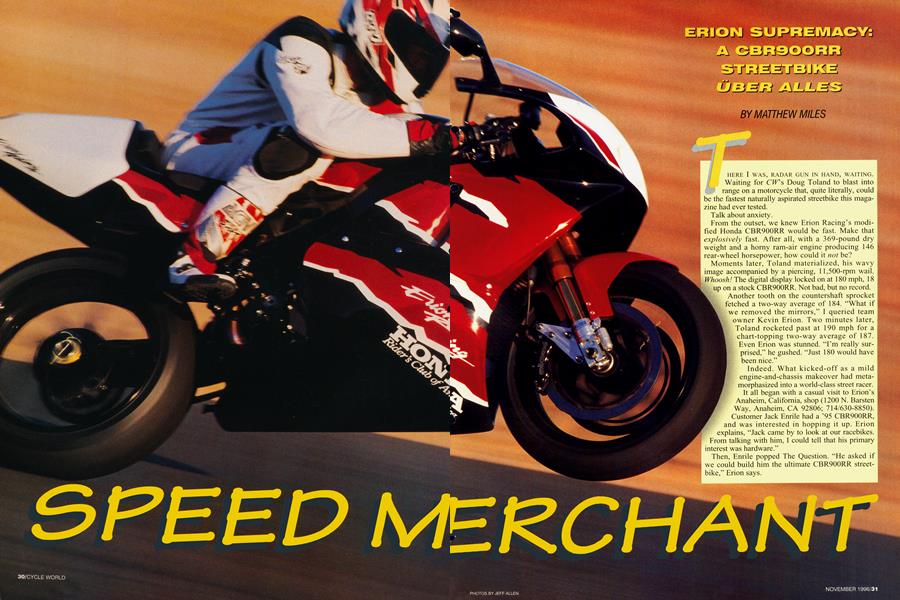

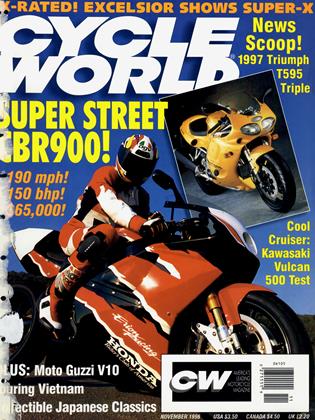

SPEED MERCHANT

ERION SUPREMACY: A CBR900RR STREETBIKE ÜBER ALLES

MATTHEW MILES

THERE I WAS, RADAR GUN IN HAND, WAITING. Waiting for CW's Doug Toland to blast into range on a motorcycle that, quite literally, could be the fastest naturally aspirated streetbike this magazine had ever tested.

Talk about anxiety. From the outset, we knew Erion Racing’s modified Honda CBR900RR would be fast. Make that explosively fast. After all, with a 369-pound dry weight and a horny ram-air engine producing 146 rear-wheel horsepower, how could it not be?

Moments later, Toland materialized, his wavy image accompanied by a piercing, 11,500-rpm wail. Whoosh! The digital display locked on at 180 mph, 18 up on a stock CBR900RR. Not bad, but no record. Another tooth on the countershaft sprocket fetched a two-way average of 184. “What if we removed the mirrors,” I queried team owner Kevin Erion. Two minutes later, Toland rocketed past at 190 mph for a chart-topping two-way average of 187. Even Erion was stunned. “I’m really surprised,” he gushed. “Just 180 would have been nice.”

Indeed. What kicked-off as a mild engine-and-chassis makeover had metamorphasized into a world-class street racer.

It all began with a casual visit to Erion’s Anaheim, California, shop (1200 N. Barsten Way, Anaheim, CA 92806; 714/630-8850). Customer Jack Enrile had a ’95 CBR900RR, and was interested in hopping it up. Erion explains, “Jack came by to look at our racebikes.

From talking with him, I could tell that his primary interest was hardware.”

Then, Enrile popped The Question. “He asked if we could build him the ultimate CBR900RR streetbike,” Erion says.

For Enrile, price was no object and he only laid down one proviso: The bike had to have a single-sided RC45 swingarm. “We had never done that before,” Erion admits. “Initially, I had second thoughts. But that was the only thing he asked for.”

Actually, mating the swingarm to the CBR’s frame was relatively easy. Aside from some minor machine work, the arm bolted right on. Erion even retained the stock suspension linkage and upper shock mount. The only consideration, he says, was chain alignment. “We had to space the

countershaft sprocket outboard to align the chain with the rear sprocket.” Wheelbase is nearly the same as stock. “The distance from the swingarm pivot to the rear axle is virtually identical,” Erion says.

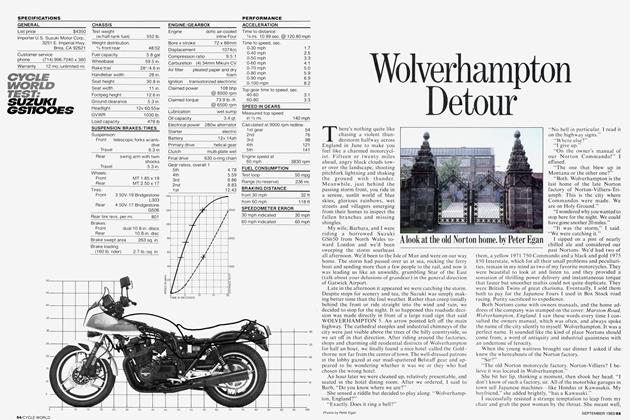

While the twin-spar aluminum frame is unchanged save for black powdercoating, the rest of the chassis is completely revised. In fact, nothing is stock.

Erion equipped the bike with ultra-trick Öhlins racing suspension. Armed with more knobs than a Sony Trinitron, the upside-down fork uses handmade triple-clamps, stout 45mm tubes, external spring-preload adjusters, and independently adjustable compression and rebound damping. The rear shock is equally variable, having provisions for compression and rebound damping, preload and ride height.

Other significant-and equally expensive-additions include 17-inch HRC racing wheels in 3.75and 6.25-inch widths and enormous, six-pot Wilwood brakes. “I wanted something in a lightweight, racing-style brake,” Erion says. “Plus, they’re made in America.” Because the GP-style Brembo master cylinder eliminates the stock brakelight switch, an inline pressure sensor triggers the taillight.

Motor man Dan Kyle built the engine, settling on a relatively mild (by his standards) state of tune that would yield a broad, easy-to-use powerband-a trait Enrile, who lives in the Philippines and has yet to see the bike, will surely appreciate.

Despite Kyle’s conservatism, the engine has its share of exotic parts. The crankshaft and engine cases are stock, but titanium Pankl connecting rods and cylinders bored to accept lmm-oversize HRC pistons (raising displacement from 893cc to 919cc) hint at racebike performance. “We tend to stay away from really big-bore stuff,” Kyle says. “The pistons weigh too much and reliability suffers.”

Erion’s customergrind camshafts, wilder than stock but milder than those used on the team’s championship-winning, 170-horsepower racebikes, open stock valves. The cylinder head received standard customer treatment. “We have certain flow numbers that we know work,” Kyle says cryptically.

Upstream, a bank of 39mm Keihin-FCR flat-slides replaces the stock 38mm Keihin CVs. “We’ve tried 41s, but the 39s produce more midrange power,” Erion says. “We’ve yet to see a big gain with 41s.” Fresh air is funneled through a molded intake scoop and into a carbon-fiber airbox. “This is the first streetbike we’ve built that uses an airbox,” Erion confesses.

The mechanical exotica doesn’t end there. The oneway, slipper-type clutch and close-ratio, six-speed transmission are limited-production HRC parts. Together, they retail for an eye-watering $5200-more than half the cost of a new ’96 CBR900RR. And they perform beautifully, thank you very much.

If that’s not enough to get your salivary glands, well, sali-

vating, this will: Spent exhaust gasses exit through a titanium 4-into-l that snakes up behind the swingarm pivot, splitting into two pipes and culminating in an innovative, automotive-style muffler built by John Van Dyke. CNC-

machined endcaps protrude from tapered openings in the one-piece tailsection, a la Ducati 916.

Modeled after the team’s race ’glass but with superior attention to detail, the hand-formed bodywork-expertly carved-out to accept Japanese domestic-market CBR250RR dual headlights-was beautifully executed by Don Ewart. The edges are silky smooth, fitment exact. Asked to liberate the bike of its fairing and tailpiece so photographer Jeff Allen could shoot detail photos, Erion whipped off the Dzus-fastened panels in a flash. The

5-gallon aluminum fuel tank, secured like most else on the bike with titanium from Mansson Technologies-in all, $3600 worth-comes off just as easily. “My intention was to make everything as clean and tidy as possible,” Erion says.

“We spent three days on the wiring harness alone.”

Creature comforts weren't given nearly as much consideration; this is a race-replica, after all. To wit, the aluminum clip-ons are mounted low, below the top clamp. And the scat is a scrap of Corbin naugahyde glued to foam so thin that the mounting hardware gouges your backside.

Even so, the bike is one hell of a ride.

On the street, acceleration is brutal (060 comes in 2.7 seconds, the quartermile in 10.2 at a blistering 142 mph).

First gear is good for more than 90 mph.

Steering is right now immediate. The brakes are light years beyond even your wildest imagination. The suspension soaks up imperfections in the pavement with near-magical proficiency. Quite frankly, the Erion CBR900RR is almost too good to be true.

Ditto the bike’s racetrack performance. The front fork scoffs at mid-corner ripples. And although Toland detected a bit of excess lever travel in his final timed session at Willow Springs, the Wilwoods otherwise offer beyond-reproach performance. Same for the engine and gearbox. Throttle inputs are rewarded with brain-curdling thrust. The short straight between Turns 8 and 9 simply evaporates. Comer-entrance

speeds are colossal. Just before slamming on the binders for Turn 1, Toland was clocked at 161 mph (a stock CBR900RR went 144 mph during our recent Ultimate Sportbike Challenge). Remarkable.

Still, there are some at-the-limit shortcomings. “I could hold my line, but I couldn’t tighten it, especially in Turns 2

and 8,” says Toland, who races a full-pop Erion CBR in AMA SuperTeams competition. “And we couldn’t drop the front end anymore because the tire was already contacting the lower fairing under braking. It isn’t nervous or anything, but it’s more of a streetbike. The racebike is more precise.” Nonetheless, Toland’s best lap was a very respectable l :25.2, a couple of seconds off the outright track record, and 3.5 seconds quicker than he went on a stocker.

Okay, so how much moola? “The bottom line, excluding the cost of the motorcycle, is $54,000,” Erion says without blinking. “Sure, the HRC parts are expensive-someone has to pay Mick Doohan’s salary,” he quips.

Truth be told, Erion says he didn’t make much money off this bike, and that he charged a reduced rate for labor. “Most of that (total price) is hardware,” he says. “The clutch, the HRC wheels and the Qhlins fork are extraordinarily expensive. Hell, the rear wheel alone costs $2400. Then, to charge for all of the hours spent on the chassis, the body, the exhaust system-it would be unfair.”

Profit margins aside, Erion is absolutely tickled with his creation-and its performance. “The CBR900RR is a racereplica,” Erion says. “We took Honda’s RR and made it an RRR-now it’s a Real Race Replica.”

Won’t Enrile be surprised.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue