KAWASAKI GPz305

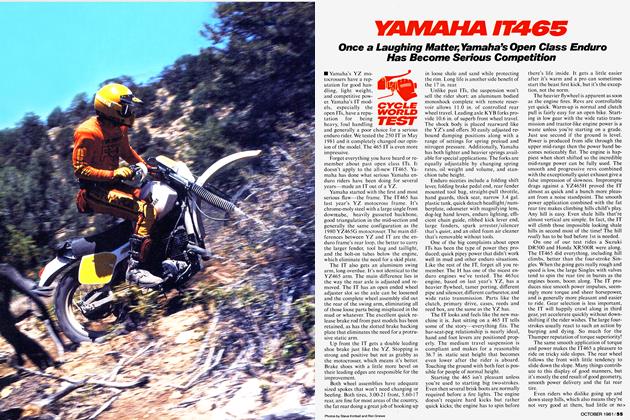

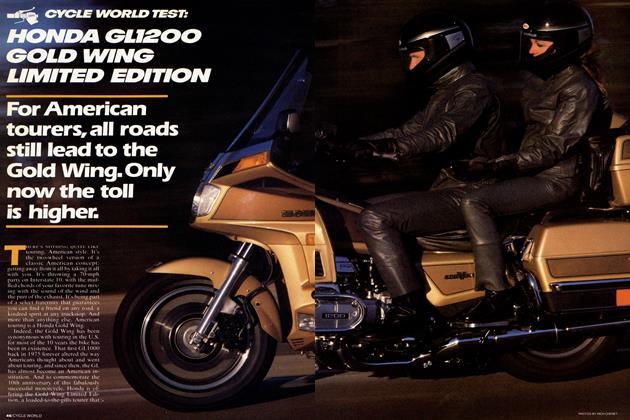

CYCLE WORLD TEST

REBIRTH OF THE SPORTING LIGHTWEIGHT

Brilliant red, racer styled with handlebar-mounted cafe fairing; integrated, swoopy tank/seat/tailsection lines; black-painted engine; black chrome exhaust system; cast aluminum alloy wheels; single rear shock.

If that sounds familiar, it is: this is a look we've seen before.

What's new is that we're talking about the GPz305, a re-do of w hat we knew as the KZ305 CSR cruiser last year. The change is dramatic.

And effective. The GPz305 looks just like its larger brother, the GPz550. so much so that one of our riders, at an east coast club racei with his GPz550. was » alarmed to see a swarm of GPz Kawasakis head into the first turn while he sat in the pits, drinking lemonade.

The panic-stricken rider was tugging on helmet and gloves when a race official happened by, heard what the rush was, and pointed out that the red mass streaming around the racetrack was composed not of GPz550s, but GPz305s.

There's more to the GPz305 than looks. It's easy to be seduced by horsepower, the rush of acceleration from running an 1100 to its redline or reveling in the lazy, no-shifting riding style a big engine allows. Because those aspects of big horsepower machines are so likeable, it's easy to make excuses about the other characteristics that go with big engines: big weight, long wheelbases, and general slow-speed clumsiness. When a big bike like a Honda Interceptor comes along and steers more lightly and feels less ponderous than its direct competition, riders go wild over it. But anybody who hops off an Interceptor onto a GPz305 realizes that the improvement is only relative. There are things little bikes do better.

Like handle, either in the sense of darting around traffic or wailing up winding roads. Not that the 305 necessarily goes around corners any faster, but the GPz is effortless to ride quickly. The 305 only weighs twice as much as the rider (342 lb. with half a tank of gas), instead of three or four times as much. So the 305 doesn't have to be muscled or wrestled into responding: just a quick flick, and it turns.

If anything, the lightness and quickness of the Kawasaki's response takes a little adjustment. It is so responsive that the rider must make a conscious effort to be smooth riding it. Sudden rider weight shifts or steering inputs are amplified into jerky bike movements. If the rider is smooth, though, the Kawasaki is smooth.

There's no mystery why the GPz305 feels the way it does. It isn't just light, but also short and narrow. Pipes and stands are well tucked in. so dragging parts isn't a problem. And the 55.2-in. w heelbase isn't even in the same league as the 60-in. w heelbases common to 1100s and bigger 750s. The rake angle is a steep 26.5°. trail 3.7 In. Adding to the 305*s nimbleness is a set of^iarrow. 18-in. diameter w heels and tires. The front rim is 1.85 x 18 with a 90/90-18 Dunlop F8. the rear a 2.15 xT8 with a 110/80-18 Dunlop Kl30.

The suspension, telescopic forks with individual air fittings up front and that single-shock Uni-Trak system in the rear, is competent, although not perfect. On choppy freeway sections the ride is, well, choppy, something perhaps as much a function of wheelbase as of suspension. There aren’t a lot of adjustments available on the suspension components, and the need for one setting to work for a range of riders left the 305 being over-sprung and under-damped. All of which shows up over uneven pavement or in the fastest sweeping turns, the latter in the form of a manageable, slow, rear-end pogo.

The Kawasaki’s front brake is a single disc, bolted directly to the wheel hub without a carrier, using a single-piston hydraulic caliper. The rear brake is an internal expanding drum, mechanically operated. The brakes are excellent, especially the front disc, giving the rider wonderful feedback and lots of stopping power with little lever effort. But remember that narrow front tire, which contributes to the Kawasaki’s light handling? It also limits the GPz305’s stopping power, starting to howl—on the verge of lockup—long before the bike runs out of front brake.

Despite that, the GPz305 stopped from 60 mph in 132 ft., and took 37 ft. to stop from 30 mph. A better front tire could be expected to decrease those distances.

Outstanding is a good way to describe the GPz305’s seating position. It’s amazing that the little 305 has a better relationship between the bars, seat and pegs than the GPz750 and GPzl 100, but it’s true. The seat is nicely shaped—although it could use more padding for long rides—the pegs moderately rearset, the bars raised and angled back just enough to avoid most of the strained-wrist clipon syndrome.

The handlebar-mounted fairing is topped by a small windscreen. The combination does a respectable job of keeping the wind blast out of the rider’s face. Behind the fairing is a neat instrument module, including a 120-mph speedometer (it’s optimistic, 60 mph indicated is actually 54 mph) and 13,000 rpm tach, a fuel gauge and the usual collection of lights and an odometer/tripmeter.

The GPz305’s engine is a basic air-cooled vertical parallel Twin, sohc with two valves per cylinder. The camshaft is driven off the center of the crankshaft by a roller chain, and opens the valves via rocker arms with adjustable screw tappets. The multi-piece, pressed-together crankshaft uses roller bearings and has its two throws positioned 180° apart: that is, when one piston is at the top of its stroke, the other is at the bottom. Primary drive is straight-cut gear off the right end of the crankshaft, direct to the clutch basket. There’s a six-speed transmission and a toothed belt final drive, the final drive sprocket positioned on the end of the transmission countershaft.

Vibration is a problem with 180° vertical Twins. One solution is to use mechanical counterbalancers, but with the GPz305 Kawasaki chose the simpler, lighter method of rubber-mounting the engine. All three mounting points for the horizontally-split crankcases use rubber to absorb vibration.

Bore is 61mm, stroke 52.4mm for an actual displacement of 306cc. Cast, three-ring pistons with low domes produce a c.r. of 9.7:1.

Don’t be misled and think the GPz305’s engine is a simple transplant from the KZ305 CSR. It isn’t. The GPz makes five more horsepower. That extra power comes from several sources. The GPz’s camshaft has more lift and duration, and the engine revs higher; redline is 11,000 rpm. A balance tube between the exhaust head pipes is moved forward, the result of dyno testing. The cylinder head is a new casting with more fins, and the piston domes are higher, raising compression. The ignition is a magneto CDI with electronic advance, mounted on the left end of the crankshaft and fully contained under the alternator cover.

This is an engine that rewards rider effort. It’s stronger than a 305 has a right to be, turning 14.48 sec. and 88.58 mph in the quarter, reaching 98 mph in the half mile. Thanks to the rubber mounts, the engine is extremely smooth, and the power gets noticeably stronger as the rider runs the bike toward its redline. That type of power curve makes small bikes fun to ride, rewarding the rider for rowing the gearbox, making shift after shift to keep the engine in the range of maximum power, especially on curvy roads. Small bikes with the flat power curve that is so charming in a GS1100, for example, are simply boring; some peakiness is a virtue in the 305 because there wouldn’t be enough power to be entertaining without the hump in the dyno curve.

So the 305 makes its best power above 7000 rpm, and the quantity of power it makes up top is at the expense of bottom end power. That isn’t to say that the 305 can’t be ridden sedately below 6000 rpm; just that strong acceleration demands high rpm, and that the GPz305 likes to be revved.

And it needs those revs when it’s cold.

That is, this isn’t a motorcycle that fires instantly, demands no more than 10 sec. choke, and then motors away from a cold start with nary a look over the shoulder. The GPz305 is lean, lean, lean, a condition delivering fantastic fuel mileage (more on that later) and a resistance to run without full choke until completely, thoroughly warmed up.

Any attempt to turn off the carburetor-mounted choke before the engine is nice and warm leads to stalling and an inability to pull away from a stop. When full choke is kept on, the bike idles at an annoying 3000 rpm. Until it’s warm, the 305 also won’t accelerate cleanly between 4000 and 6000 rpm, coughing and bogging for several miles after starting.

The carburetion is lean to meet emissions rules. This doesn’t actually hurt performance where it counts, and a record 79 mpg means efficiency doesn’t suffer either; too lean a mixture will decrease mpg. Federal law makes it illegal for paid mechanics to change the carbs, but the owner can experiment and make some improvements.

Even churning away on the interstate, 5900 rpm at 60 mph indicated, the Kawasaki gets big mileage numbers. That’s a good thing. Because the Kawasaki has a toothed rubber belt for final drive, changing gearing isn’t a matter of trotting down to the local Kawasaki shop and changing sprockets. The belt is also unique to the GPz. It’s longer than the KZ305 CSR’s belt because the GPz has a longer swing arm to make room for the Uni-Trak suspension system.

What the GPz305 offers the rider is GPz looks, GPz performance in a smaller, lighter package. It runs better than a 305 should, handles better than bikes twice its price, is more comfortable than bikes three times its size. It’s fun to ride, flashy and capable, the most exciting of the small street bikes on the road today. 13

GPz305 carburetor fixes

Deplorable scribe the is standard the only carburetion way to deon our test GPz305. It was so lean at low engine speeds that the bike was hard to ride until thoroughly warmed up by ten miles of riding. Even then it tended to stumble when accelerating from low engine speeds.

We’ve encountered this condition on a few other motorcycles, most recently on pre-1983 Suzuki GS450s and 550s. In all these cases, the low speed leanness comes from jetting that satisfies the ERA, not the motorcycle owner. Fortunately, the owner can make changes that will allow the engine to carbúrete smoothly.

On the GPz, two changes are required. The first is to raise the carb needles relative to the slides. We spaced the needles in our test bike up 0.032 in. using steel number 6 washers from the local hardware store. Each needle is held in its slide loosely (this prevents it from binding on the needle jet and interfering with slide movement) by a plastic spacer located by a retaining ring. To keep the loose fit, the plastic spacer has to be shortened by the thickness of the washer added. Jä^000> We did this by measuring the spacer and washer, and sand-#^ ing the spacer until slightly I

more than .030 in. material was removed. If you lack precision measuring tools, the alternative is to sand the spacer a little, try the fit, and repeat the process until the spacer, washer, and needle fit into the slide without the needle being locked into place.

With only the needles raised, we found our GPz carburetion improved, but still deficient, with some engine bogging when the throttle was rolled on at low engine speeds. Richening the idle mixture cured this. Because larger pilot jets aren’t available for these Keihin carbs, the existing pilot jets must be drilled to a larger size. We used a number 80 drill (a tiny .0135 in. diameter, and available at good hardware stores) mounted in a pin vise to enlarge our pilot jets.

After these mods, our test GPz is a much improved motorcycle. Partial choke is required for only a mile or two during warm-up, and the engine responds to the throttle without bogging. We haven’t repeated performance tests, but the 305 feels stronger every place in the rev band. No real fyel economy penalty was paid for these improvements, \ as test loop milage remained with\ in 1 mpg of the unmodified bike.

KAWASAKI

GPz305

$1799

SPECIFICATIONS

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

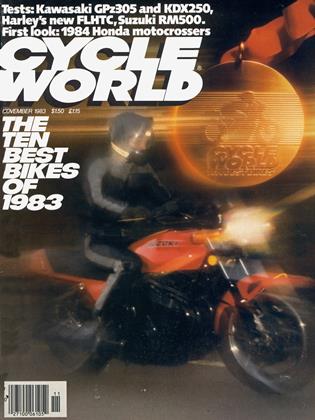

-

Departments

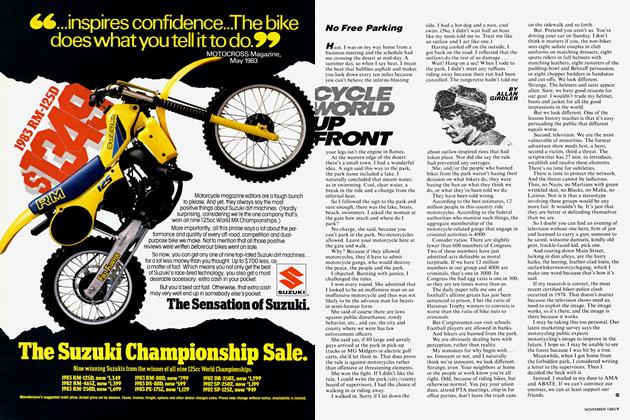

DepartmentsCycle World Up Front

November 1983 By Allan Girdler -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

November 1983 -

Departments

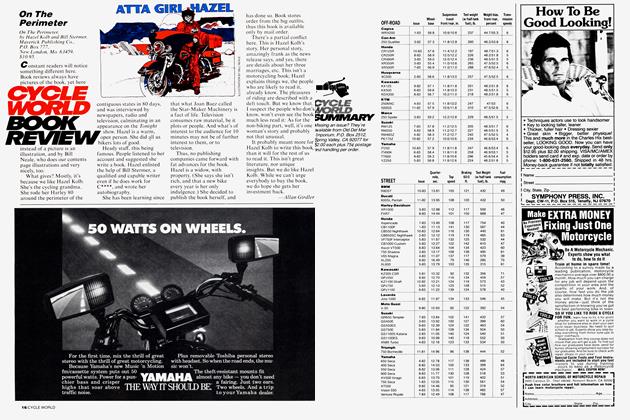

DepartmentsCycle World Book Review

November 1983 By Allan Girdler -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Summary

November 1983 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

November 1983 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

November 1983