LAST RIDE TO THE LOST CITY

A scam, a sham and a foolhardy plan

OLD WEST FOLKLORE holds that in 1873, a group of stagecoach robbers, hot off a Wells-Fargo heist, fled up Surprise Canyon on the western edge of Death Valley. There, hiding out in an isolated gulch 7000 feet up a mountain bordering Panamint Valley, the bandits found the hills rich with silver.

Now the bandits couldn’t hide out forever, but they didn’t want to go to jail, either. So they did what any self-respecting criminal would do: They bribed the authorities.

A sample of the ore was sent to Nevada Senator William Morris Stewart, who was given an option to purchase the bandits’ claim for just $20,000-provided he could settle their score with the law. The senator agreed to the bandits’ terms and became the proprietor of a silver-mining operation-an investment scam that built Panamint City.

More than a century later, President Clinton signed into law a bill that may have as much impact on the area as the discovery of silver. Senate bill S21, the Desert Protection Act, set aside 7.5 million acres of California public land as new wilderness areas and established two new National Parks and a National Preserve, which incorporated Panamint City into the Death Valley National Park.

Unfortunately, the measure dealt yet another unneeded blow to off-road motorcyclists. With vehicular travel already restricted to street-licensed machines sticking to established “roads” within park boundaries, the bill allows the Park Service to declare lesser routes “unmaintainable” and close them to all but hikers and horses. Fearing that this fate might befall the road to Panamint City, we decided to make the journey while we still had the chance.

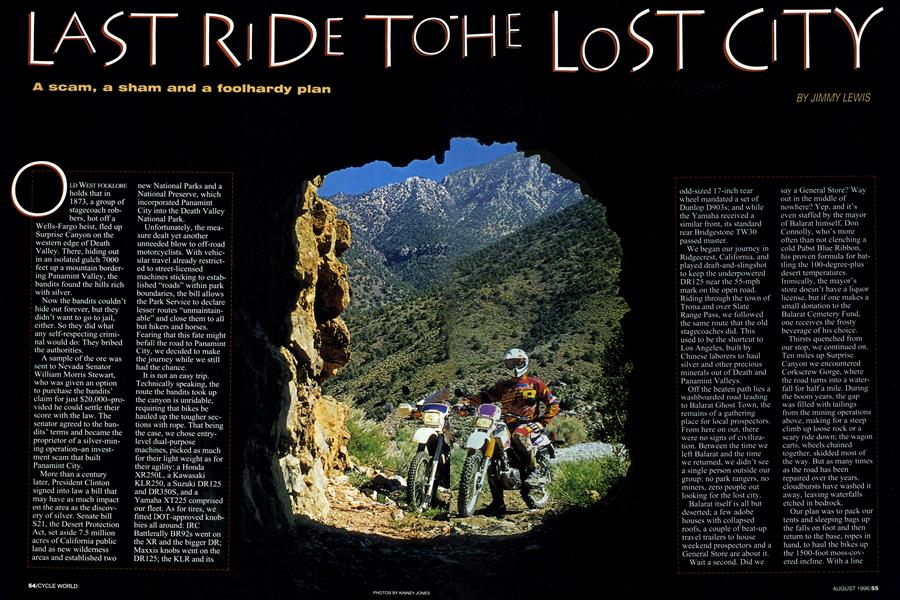

It is not an easy trip. Technically speaking, the route the bandits took up the canyon is unridable, requiring that bikes be hauled up the tougher sections with rope. That being the case, we chose entrylevel dual-purpose machines, picked as much for their light weight as for their agility: a Honda XR250L, a Kawasaki KLR250, a Suzuki DR 125 and DR350S, and a Yamaha XT225 comprised our fleet. As for tires, we fitted DOT-approved knobbies all around: IRC Battlerally BR92s went on the XR and the bigger DR; Maxxis knobs went on the DR 125; the KLR and its odd-sized 17-inch rear wheel mandated a set of Dunlop D903s; and while the Yamaha received a similar front, its standard rear Bridgestone TW30 passed muster.

JIMMY LEWIS

We began our journey in Ridgecrest, California, and played draft-and-slingshot to keep the underpowered DR 125 near the 55-mph mark on the open road. Riding through the town of Trôna and over Slate Range Pass, we followed the same route that the old stagecoaches did. This used to be the shortcut to Los Angeles, built by Chinese laborers to haul silver and other precious minerals out of Death and Panamint Valleys.

Off the beaten path lies a washboarded road leading to Balarat Ghost Town, the remains of a gathering place for local prospectors. From here on out, there were no signs of civilization. Between the time we left Balarat and the time we returned, we didn’t see a single person outside our group: no park rangers, no miners, zero people out looking for the lost city.

Balarat itself is all but deserted; a few adobe houses with collapsed roofs, a couple of beat-up travel trailers to house weekend prospectors and a General Store are about it.

Wait a second. Did we

say a General Store? Way out in the middle of nowhere? Yep, and it’s even staffed by the mayor of Balarat himself, Don Connolly, who's more often than not clenching a cold Pabst Blue Ribbon, his proven formula for battling the 100-degree-plus desert temperatures. Ironically, the mayor’s store doesn’t have a liquor license, but if one makes a small donation to the Balarat Cemetery Fund, one receives the frosty beverage of his choice.

Thirsts quenched from our stop, we continued on. Ten miles up Surprise Canyon we encountered Corkscrew Gorge, where the road turns into a waterfall for half a mile. During the boom years, the gap was filled with tailings from the mining operations above, making for a steep climb up loose rock or a scary ride down; the wagon carts, wheels chained together, skidded most of the way. But as many times as the road has been repaired over the years, cloudbursts have washed it away, leaving waterfalls etched in bedrock.

Our plan was to pack our tents and sleeping bags up the falls on foot and then return to the base, ropes in hand, to haul the bikes up the 1500-foot moss-covered incline. With a line attached to each fork le”' someone to operate the;g? bikes’ controls, a pushi “mule” and an adverse-ng event corrector, we we> ready to “ride” up the fre

Generally, we couldalls-

enough traction to get §et

front wheel going

upward. Then, it was 1

to our hired muscle mJ^

en

Scott Scarborough ancj Marko Henricksen, to provide power. Staffers David Edwards and Matthew Miles played the role of pushing mules, Miles taking his fare share of wet, mossy roost in the line of duty.

Despite the fact that each section was more challenging than the last, I attempted to keep my companions’ spirits up by telling them that it was getting easier. Heck, you don’t tell your camel that there’s no water in the oasis! So after nearly three hours of playing tug of war, we managed to ascend the falls.

Our work wasn’t over, however. Packed to the hilt with camping supplies, we had to conquer 6 more miles of rocky road before seeing the old Panamint smokestack that marked our destination. The

increase in elevation did nothing to help our little bikes’ performance, either; 200-pound Miles and his gearbag posed a real challenge for the DR 125. The limits of man and machine were thoroughly tested, but both eventually made it.

Throughout the trip, we renewed our respect for the $3799 XT225 as a competent entry-level bike that can do way more than expected. We were also pleasantly surprised with the $4499 DR350S: Pushbutton electric starting escalates it to a new level in the dual-purpose ranks. The $4299 XR250L worked as well as ever, though we have to wonder when it will get the magic button. The $3899 KLR250 did everything well and nothing badly, though its pavement heritage is evident in the dirt. The $3299 DR 125 completed the journey, but with very low marks. Its severe lack of power frustrates skilled riders and demands extra attention from beginners. The new-for-’96 DR200 would have been a better choice for this trip.

With a hard day’s work behind us, the remains of a “town” came within sight.

It was immediately apparent that there was little left of the main street that was once home to some 2000 miners. The old rock foundations remain, but the sage brush has grown higher than the crumbling walls.

All around the city, mining operations old and new can be found; we even rode half a mile into the Wyoming mine. A few cabins still stand about the valley: some old and dilapidated, some newer and in

excellent condition, rats notwithstanding.

Tales of Panamint City’s history become more intriguing when confronted by physical evidence. It seems that the founding bandits had a much larger plan for Panamint’s silver: They would wait, then continue their wayward manners, stealing the precious mineral as the stagecoaches ran down to Balarat. Knowing better, mine operators molded the silver into huge balls weighing as much as 750 pounds-way too heavy to steal.

In 1876, after only three years of operation, the ore began to run out. That same year, a flash flood washed out the road. Coincidentally, the smelting mill-which, of course, was well-insuredbumed to the ground, leaving only its brick smokestacks. These events prompted Senator Stewart to report a “large loss” to his investors, though it is said that more than $ 1 million worth of silver came from Panamint City.

Returning to Balarat the next day, we met up with Mayor Connolly again, who told us that he’s confused by the Desert Protection Act. “No one asked me what I thought, and I live here,” he proclaimed. “You ought to see what they’re going to be doing right down the road to ‘protect the desert.’ From what I can tell, they’re going to test the effects of dynamite blasts on the colony of bighorn sheep that live in the canyon right above the strip mine. Now that ’s protection.”

Hypocrisy? Panamint City has withstood more than 100 years of mining, preserving itself by turning all but the hardiest folks away at Corkscrew Gorge. Yet, for reasons apparent only to politicians, this area needs legislative protection? We managed to meet our goal of riding to Panamint City, but left fearing that someday soon a red sign with the words “Route Closed” will mark the turnoff to Surprise Canyon. Could this have been the last ride to the lost city?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue