AMERICAN Grand Prix STYLE

RACE WATCH

THE CATALINA GP COULD HAVE BEEN OUR ISLE OF MAN. IT STILL MAY BE.

ERIC PUTTER

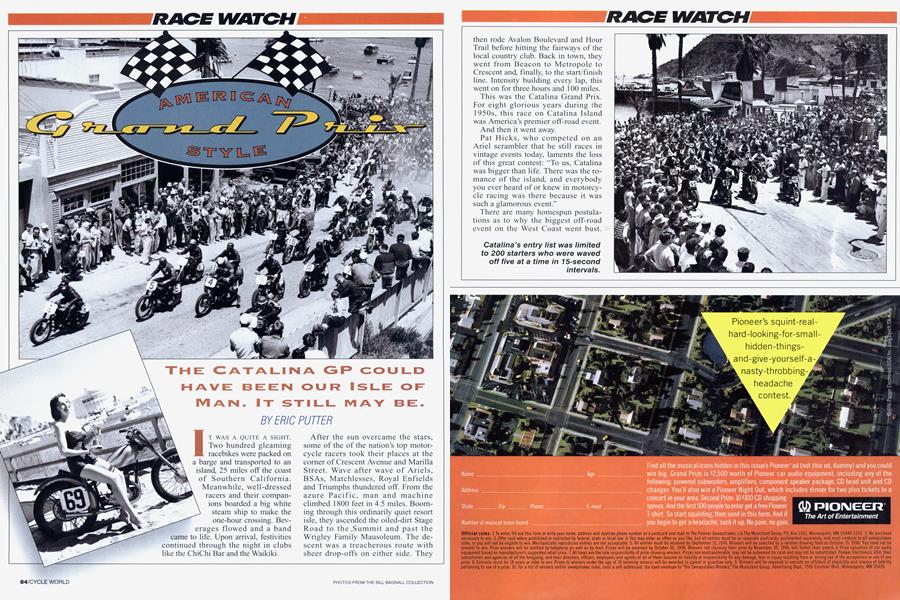

IT WAS A QUITE A SIGHT. Two hundred gleaming racebikes were packed on

a barge and transported to an island, 25 miles off the coast of Southern California. Meanwhile, well-dressed racers and their companions boarded a big white steam ship to make the one-hour crossing. Beverages flowed and a band came to life. Upon arrival, festivities continued through the night in clubs like the ChiChi Bar and the Waikiki.

After the sun overcame the stars, some of the of the nation’s top motorcycle racers took their places at the corner of Crescent Avenue and Marilla Street. Wave after wave of Ariels, BSAs, Matchlesses, Royal Enfields and Triumphs thundered off. From the azure Pacific, man and machine climbed 1800 feet in 4.5 miles. Booming through this ordinarily quiet resort isle, they ascended the oiled-dirt Stage Road to the .Summit and past the Wrigley Family Mausoleum. The descent was a treacherous route with sheer drop-offs on either side. They then rode Avalon Boulevard and Hour Trail before hitting the fairways of the local country club. Back in town, they went from Beacon to Metropole to Crescent and, finally, to the start/finish line. Intensity building every lap, this went on for three hours and 100 miles.

This was the Catalina Grand Prix. For eight glorious years during the 1950s, this race on Catalina Island was America’s premier off-road event. And then it went away.

Pat Hicks, who competed on an Ariel scrambler that he still races in vintage events today, laments the loss of this great contest: “To us, Catalina was bigger than life. There was the romance of the island, and everybody you ever heard of or knew in motorcycle racing was there because it was such a glamorous event.”

There are many homespun postulations as to why the biggest off-road event on the West Coast went bust. >

Some suggest it was the dark element of outlaw motorcycle gangs overrunfling the island, but Burr Dean, who raced a "fire-breathing" BSA Spitfire in 1957, discounts this, theory. "Yeah, the Galloping Gooses, Hell's Angels and Satan's Slaves were all there, but they didn't cause too much trouble because they were outnumbered by the racers. They were a small minori ty,s.

Retired stuntman Bud Ekins, the 1955 winner, recently came upon what he considers the true cause of Catalina's cancellation. He says, "There's only one way to put a course over there, and that's to go by an old folks' home. When that place went in, that was the end. Catalina will never happen again."

Since the island race, more GPs came and went, a few thrive today, and a cou ple are in the throes of resurrection.

As Catalina was on its way out, another huge classic race was emerging. On land owned by Crash Corrigan, a Western movie actor from the 1930s and ’40s, the Corriganville GP was born. The site, which was seen in the closing scene of “The Lone Ranger” television show, was an active movie set throughout the race’s era. Just outside Los Angeles County’s northwest boundary in Simi Valley, the figureeight Corriganville course twisted its way around huge oak trees, ran through the area’s signature rocky faced hills and passed the hitching posts and oldtime facades of the movie set.

In 1965, Bob Hope bought the land, changing the name from Corriganville to-what else-Hopetown. While the comedian was never seen at the race bearing his name, it gathered enough steam to attract more than 1000 riders, including three-time 250cc World Champion Torsten Hallman in 1966.

Lyle Taylor remembers the Hopetown GP clearly. “My friends and I were jazzed to hear that Hallman was racing. We stood at Powder Puff Corner, where the two loops came together, waiting for him to come bar reling through. Much to our surprise, he came into the corner on the com pression release and then got back on the throttle. It was amazing to watch him as he smoothly lapped our best riders," Taylor says.

The Elsinore Grand Prix, made famous in 1971 by Steve McQueen in the movie On Any Sunday and on ABC’s “Wide World of Sports,” was the next big GP on the map. Held from 1967 to ’72, it kept the basic streetand-dirt premise of the Catalina GP intact. Nearly 2000 riders and 150,000 spectators swelled this sleepy little desert village, population 3850, about 70 miles south of Los Angeles. Riders roared through town, showing off the distinctive styles of their respective disciplines: motocrossers tentative on the pavement, going in slow with a foot down at the ready; flat-trackers coming in fast and smooth, feet up and flying; and the desert racers making up time on the short, dusty section that passed Pedro’s Taco Parlor.

There were other GPs held in unforgiving places like California City and Westlake, California; Tecate and Ensenada, Mexico; and another big one at Riverside Raceway. Supposedly, Tecate ground to a halt after revelers turned half the town to ashes. Hopetown is said to have been shut down because turkeys on a local ranch trampled one another to death when the bikes flew by. Elsinore was stopped in its track by lawsuits stemming from riders hitting fire hy> drants. Riverside was razed to make way for a shopping mall.

This year, seven motorcycle clubs in Southern California’s AMA District 37 will hold grand prix races. But in these litigious times, unfortunately, only the Adelanto GP actually takes over a small town. Most are named for and run around motocross tracks, making them long, glorified motos with sections of open desert or enduro-like single-track terrain thrown in for good measure. Still fun, but not in the same league as Catalina, Hopetown or Elsinore.

Maybe that will change. Contrary to popular opinion, Catalina might be on its way back. Stu Peters, now a major regional race promoter, competed in the island GP during its final two years, and is attempting to resurrect the classic event. Peters admits to having recent meetings with key Catalina business people. He reports that the island desperately needs some income during its off season He is in the planning stages of bringing both a motocross and a grand prix to the island sometime in the spring of 1997.

While whispers of a revived Catalina GP are being heard, Elsinore was put back on the map recently. Former factory Kawasaki motocrosser and current race promoter Goat Breker just convinced the city of Elsinore that it needs motorcycles once againas well as watercraft, mountain bikes and runners-to rouse it from a deep economic slumber. The resurrected event is being billed as the “Elsinore Grand Prix and Outdoor Sports Classic.”

Mayor Kevin Pape looks forward to bringing motorcycles back to Elsinore. He says, “Business owners are excited to have more crowds so late in the season. I don’t see any roadblocks; there’s nothing that can’t be worked out.”

Other extreme activities planned are a motorcycle trials meet, a mountain bike race, a watercraft race on Lake Elsinore and a 5k foot race. Breker envisions crowning the participant who scores the most combined points in all events the “Grand Champion.”

Biggest sticking point was taking the race back to the heart of Elsinore. Breker insisted the event start on Main Street, just like in the ’70s. He says, “I’m so excited. If I pull this one off, it will be the biggest thing I can contribute to the sport.”

Demographics and conventional wisdom suggest that these resurrected races will be a hit. The AMA reports that the most requested race sanctions are for hare scrambles events, which are more or less GPs without pavement sections. Peters concurs: “With all the (motocross) classes we have now, people are tired of waiting around all day to race for 20 minutes; they want to save their money for special events.” Breker suggests that the fastest growing segments of the off-road racing market are the crusty Veteran and fresh-faced Youth class-> es-two divisions that could make the GP ranks swell once more.

Vet racer Jeff Maas, who comes from a California family steeped in the tradition of motocross and desert racing, says of the proposed Elsinore event, “It will be great to bring my son to a race that I missed as a kid. To me, the event itself is more important than the competition. When he gets older, we could watch On Any Sunday the night before and relive the past-together.” □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontNorton Boy

July 1996 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsTriumph Deferment

July 1996 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCIntake Flow 101

July 1996 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1996 -

Roundup

RoundupItalian Superbike Revival

July 1996 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupIs There A Stroker In Your Future?

July 1996 By Kevin Cameron