. I never saw so much bumping, so much nerfing and so many almost crashes. In America, we would be suspended for this kind of riding. By lap three, the Brits took control, with team captain Mark Phillips, the 1995 U.K. Speed Triple series winner, being overtaken by teammate Paul Brown before the end. Zampach placed second, while the American trio of David McGrath, Sadowski and Nobles took sixth through eighth. Meanwhile, I rode around near the back of the pack waiting for the checkered flag to fly. Hey, I was just glad to finish my first real sprint race in 11 years.

The track dried out considerably for race two, and the start was wild. I was in 10th before being taken out and landing in a gravel trap. The guy who hit me probably didn’t know I was there until we made contact, then it was too late! This incident took out several bikes, brought out a red flag and sent McGrath to the sidelines with a broken shoulder. After I paddled my way out of the gravel, Brown led the restart and stayed up front until the end. Our best scorers were Zampach in fourth and Nobles in seventh. Sadowski, who finished 13th, posted the fastest lap of the race after an off-track excursion of his own. I began to loosen up, but still finished way down in the pack. It was during this race that I felt the urge to retire creeping up on me.

While we rode on a completely dry track in race three, I circulated in a comfortable position-near the back, but not the final bike in the freight train. Zampach led early on, but it was Sadowski who came alive at the twothirds mark and saved face for the American squad by taking the win.

Thankfully, I never got lapped and came out as the top-scoring “journalist,” beating Cycle World’s European Editor Alan Cathcart and Motorcyclist’s Kent Kunitsugu. In spite of our efforts, the Brits outscored us 614 to 426.

After our defeat, I reflected on the “team” concept. In years past, we relied upon group strategy; this time around, it was every man for himself.

In the ’70s and ’80s, we Americans stayed together and used up as much of the racetrack as we could. But if

one of us was capable of catching up and dicing for the lead, we let him go.

For these resurrected races, there was less pressure to perform and a noticeable difference in the crowd. Years ago, what seemed like hundreds of thousands of fans would line all three tracks. Here at Donington, there couldn’t have been more than 10,000 people. I know there were at least a few American fans this time, because I saw them holding up a single red-white-and-blue flag.

But I won’t be waving our flag again in anger-the 1996 TransAtlantic Challenge races will mark my last time in true competition. Yup, that’s it, I’m hanging up my “Bones” leathers. There’s just no way in the world I can ride at top level anymore. When I was younger, there were no obstacles; now, there are many.

Sometimes at Donington I was more concerned with not falling off and embarrassing myself than with cutting quicker laps. Risking life and limb, a racer can’t possibly have this on his mind. I realized that I’m not the racer I used to be. Sure, I went as fast as the others for a lap or two, but when it came to squeezing my handlebars between one rider’s leg and another’s exhaust pipe, I just don’t have what it takes to do this lap after lap.

After an early practice session, American Chuck Graves came over and put his arm around my shoulder and said, “For an old fart, you’re not too bad.” This made me feel accepted, glad that I wasn’t just a token race fossil. This was the highlight of the weekend for me. In my mind, I had accomplished what I set out to do-score some points for the American team and not embarrass myself. But, clearly, it was time to hang ’em up.

I wish the Match Races would attract all the sport’s greatest talent again, but the glory days of the ’70s and ’80s are over. After Freddie Spencer was injured during a Match race at Donington in 1983 and almost lost the GP title, grand prix bikes and top factory guys were never again seen at this non-championship event. This lack of top talent put the Match Races on hiatus for the past 13 years. I would like to see the Americans go to Britain again. Better yet, let them come here and face the same one-off race situation on unfamiliar bikes as we did. Yeah, put ’em on good oT Harley 883s against our top SuperTwins riders at Laguna Seca, and then see where the chips fall. Now, that would be interesting! □

One of the most versatile racers this country has produced, David Aldana, 46, started racing in 1968. He rode for the BSA, Honda, Kawasaki, Norton, Ossa and Suzuki factory teams. Aldana led the Americans to victory at the 1975 Match Races, garnered a WERA endurance title, scored wins in AMA roadrace and dirt-track competition and won the Suzuka 8-Hours. Today, he is the head instructor at the Team Suzuki Endurance Advanced Riding School. When not at the racetrack, Aldana spends most of his time breeding and training racing pigeons.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMillion Mile Man

September 1996 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsMinibike Flashback

September 1996 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCRising Duty

September 1996 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1996 -

Roundup

Roundup1997 Honda Cbr1100xx Super Blackbird Sighted

September 1996 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

RoundupSupercross Superbike

September 1996 By Jimmy Lewis