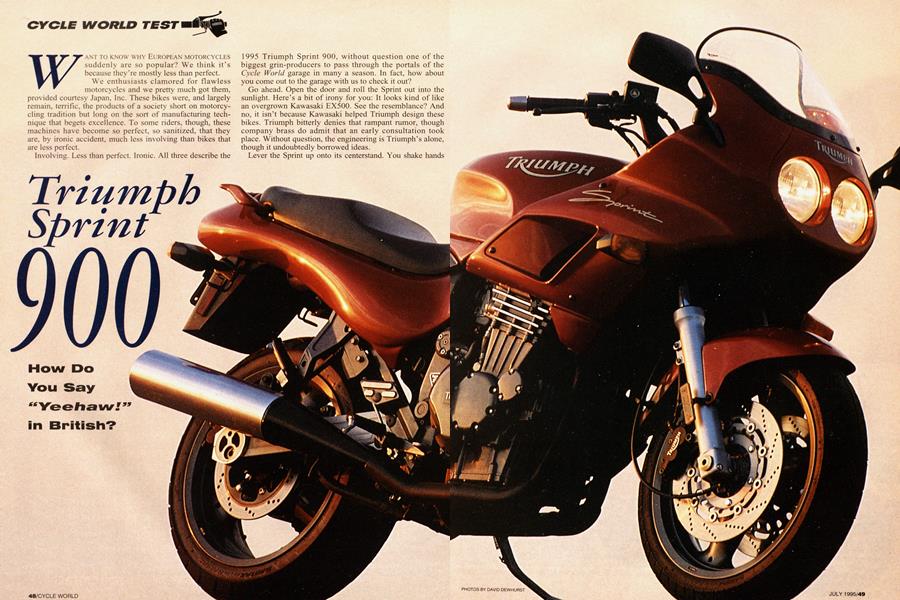

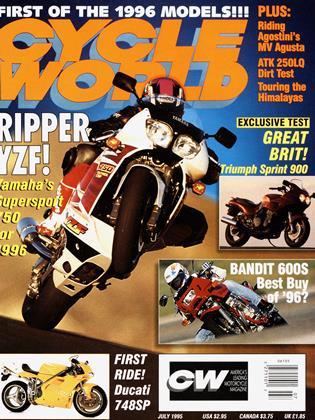

Triumph Sprint 900

CYCLE WORLD TEST

How Do You Say "Yeehawi!" in British?

WANT TO KNOW WHY EUROPEAN MOTORCYCLES suddenly are so popular? We think it’s because they’re mostly less than perfect. We enthusiasts clamored for flawless motorcycles and we pretty much got them, provided courtesy Japan. Inc. These bikes were, and largely remain, terrific, the products of a society short on motorcycling tradition but long on the sort of manufacturing technique that begets excellence. To some riders, though, these machines have become so perfect, so sanitized, that they are. by ironic accident, much less involving than bikes that are less perfect.

Involving. Less than perfect. Ironic. All three describe the

1995 Triumph Sprint 900, without question one of the biggest grin-producers to pass through the portals of the Cycle World garage in many a season. In fact, how about you come out to the garage with us to check it out?

Go ahead. Open the door and roll the Sprint out into the sunlight. Here’s a bit of irony for you: it looks kind of like an overgrown Kawasaki EX500. See the resemblance? And no, it isn’t because Kawasaki helped Triumph design these bikes. Triumph bitterly denies that rampant minor, though company brass do admit that an early consultation took place. Without question, the engineering is Triumph’s alone, though it undoubtedly borrowed ideas.

Lever the Sprint up onto its centerstand. You shake hands with an important element of the Sprint's personali ty: its considerable size. It rolls on a 58.7-inch wheel base, and it weighs 526 pounds with an empty fuel tank. It's a big, rangy

bike, and you've got to contend with that bulk and confront it when you deal with any of these new Triumphs.

Go ahead, climb aboard. See what we mean? The seat's plush and comfortable, if a bit narrow at the front, where it meets the 6.6-gallon fuel tank. You tend to find yourself sitting mostly upright, with a slight forward lean in a comfortable sport-touring position. You also find yourself situated toward the front of the seat because the tank is long and the cast handlebars, which are bolted to the top triple-clamp, are relatively flat. These bars offer one thing to dislike about the Sprint-their angle puts your hands and wrists in a weird position. We'd be more comfortable, and you would be, too, if the bars’ rise was higher, and their ends, where the barend weights are, were angled down lower.

Go ahead, adjust the mirrors. Pretty cool, eh? You easily sec past your elbows to get a really fine rear view, not always something you can take for granted on the current crop of motorcycles. And as you'll see when you start the engine, the mirrors don't vibrate at all, so your rear view stays perfectly clear all the time, even at politically incorrect speeds.

Settle in, feel the controls. Everything fits, everything works. If you don't like the way the clutch and brake levers feel, change them-both are four-way adjustable, a nice touch. So, everything adjusted, go ahead and roll the Sprint off its centerstand. Whoa! It's a long way to the ground, eh? The Sprint is a tall bike, made that way by the combination of the tall Triumph engine and a frame that uses a spine that must run over the top of the engine, further increasing the bike's verticality. What's interesting, though, is that Triumph designed the engine to be very rigid, and used triangulated bracing to harness it as a stressed member. So, as you'll see, no matter how hard you ride it, the Trident feels very solid. Solid, even, in spite of the way the bodywork on this testbike fits. On the left side, the top of the fairing fits very snugly up against the bottom of the fuel tank. But on the right, there's a gap of up to a half-inch. It's a manufacturing glitch there's no excuse for. We suspect that simply bending some of the mounting tabs might close the gap.

Okay: Jacket, gloves and helmet on, and key on, too. Move the choke lever to fullrich, thumb the button-yes. the switchgear feels Japanese because it is Japanese-the 885cc Triple roars into life with a surprising lack of vibration, and with a sound quite unlike the turbine-whirr ofthat other current Triple, the one from BMW.

This one has a coarser feci and a Siren'scall quality to its exhaust note, even though it is equally smooth. A Triple seems to break natural law, just like an inline-Five does. Plenty of people have found happiness with Fives-Audi, Mercedes-Benz and Volvo, among them. And that's what this engine kind of sounds like, with more combustion impulses than a Twin, but with fewer than a Four. Like the automotive Fives, this Triple is counterbalanced, so it is very smooth. Yes, you can feel it down there, but only to the point where you know it's up and running. At no point do vibrations intrude to the degree that fingers and toes tingle.

As you pull the clutch lever in and select first gear, you find other important truths about this Triumph design: company engineers obviously spent a lot of time making sure things were just right. For instance, clutch pull is light enough to be easily handled by two fingers, and shifting action is equally light and very positive. Also, as you engage the clutch, the feel is meaty and smooth, as though it was designed to handle double the Sprint’s 88 rear-wheel horsepower. And the engine is so torquey right off idle that you've got to work at it to stall, in spite of relatively high overall gearing.

Rolling, you click up through the gears feeling how short the shifting throws are. If you’re not firm enough on your downshifts, you'll encounter an occasional false-neutral between fourth and third gears, at least on this testbike. It’s not something we could duplicate when we tried to, it just happened at the odd moment.

Move the bike around as you get used to it and you find that its feel and handling are slow to the point of being deliberate, for several reasons. First, there’s the Sprint’s size, its weight and length, and the fact that it carries 6.6 gallons of fuel-that's about 46 pounds-up high. Second, there’s its steering geometry, shared by the other bikes in the Triumph line: 27 degrees of rake with 4.1 inches of trail. All these factors conspire to make the Sprint a machine with superlative directional stability. That very stability, however, means that it is somewhat more reluctant to flick side-to-sidc than something with more aggressive geometry. A Honda CBR900RR, for instance, is a lot more compact than the Sprint, a bit more nervous at speed and changes directions almost before you think about it. It’s geometry is 24 degrees of rake and 3.5 inches of trail. A different motorcycle for a different purpose, never mind that it also displaces just 8 more cubic centimeters.

But if the Honda looks like a race-replica, the Sprint doesn’t. It looks like the soul of discretion. Rest assured, it ain't. Just twist the throttle and sec. It's an unalloyed hooligan. a kind of highway anarchist wearing sensible clothes. Breathing through a trio of 36mm Mikunis and using the same “green” cams as the Trident, Trophy, Daytona 900 and Speed Triple-thc Tiger and mellowed-out Thunderbird get the softer “blue” cams and the Super 111 and Daytona 1200 get the high-lift “red” cams-the Sprint's engine will pull from 2000 rpm, but begins rasping out really usable horsepower at 4000 rpm, with the power building all the way past the 9500-rpm redlinc to about 10,300, where the electronic rev limiter shuts off spark. And there’s a bit of a power step at about 7500 rpm, just to make things interesting.

Notice as you ride the Sprint the same thing we see with so many other bikes-the quality of the power it produces is every bit as important as the quantity of power. The quality of the Sprint’s power is such that is instantly available anywhere in the rev range and easily modulated between mellow acceleration, if that’s what you crave, and shot-out-of-a-cannon acceleration, if that’s what’s on your mind. That this same engine feels even more urgent in the Speed Triple, with its power steps in different places, is as much a matter of perception as anything else, according to engineers at the Triumph factory. That bike uses five speeds instead of the Sprint’s six, and its ergonomics, thanks to its low clip-on bars and lack of a fairing, give it a different attitude, and hence a very different feci.

Tuned this way, the Sprint’s engine delivers maximum urge between 7500 rpm and 10,000 rpm, and because it has relatively little flywheel effect and relatively high 10.6:1 compression, it has good engine braking. So try this: Ride at a relaxed but quick pace just using the throttle. Roll out, you slow down; roll into it, you speed up. The Ducati eightvalve V-Twins work much this same way, and arc fun to ride for some of the same reasons. Instead of a huge hit of power way up high in the rev range, there's usable power everywhere. Whether you’re doing mellow, throttle-only riding or full gas-and-brake comer-strafing, third and fourth gears are the most useful-third tops out at an indicated 100 mph, and fourth tops at 120, after all, and in each of those gears, this green-cam engine will pull strongly from well below the legal limit. So as you'll see, it’s hard to find yourself in a gear that’s really, really wrong.

As you continue your ride, you’ll find that the Sprint’s suspension isn’t as well-sorted as its engine is. Notice, for instance, the choppiness you feel as you pass over freeway expansion joints-the sort of environment where a sport-touring generalist like this should excel. Honda’s bikes, even the sportiest of them, are plush in such situations because their suspensions are tuned with just a bit of initial softness. It's a lesson Triumph could learn. Also, compression damping on the non-adjustable fork is a bit too firm, and rebound damping a bit too soft. Yet hard braking can bottom the fork, especially over bumps. Things are better at the rear, which is controlled by a gas-pressure shock that offers remote preload adjustment and adjustable rebound damping.

The Sprint likes to be ridden hard, and as you see when you do that, these suspension glitches fade in importance. No matter how you ride, hard or easy, you find that the steering is surprisingly light and neutral. Want to change directions? Just give a bit of a nudge on the handlebar, and the Sprint leans into the classic, sweeping cornering arcs where it excels. And as you feel the Sprint out, here’s what happens: You’re finding yourself at wild lean angles, traveling at outrageous rates of speed. You're thinking, “I can’t believe I'm doing this, and I sure as hell can’t believe I’m doing it aboard a Triumph.” But you are. And you are. This Sprint is just that kind of bike, an eager playmate that reminds us why we love motorcycles.

Stopping? Stopping's good aboard the Sprint, but it could be better. This is, after all. a substantial lump of motorcycle, and though the twin, four-piston Nissin calipers and 12.2inch rotors do their jobs consistently and controllably, we'd like a bit firmer feel at the brake lever, please, and a bit less lever travel during hard stops.

Perhaps the most interesting lesson to be gained from this hypothetical ride aboard the Sprint is how integrated the bike feels, with each system complementing the others, instead of feeling like it was designed in a vacuum by a disparate committee. The Sprint feels composed the way a great German car feels composed. But it was designed and built by Britishers. It doesn’t push any new design boundaries, but it extracts the maximum from the designs it uses.

And if it looks just a little like a big EX500, that’s okay; it’s a delicious irony, even. The EX500 is one of Cycle World's all-time favorite motorcycles, in large measure because it is a simple, unpretentious machine that begs to be ridden. The Sprint is much the same: simple, unpretentious, fast, not perfect, but a lot of fun to ride. And at the same price as the much less well-equipped Thunderbird (which has no centerstand, no adjustable shock, a smaller fuel tank and the softer, blue-cam engine), it's got to be one of the best buys in the Triumph lineup.

Its also a wonderful piece of evidence for motorcycling in general. The industry is alive and well. That Triumph has returned so strongly, with bikes as good as this one, is ample proof of that. E3

TRIUMPH

SPRINT 900

$9995

EDITORS' NOTES

WHEN I PERFORM CERTAIN FUNCTIONS with my computer’s mouse, the computer, which I have hot-rodded into full multimedia form, will repeat back to me with great emphasis, in Peter Lorre's nasal, whining voice, “Oh, Master, I like this one!” Precisely what 1 find myself thinking w hen l ride the Sprint.

This thing is an absolute hoot, and 1 do like it. Maybe too much. I've already got a couple of motorcycles, and 1 don't really need any more of them. 1 also can’t really afford enthusiasms on the scale adding a Sprint to the stable suggests. But 1 can't not afford them, either. It’s a use-it-or-lose-it kind of deal. I went out for a short ride to see what the Sprint was like. I was gone all day. Sure, the Sprint has some maddening little lapses, but it's also one of the most enthusiastic riding partners I’ve found lately. It’s been a while since a motorcycle has so comprehensively returned me to motorcycling’s basics. Yep. I like this one.

—Jon F. Thompson, Senior Editor

No QUESTION, TIlE SPRINT 900 IS A TER rific motorcycle. It's blessed with the same smooth, powerful engine and vis ceral exhaust note that we've come to expect-and admire-from a modern, three-cylinder Triumph. Kudos also to the comfortable riding position, respon sive handling and available integrated hard luggage. Minuses? Excessive front-brake lever travel, wonky suspen sion damping and (for riders over 6 feet tall) a turbulent cockpit at highway speeds.

Now the big question: Would I spend $10,000 for one? Absolutely not. For $1300 less. I’d buy a 1995 Honda VFR750F, which, in my mind, is the finest real-world motorcycle on the market. It, too, has a charismatic engine, comfy ergonomics and a top-shelf finish. It also makes more power, weighs less, has a splendid aluminum chassis with a slick, single-sided swingarm and suspension compliancy second to none. Top that, Triumph. -Matthew Miles, Managing Editor

I'VE DONE MY SHARE OF CARPING IN THE past few years about the lack of truly modern sport-standards. Well, guess what? They’re here.

Yamaha's Seca II qualifies, as does Kawasaki’s Ninja 500. Ditto for Big K’s impressive new GPzllOO. Check out the new Suzuki Bandit 600 in this issue-can the 1200 version be far behind? All have sporting (but not excruciating) seating positions, all have some wind protection (but not so much as to totally hide the motor), all will provide 90 percent of riders as much backroad prowess as they can handle (w'hile serving equally well as competent sport-tourers). Simply put, these neo-standards are all the motorcycle most of us really need.

Add to that list-somewhere near the top-Triumph’s Sprint 900. It’s so good, I’ve ordered one up as part of the CfV long-term fleet. Purely as a service to you the reader, you understand. I’ll get back to you in 10,000 miles or so. -David Edwards, Editor-in-Chief

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontLetter To Willie G., No.2

July 1995 By David Edwards -

Leaning

LeaningNorton Goes To Florida

July 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCHeated Exchange

July 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupIndians, Yes, But Which Tribe?

July 1995 By Ion F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupNaked Honda Gets A Bikini

July 1995 By Yasushi Ichikawa