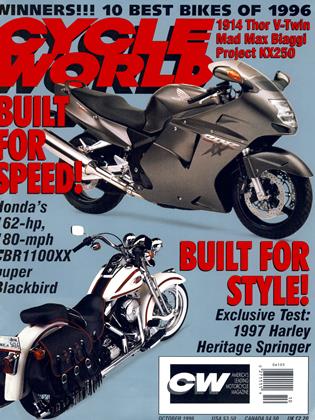

MAD MAX!

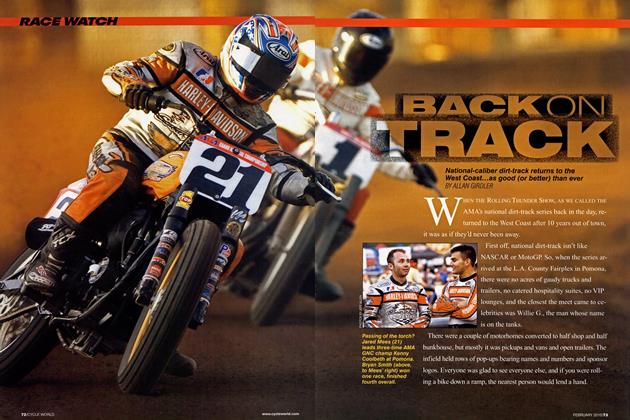

RACE WATCH

An inside look at a complex champion

MICHAEL SCOTT

WHEN A HANDSOME YOUNG ITALIAN DECIDED to forego his beloved soccer one day to ride a 125cc Aprilia around the Vallelunga racetrack, Europe’s most popular sport lost a very remarkable character. In a few short laps, the impressionable and passionate Massimiliano Biaggi, just 17 years old, was instantly hooked on motorcycles.

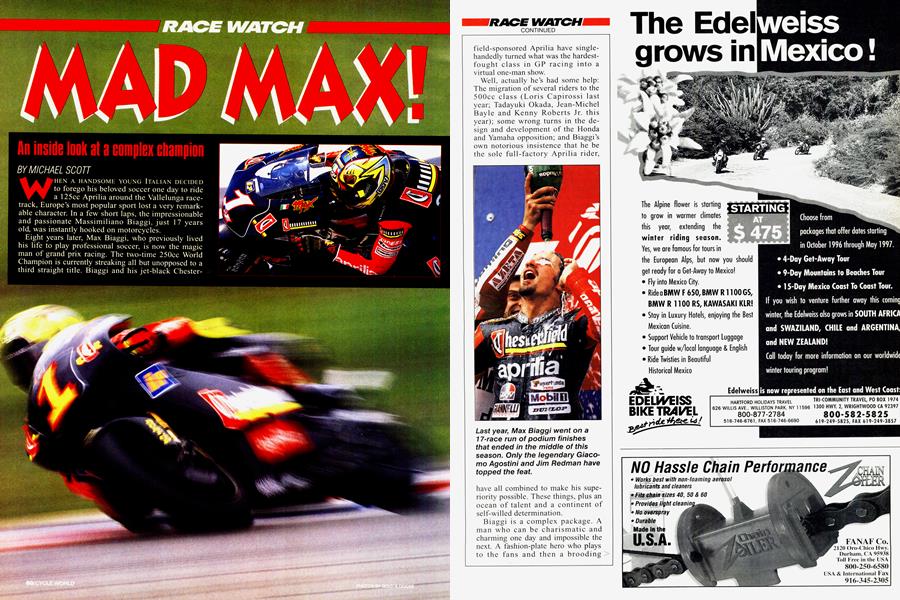

Eight years later, Max Biaggi, who previously lived his life to play professional soccer, is now the magic man of grand prix racing. The two-time 250cc World Champion is currently streaking all but unopposed to a third straight title. Biaggi and his jet-black Chester-] field-sponsored Aprilia have singlehandedly turned what was the hardestfought class in GP racing into a virtual one-man show.

Well, actually he’s had some help: The migration of several riders to the 500cc class (Loris Capirossi last year; Tadayuki Okada, Jean-Michel Bayle and Kenny Roberts Jr. this year); some wrong turns in the design and development of the Honda and Yamaha opposition; and Biaggi's own notorious insistence that he be the sole full-factory Aprilia rider,

have all combined to make his superiority possible. These things, plus an ocean of talent and a continent of self-willed determination.

Biaggi is a complex package. A man who can be charismatic and charming one day and impossible the next. A fashion-plate hero who plays to the fans and then a brooding > recluse who deliberately breeds fear and loathing in his rivals.

The Italian national hero points out the simple desires of his youth: “When I was young, I had a 125 Aprilia, strictly for transportation. I had no interest in motorcycles. I wanted to play for the Rome soccer team. But once I went around a racetrack the first time...! knew racing would be my life.”

Biaggi’s first season was a low-key affair, riding his own Aprilia with the help of his father. Neither knew much about machine preparation. The young rider was fast, but blow-ups and crashes kept him from winning.

In 1990, a professional mechanic offered his help. Max swept to victory in six out of seven outings in the 125 Sport Production series-an Italian series that breeds roadracers in the same way that American dirt-tracking once produced a generation of 500class heroes. Another career-setting milestone was set at Vallelunga when he rode Doriano Romboni’s factory Honda at an Italian 125cc National round and finished third, ahead of World Champion Capirossi. Carlo Pernat, head of Aprilia’s factory team, was quite impressed with the hard-riding newcomer. He promptly signed Biaggi for a factory ride in the 1991 European 250cc Championship. Convincingly, Biaggi won it with one race to go. Here was a man clearly destined for bigger things.

And they came shortly. Pernat assigned Biaggi to Aprilia’s “B-string” GP team the next year, riding along> side Pier Francesco Chili on Telkor sponsored machines. While Biaggi's first win came at the final GP of the season, he made his mark throughout as a fearless rider prepared to risk> everything, with the natural skill to get away with it most of the time. Others contesting the front positions soon learned to give him a wide berth, for he was utterly ruthless on the attack. In Germany, a fairing-bashing, last-lap bid for victory had Italian compatriot Romboni complaining bitterly about Biaggi’s dangerous riding. Grand prix racing’s latest prizefighter responded tersely: “This is motorbike racing, not chamber music.”

It was clear from the start that Biaggi was his own man. The Italian paddock community is a powerful force and something of a perpetual pasta party. His countrymen were at first puzzled and later somewhat offended by this new recruit for whom a place was reserved at the top table-but who didn’t want to join in. Biaggi promptly compounded the surprise by breaking ranks completely. Instead of taking the spot awaiting him on Aprilia’s main factory team for 1993, he instead switched to the Rothmans-sponsored Honda team.

The gambit didn’t work, at least in > racing terms. Biaggi won only a single race on the Erv Kanemoto-tuned NSR250. He grew increasingly withdrawn and morose as the season unfolded and Yamaha-mounted Tetsuya Harada rolled on majestically to take the title. Fourth overall was far short of his and Honda’s expectations.

But Aprilia was thrilled with Biaggi’s misfortune on the rival machine. The factory gave Pernat orders to forgive and forget-to welcome the prodigal son back into the family. And did Biaggi ever repay him. In 1994, with Harada injured early in the season, an invigorated Biaggi fought a year-long battle with Capirossi and Okada to claim his first 250 GP title. It all came down to the last race, where instead of cruising to a safe second to sew up the championship, Biaggi tore it up with a risk-all runaway win that later became his trademark.

It was the same tune in 1995, sung even more convincingly. The previously erratic racer had added consistency to his armory of devastating speed and fearsome determination. He finished all but one of the 13 races on the podium, winning eight of them, and starting a string of 17 consecutive podium finishes.

Biaggi is clearly a complete racer, the man to beat in the 250 class. But his talents range far beyond the track. He shows intelligence, maturity and an extraordinary determination to excel in all facets of his life. He wears the multiple hats of racer, manager, adviser, agent and public-relations flak while at work. Like he does on the track, Biaggi proceeds with skill, flair and a single-mindedness that leaves both opponents and colleagues gasping for air.

Then there is the way he deals with contract negotiations. In the face of considerable criticism from the Italian GP community, he drives the little Aprilia factory to distraction with tough mandates. Leveraging a signon fee reckoned to be at least SI million from Aprilia this year, he is by far the highest paid racer in the 250 class. For 1996, he insisted that Aprilia support no other official works 250cc riders. “It is better with one rider so you can concentrate all resources,” he explains glibly. Aprilia was forced to agree-at a cost of the family feeling it had built up over the years with riders and team personnel. This is ably summed up by erstwhile former teammate Loris Reggiani, who persuaded Aprilia into racing in the first place and was canned outright at the end of last season. Everyone expected that Reggiani would be an essential member of the Aprilia family. “Since Max arrived, there is no Aprilia family,” Reggiani snorts scornfully.

At this time, factory and rider are again head-to-head in negotiations for next year. Biaggi put his Doohan-like demands on the table: an asking fee of around $4 million. “Much more than we can afford,” says Pernat, shaking his head expressively. “Too bad,” replies Biaggi, who’s also courting offers from top-level 500 teams. “I don’t come any cheaper.”

Where does Biaggi find the strength to alienate the very company that has fostered his success, to exasperate fellow racers so completely? How does he do this all by himself?

Pernat knows the mercurial racer better than anyone in the paddock, yet he is frustrated by his star’s tough demands. The team boss has been around Biaggi for five years, but they are not friends. “Max doesn’t have any friends in racing,” says Pernat, “only enemies.” This is something Biaggi gladly confirms while paraphrasing the words of Italian racing legend Giacomo Agostini. “Racing is like war,” Biaggi says. “When I am at the racetrack, it is for business. I think only about racing. My friends and my social life are at home. I never mix my racing and private life.”

Pernat sighs as he digs for deeper reasons why Biaggi is so winningly wonderful and yet so desperately difficult. “Everybody in the world has their make-up shaped by what happens in their life, especially early on,” he says. “When Max was very young, soon after he was born, his mother left the family. Max’s father was not a perfect man. Things were very difficult for Max growing up. He became a loner. And he is a loner for life. Now, he wants to show that he doesn’t need anybody else.”

This explains Biaggi’s motivations off the track, but ask him where he finds his superiority atop the Aprilia and he will smile innocently and give a modest answer. “I don’t know,” he says. “I always try to do my best. I work hard and have a good feeling for my bike.”

In this last statement, he so casually mentions what many in racing see as the double world champion’s key to success. Pernat doesn’t deny this, but first points to competitors’ shortcomings. “There is no challenge this year,” Pernat says. “The Yamaha engine is no good. You could see it in Harada’s face after the first race. Honda made a mistake with its chassis. The engine is good, but not the handling.” On Biaggi’s comfort with his machinery, Pernat says, “Don’t forget that almost all of Max’s racing experience is with the Aprilia. At first, he didn’t change the bike much, he grew into it. In the last couple of years he’s learned a lot and has the ability to set the bike up very well.” “Biaggi’s riding style suits the Aprilia,” observes Wayne Rainey, who manages championship rival Harada. “Basically, the bike’s been built around him. You can see from his riding that he’s totally familiar with everything it’s going to do.”

Now that he has become master of the 250 class, the probable three-time champion is aimed at repeating this domination on a 500. “It is the ambition of any rider,” Biaggi says. “But I will only move into a top-level team with a top-level bike.” For this reason, he isn’t too interested in Aprilia’s 410cc V-Twin lightweight. Without a blink, he says, “Perhaps in the future the bike will be good, but it needs development. That is a job for a rider at the end of his career.” Biaggi has been in discussions with all of the factory 500cc teams. While they’ve been taken aback by his outrageous financial demands, all agree that he is a highly desirable property. But nobody expects him to jump straight onto a factory V-Four and start winning races right away. On the contrary, many say he will find it harder than he thinks. Rainey has a unique perspective as both a rider and team owner. He says, “What I’m seeing with Capirossi (the former 250cc World Champion and his current 500cc rider) as well as with Bayle and Kenny Jr. is how much they still have to learn. They’re doing well, but it’s gonna take two or three years before they reach their peaks.”

Biaggi is under no illusions, but puts a rather shorter timetable on his transition to the Big League. “I have never ridden a 500, not even the Aprilia VTwin,” he says. “But I know it needs a different technique. I can learn that, but will need a full year to do so.” While he wants to jump to 500s as soon as possible, there is pressure from outsiders for him to hang back in 1997. Next year, a national Italian television network will air GPs, replacing the low-penetration pay channel currently doing so. The new rights-holders would love to have Max as a guaranteed superstar, and may even be prepared to help Aprilia pay for the privilege. Could this be enough to tempt him into staying?

No matter which path he decides to take, Massimiliano Biaggi, the boy who once only wanted to play soccer, is well on his way to becoming one of the greatest motorcycle racers the world has ever seen. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue