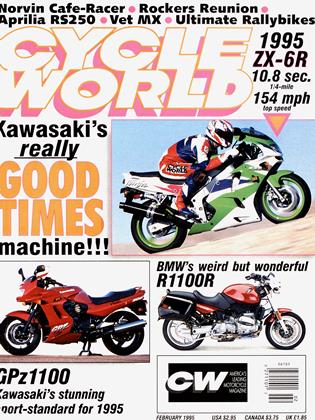

1995 KAWASAKI GPz1100

CYCLE WORLD TEST

A RATIONAL SPORTBIKE FOR REAL-WORLD APPETITES

HUNGRY FOR POWER, COMFORT, STYLE AND versatility at a reasonable price? Here's a recipe that ought to satisfy your appetite: Retune one Kavasaki ZX-11 engine for a bit less of a top-end rush and a tad more midrange grunt; mount it in a double-cradle steel frame that's rigid and robust; fit it with modern suspension absent of costly adjusting devices; design bodywork that provides good weather-protection yet allows a clear view of the engine; add a comfortable, reasonable riding position; mix well and serve to the bomber-jacket-and-jeans crowd, a public that Kawasaki hopes is eager for a rapid, non-intimidating, all-around sport motorcycle that doesn't cost an arm and a leg.

That describes the new-for-’95 GPzl 100, a bike that’s a bit of a gamble on Kawasaki’s part. American motorcyclists have been unreceptive to the industry’s attempts in recent years to build new-age standards, rational machines that hark back to an earlier time when motorcycles were simpler, less specialized, more versatile. Kawasaki, Suzuki and Honda all answered the call and produced such machines (witness the ZR1100, GSX1 100G and CB1000), but not one of them was commercially successful.

Now Kawasaki is trying it again, but with a different twist. This time, the goal is to produce a bike that benefits from race-replica technology without making its rider a slave to it; a bike that communicates the sportbike image so popular these days, but without the compromises that usually accompany it.

According to Kawasaki, the GPz’s engine is essentially the same as the one that has made the ZX-1 1 the world’s fastest production bike. But that’s a tricky word, “essentially." The ZX, you see. gets its phenomenal performance from a number of interlocking bits of tech, the most important of which are its camshafts, carburetors and downdraft head design.

On the GPz, however, all that's changed. Its cams are milder, its carbs are smaller (a quartet of 36mm Keihins, instead of the 1 1 's quad 40s), and the head is more of a sidedraft design. This means the intake tracts force the air-fuel mixture to take a downward turn instead of shooting it straight into the combustion chambers as on the ZX-1 1. Kawasaki says those chambers are identical to the ZX’s, though, as are the 1052cc displacement and 11:1 compression ratio. This dohe, 16-valve engine also uses the same valve sizes that allow the ZX to breathe so freely. The pistons, rings and rods also were lifted straight from the ZX-1 1 parts bin.

Cradling this engine of celebrated ancestry is a singlepiece, double-cradle frame that hangs the motor in two solid mounts and a third that interposes rubber between engine and frame. This rubberized mount, along with a gear-driven counterbalancer, is aimed at reducing the hand-, seatand foot-tingling vibration inherent in inline-Fours.

Output is through a six-speed transmission that incorporates Kawasaki’s exclusive positive neutral finder, and power flows to the rear wheel via an O-ring chain. The swingarm is steel and uses screw-type chain adjusters instead of the eccentric type on the ZX-1 l's aluminum arm, and it pivots on a combination of needle and ball bearings.

Kawasaki is targeting this bike at riders 30 years of age and older, with incomes of $40,000-plus; and the company apparently thinks riders from this group are less critical, less fiddly and less interested in extracting from the bike its final, last ounce of performance. So, while hard-core sportbikes usually have provisions for adjusting virtually every aspect of front and rear suspension, the GPz’s fork and shock are pretty basic. Up front, a conventional, nonadjustable, 4lmm fork works through conservative steering geometry-27 degrees of rake, 4.3 inches of trail. A single Kayaba shock-four-way-adjustable for both spring preload and rebound damping-handles suspension duties at the rear via a typical linkage system.

Wheels are three-spoke alloys with a 120/60ZR17 tire mounted on a 3.5-inch-wide rim up front, and a 170/60ZR17 hoop on a 5-inch-wide rim at the rear. The front brakes are in keeping with the GPz’s rational-performance mission: l l.8-inch rotors up front gripped by two-piston floating calipers, and a single, 9.8-inch rotor pinching a single-piston floating caliper at the rear.

Kawasaki's designers have clad the GPz in bodywork that helps it succeed as a versatile, practical all-arounder. The fairing is a full-coverage item with a windscreen that sticks up far enough to keep windblast off the rider's chest. But the fairing does not wrap as far around the sides of the bike as is the case with many other sport machines, allowing the engine to be much more visible. The designers also have imbued the GPz with many nice detail touches, such as beautifully cast passenger pegs; a passenger grabrail; a large, under-seat storage area; a complete, easy-to-read dash with a digital clock; and a general level of finish that is very high, indeed.

So, in some ways, this is a very modern motorcycle. In others, however, it's a bit of a yesterbike, a ride plucked from motorcycling’s recent past that Kawasaki hopes will point the way to the future. Its stepped seat and slight forward lean, for example, would have been considered very racy a decade ago when Kawasaki’s 1984 GPz900—the very first to wear the now-fabled Ninja name-was a cutting-edge sportbike. But today, in a market accustomed to the GP crouch demanded by hard-edged sport machinery, the GPz's ergonomics seem very relaxed and only mildly sporting.

Riders who yearn for the upright riding position of a standard motorcycle, however, probably will find that grasping the GPz’s stubby handlebars requires too much of a forward lean. Conversely, those stepping back from more aggressive sporting equipment will relish the GPz’s relative upright comfort. They’ll also like the seat, which offers good support and exemplary comfort for both rider and passenger, even over long rides. The moderately rearset footpegs may prove too restrictive for standard-lovers, but sportbike escapees likely will relish the added comfort they provide.

Both ends of the GPz provide a well-modulated ride that's firm but never harsh.

The fork, of course, is not adjustable; but despite having only four distinct adjustment settings for preload and damping, the shock can provide a fairly wide range of rear-suspension behavior. Cranking both adjusters to their lowest settings gives the rear a plush ride, while turning them to their maximums could be the hot setup when the GPz is carrying two large people who have stuffed a weekends’ worth of gear into the optional hard saddlebags.

As far as its handling is concerned, the CiPz is not quite as razor-sharp as most race-replica sportbikes. Kawasaki never intended this machine for production-class roadracing, preferring instead to make it more stable, predictable and user-friendly for all-around sport riding. Thus, its steering is, as its geometry figures suggest, relatively slow compared to that of most full-on sportbikes.

But while that geometry helps give the bike rock-solid stability in a straight line, the GPz is an extremely capable backroad burner anyway. It flicks into corners easily, and once there, is nicely neutral. It requires no pressure on either grip to maintain its pilot's chosen lean angle and corner arc, and it’s willing to change lines with just a moderate push on the handlebar.

Neither was the engine designed to put the GPz on the front row of a starting grid. It doesn’t offer the explosive top-end rush of, say, the ZX-1 1, but what else on two-or four-wheels does? Still, the GPz is extremely powerful by any measure, and offers overall performance on par with a number of pure sportbikes in the big-bore class: 10.85 in the quarter-mile at 128.02 mph, and 158-mph top speed. And in top-gear roll-on acceleration—one of the more useful measures of real-world engine performance—the GPz is just a tenth of a second slower than a ZX-1 1 from 60 to 80 mph, and a tenth quicker from 40 to 60. Not at all shabby for a socalled “compromise” sportbike, eh?

All of this occurs without much fuss or drama, which makes the GPz’s performance rather deceptive. Anywhere above about 3500 rpm, the power is smooth and seamless, with no perceptible lumps or dips in the powerband, no sudden rushes of acceleration. The engine reaches its peak torque at 7000 rpm, but comes within P/2 percent ofthat peak way down at 4500 rpm; and between 4500 and 8500 rpm, the torque doesn’t vary by more than 3 percent. In other words, it has a torque curve as flat as a tabletop. No wonder the power is so useful and accessible.

If there’s any downside to the engine’s performance profile, it's vibration. In the lower rpm ranges, the engine is at least as smooth as most other inline-fours; but starting at around 4500 rpm-which translates to road speeds just shy of 80 mph in top gear—the GPz tingles lightly through the footpegs, despite its counterbalancer and rubber engine mount. As rpm increases, so does the vibration, eventually buzzing the handgrips and mirrors, and intensifying through the footpegs. But unless you cruise for hours on end at 120 or 130 mph, the vibration never reaches a debilitating level.

What all of this means is that Kawasaki truly is rolling the dice with the GPzl 100. The company is betting that for a certain class of rider, typical Open-class sportbikes are too much-too demanding, too intimidating, too uncompromising. too expensive. The GPz is targeted to hit that audience right between the eyes by offering knockout performance, handling and style, but with reasonable versatility. comfort and cost.

If you’re one of those riders, the GPzl 100 may be the feast you’ve been craving.

EDITORS' NOTES

THE ONLY NEGATIVE THING ABOUT THE GPzllOO is that Kawasaki has drawn comparisons between the bike’s engine and that of the ZX-11. It’s like saying the guitarist in your blues band plays like Stevie Ray Vaughan.

So, hard-cores who ride a new GPz may be disappointed to find the engine is not the stuff of which legends are made, but this baby ain’t slow. There’s enough motor for all but the most power-crazed zealots, and it’s smooth, tractable power at that.

The concept behind the engine parallels the rest of the motorcycle: While no one facet boggles the mind, it all works nicely. Fancy a freeway ride? There’s a comfortable riding position and a bump-eating suspension. And optional saddlebags give the GPz cross-country capabilities. Craving corners? Sure, this machine weighs over 500 pounds, but it can hustle and is stable at peg-dragging lean angles.

So, while there’s no one area where the reasonably priced GPz rules, few bikes can hit all the notes as well.

-Robert Hough, News Editor

THIS GPZ THINGIE OUGHT TO BE RIGHT up my alley. After all, I am-or at least, ought to be-long-since past the point of suffering from the ravages of testosterone poisoning. You know the main symptom: an irrational, unreasonable need for speed.

Or, maybe not. I really, really like horsepower, and the GPz doesn’t have a big enough supply of that commodity, not for me. When I whack a throttle grip, I want something to happenl Right now! That’s one of the main reasons I think the GPz’s sistership, the ZX-11, is one of the best motorcycles on the planet. It’s comfortable, and it provides eye-watering forward thrust. Maybe if Kawasaki could just rethink things and somehow give the GPz a bit more of the ZX-1 l’s horsepower. As things are now, I’d spend the extra $2000 bucks for the real thing.

-Jon F. Thompson, Senior Editor

MUCH LIKE YAMAHA’S DISCONTINUEDand sorely missed-FJ 1200, Kawasaki’s latest Open-classer is wonderfully competent and well-rounded. It allows its rider to enjoy the best of both worlds, offering most of the performance and character of a hard-edged sportbike, blended with some of the versatility and comfort of a standard. As a result, the trip to and from the twisties is just as enjoyable on the GPz as the ride through the twisties-even if your favorite backroads are a couple of hours from home.

The GPz 1100 has enough horsepower to accelerate on par with dead-serious sportbikes like Honda’s CBR900RR and Suzuki’s GSX-R1100. Sure, the GPz makes less peak power than a ZX-11 (what doesn’t?) and only goes 158 mph. Big deal. In any real-world context, the GPz is almost as fast; and it has better ergonomics, weighs less and handles at least as well. All for two grand less. Where do I sign? -Matthew Miles, Managing Editor

KAWASAKI

GPz1100

$7999

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontDoctor's Orders

February 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsInvasion of the Midwestern Road Tester

February 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCWeather

February 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's Tasty Trio For 1996

February 1995 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupBmw Scraps Its Triples

February 1995 By Robert Hough