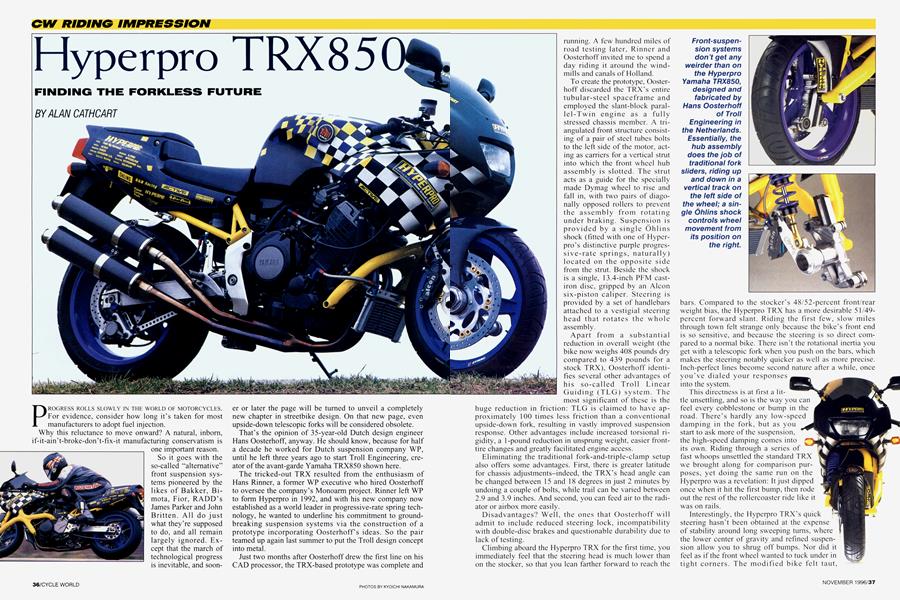

Hyperpro TRX850

CW RIDING IMPRESSION

FINDING THE FORKLESS FUTURE

ALAN CATHCART

PROGRESS ROLLS SLOWLY IN THE WORLD OF MOTORCYCLES. For evidence, consider how long it’s taken for most manufacturers to adopt fuel injection.

Why this reluctance to move onward? A natural, inborn, if-it-ain’t-broke-don't-fix-it manufacturing conservatism is one important reason.

So it goes with the so-called “alternative” front suspension systems pioneered by the likes of Bakker, Bimota, Fior, RADD’s James Parker and John Britten. All do just what they’re supposed to do, and all remain largely ignored. Except that the march of technological progress is inevitable, and sooner or later the page will be turned to unveil a completely new chapter in streetbike design. On that new page, even upside-down telescopic forks will be considered obsolete.

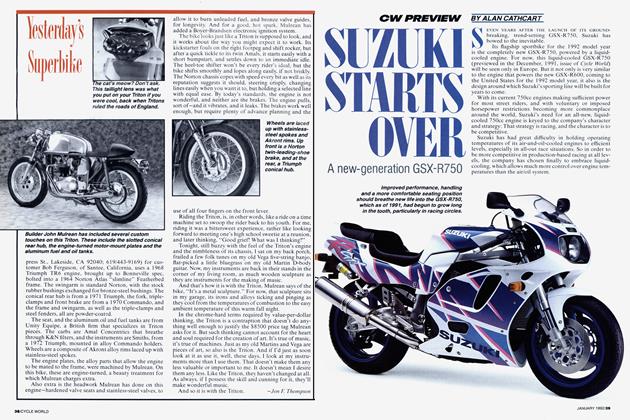

That’s the opinion of 35-year-old Dutch design engineer Hans Oosterhoff, anyway. He should know, because for half a decade he worked for Dutch suspension company WP, until he left three years ago to start Troll Engineering, creator of the avant-garde Yamaha TRX850 shown here.

The tricked-out TRX resulted from the enthusiasm of Hans Rinner, a former WP executive who hired Oosterhoff to oversee the company’s Monoarm project. Rinner left WP to form Hyperpro in 1992, and with his new company now established as a world leader in progressive-rate spring technology, he wanted to underline his commitment to groundbreaking suspension systems via the construction of a prototype incorporating Oosterhoff’s ideas. So the pair teamed up again last summer to put the Troll design concept into metal.

Just two months after Oosterhoff drew the first line on his CAD processor, the TRX-based prototype was complete and running. A few hundred miles of road testing later, Rinner and Oosterhoff invited me to spend a day riding it around the windmills and canals of Holland.

To create the prototype, Oosterhoff discarded the TRX’s entire tubular-steel spaceframe and employed the slant-block parallel-Twin engine as a fully stressed chassis member. A triangulated front structure consisting of a pair of steel tubes bolts to the left side of the motor, acting as carriers for a vertical strut into which the front wheel hub assembly is slotted. The strut acts as a guide for the specially made Dymag wheel to rise and fall in, with two pairs of diagonally opposed rollers to prevent the assembly from rotating under braking. Suspension is provided by a single Öhlins shock (fitted with one of Hyperpro’s distinctive purple progressive-rate springs, naturally) located on the opposite side from the strut. Beside the shock is a single, 13.4-inch PFM eastiron disc, gripped by an Alcon six-piston caliper. Steering is provided by a set of handlebars attached to a vestigial steering head that rotates the whole assembly.

Apart from a substantial reduction in overall weight (the bike now weighs 408 pounds dry compared to 439 pounds for a stock TRX), Oosterhoff identifies several other advantages of his so-called Troll Linear Guiding (TLG) system. The most significant of these is the huge reduction in friction: TLG is claimed to have approximately 100 times less friction than a conventional upside-down fork, resulting in vastly improved suspension response. Other advantages include increased torsional rigidity, a 1-pound reduction in unsprung weight, easier fronttire changes and greatly facilitated engine access.

Eliminating the traditional fork-and-triple-clamp setup also offers some advantages. First, there is greater latitude for chassis adjustments-indeed, the TRX’s head angle can be changed between 15 and 18 degrees in just 2 minutes by undoing a couple of bolts, while trail can be varied between 2.9 and 3.9 inches. And second, you can feed air to the radiator or airbox more easily.

Disadvantages? Well, the ones that Oosterhoff will admit to include reduced steering lock, incompatibility with double-disc brakes and questionable durability due to lack of testing.

Climbing aboard the Hyperpro TRX for the first time, you immediately feel that the steering head is much lower than on the stocker, so that you lean farther forward to reach the bars. Compared to the Stocker’s 48/52-percent front/rear weight bias, the Hyperpro TRX has a more desirable 51/49percent forward slant. Riding the first few, slow miles through town felt strange only because the bike’s front end is so sensitive, and because the steering is so direct compared to a normal bike. There isn't the rotational inertia you get with a telescopic fork when you push on the bars, which makes the steering notably quicker as well as more precise. Inch-perfect lines become second nature after a while, once you’ve dialed your responses into the system.

This directness is at first a little unsettling, and so is the way you can feel every cobblestone or bump in the road. There’s hardly any low-speed damping in the fork, but as you start to ask more of the suspension, the high-speed damping comes into its own. Riding through a series of fast whoops unsettled the standard TRX we brought along for comparison purposes, yet doing the same run on the Hyperpro was a revelation: It just dipped once when it hit the first bump, then rode out the rest of the rollercoaster ride like it was on rails.

Interestingly, the Hyperpro TRX’s quick steering hasn’t been obtained at the expense of stability around long sweeping turns, where the lower center of gravity and refined suspension allow you to shrug off bumps. Nor did it feel as if the front wheel wanted to tuck under in tight corners. The modified bike felt taut, responsive, predictable and refined. It did not feel extreme, loose, heavy-steering or demanding. It was just plain fun to ride.

Worries about braking power proved unfounded, as even a succession of stops from high speed failed to produce any fade. With no fork to deflect, the Troll front end delivers constant geometry and optimum suspension response at all times. This allows you to brake hard into the apex of a turn with all the forces fed back into the chassis instead of the fork bushings.

The fact that a revolutionary bike fresh off the drawing board works this well is truly impressive. Yet the biggest benefit of the Troll system may well be the freedom it allows motorcycle designers. My visit to Hyperpro’s headquarters happened to coincide with an inspection by a designer from one of Europe’s top motorcycle manufacturers. He’d seen the bike at fall’s Milan Show and was interested in forging a collaboration.

After swearing not to reveal his name or that of his company, I found this designer’s expert assessment of the Hyperpro quite fascinating: “I’ve examined every major alternative twowheeled chassis design produced over the last decade, and this

is the only one that incorporates all the benefits the others collectively offer, without any inherent drawback of its own. Oosterhoff s system allows the fundamental restructuring of motorcycle design that we are all waiting to achieve, without sacrificing any dynamic quality.”

Two days after my test ride, the Hyperpro TRX was flown to Japan. It’s still there. Want to guess why? □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue