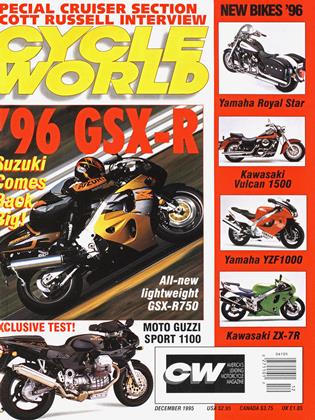

1996 GSX-R750

FIRST LOOK!

SUZUKI GOES BACK TO ITS ROOTS TO REINVENT THE SUPERSPORT 750

KEVIN CAMERON

THE STATELY PROGRESS OF DETAIL IMPROVEMENT MUST, occasionally, be ruthlessly booted forward by bold, wholesale change. You'll never invent the computer by improving a typewriter. Instead of small, safe bets on the familiar, there must come a rash gamble on the farthest extension of knowledge.

Suzuki's original GSX-R of 1985 was such a gamble. It was nearly 100 pounds lighter than its competition, it was more powerful, and it worked. It defined the sportbike as we know it. Since then, GSX-Rs and their like have gained weight as they've gained sophistication. We've all expected Suzuki to reply with a fresh revolution.

The 1996 GSX-R750T is it.

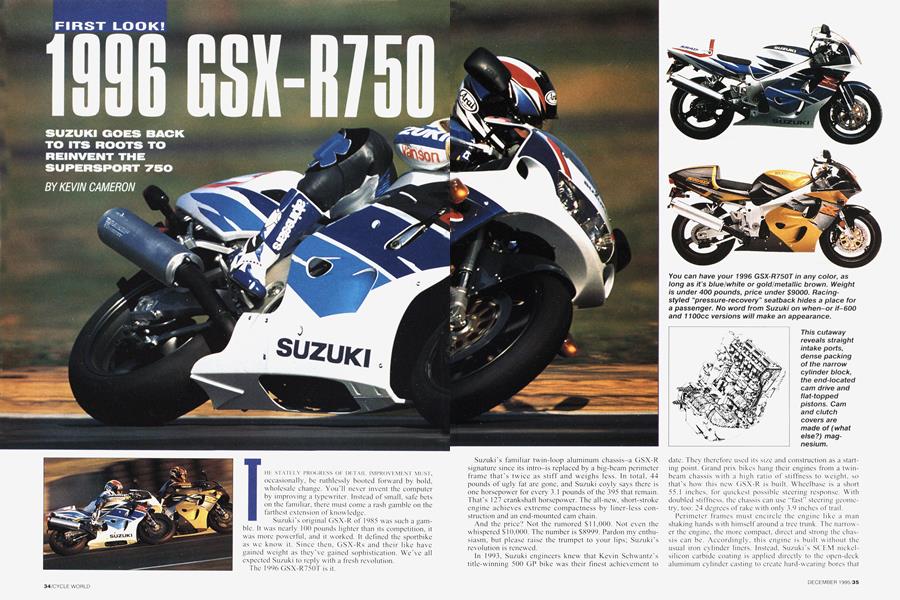

Suzuki's familiar twin-loop aluminum chassis-a GSX-R signature since its intro-is replaced by a big-beam perimeter frame that's twice as stiff and weighs less. In total, 44 pounds of ugly fat are gone, and Suzuki coyly says there is one horsepower for every 3.1 pounds of the 395 that remain. That's 127 crankshaft horsepower. The all-new. short-stroke engine achieves extreme compactness by liner-less construction and an end-mounted cam chain.

And the price? Not the rumored $1 1.000. Not even the whispered $10,000. The number is $8999. Pardon my enthusiasm, but please raise the trumpet to your lips; Suzuki's revolution is renewed.

In 1993. Suzuki engineers knew that Kevin Schwantz's title-winning 500 GP bike was their finest achievement to date. They therefore used its size and construction as a starting point. Grand prix bikes hang their engines from a twinbeam chassis with a high ratio of stiffness to weight, so that's how this new GSX-R is built. Wheelbase is a short 55.1 inches, for quickest possible steering response. With doubled stiffness, the chassis can use “fast" steering geometry. too; 24 degrees of rake with only 3.9 inches of trail.

Perimeter frames must encircle the engine like a man shaking hands with himself around a tree trunk. The narrower the engine, the more compact, direct and strong the chassis can be. Accordingly, this engine is built without the usual iron cylinder liners. Instead, Suzuki's SCEM nickelsilicon carbide coating is applied directly to the open-deck aluminum cylinder casting to create hard-wearing bores that transmit heat better than any liner. The four cylinders Siamese into one rigid unit, with cooling water circulated around it, front and back, from left to right. Cylinder and head width is a narrow 15.6 inches, despite the bigger, 72mm bore (stroke is 46mm). The cam drive, by silent chain, is moved from its old center position to the right side. Six crank bearings have become five.

Suzuki design is, historically, direct and simple. Having made the new engine 1.2 inches narrower to keep chassis dimensions under control, there was now room to put a tiny alternator back on the crank end, eliminating the former gear drive and its weight. The starter, only 2.25 inches in diameter and 3.5 inches long, drives the right-hand crank end from its perch behind the cylinder. This engine has a three-layer case. The cylinder assembly bolts to the upper case, and the next layer supports the crank. Under that layer lie the gearbox shafts, accessible without disturbing the crank. Finally, the bottom layer closes the gearbox, with the oil sump below that. The weight-saving campaign has been detailed and thorough, with even items like the headlight lens and speedometer receiving attention. The bolted-on, two-piece, aluminum seat subframe is attached with racing-style hollow bolts. Axles are large and generously hollow. The steering stem is aluminum. Damper parts in the 43mm inverted fork are ditto. Everything has been redone. Roomsful of engineers have sat at desks with gram scale, calipers and old parts in hand, pondering how best to lighten, simplify or eliminate. Glowing computer screens awaited keystrokes that would define the new model. In printed literature, Suzuki speaks of this bike’s more closely integrated design. Easier said than done-like Army-Navy cooperation. It calls for sustained, careful management to push competing, turfconscious departments into effective joint action. This bike says they succeeded.

A major aspect of the new GSX-R is manufacturing engineering. It’s much easier to build a $25,000 high-tech motorcycle than it is an $8999 one. It’s all too easy to rely on expensive manual methods, rather than to design for both function and economical automatic production. But the 750’s price shows that the work has been done. This is not a corporate hood ornament or unstreetable homologation special. This is a real, usable motorcycle, made affordable for real riders, to bring new levels of machine competence to real highways. It may also put Suzuki back up front in Superbike racing.

street engine (and, Hassan company riders) we might are of observed far add, England’s years more the hearts often Covcntry-Climax won ago and by that minds acceleraraces of tion than by top speed. Yet for unknown reasons, GSX-R power has been the reverse of this, existing mainly up high in the rev range. Indeed the first GSX-R achieved its revolutionary performance more by light weight than by a well-stuffed midrange. The main mission of the new T-model is to fix history and provide the missing midrange power. The hopeful signs are there, predicting a fatter, more shapely powerband, one that will accelerate.

At first glance, the 39mm carbs fitted seem intended to continue the reign of top-weighted power. Big carbs deliver the air up high, but fall dead at the bottom, right? Not these. The carburetors on this new GSX-R have computer-controlled throttle-slide lift. To make power at the top, an engine needs big ports and big carbs-but at the bottom or in the midrange, snapping open a big carburetor provokes only an apologetic cough from the engine. Traditional CV carbs try to tailor the speed of slide lift to what the engine really needs, but carburetors aren't very smart. Suzuki’s Electronically Enhanced Carburetion “knows” engine rpm, throttle angle and gear position. It lets the engine have air faster when it needs it at high rpm, and limits slide-lift rate at lower revs, preventing stumble.

The ports themselves are much smaller than the carbs-cquivalent to a 33.5mm hole. Think of the port, close to the intake valve, as a storehouse of high-energy air during intake, moving fast enough to keep rushing into the cylinder even after the piston has started to rise on its compression stroke. This intake-velocity effect is a major element in a usable midrange.

On previous GSX-Rs, the intake ports approached the engine almost horizontally, then suddenly turned down abruptly to the valves. Unfortunate for flow, this design was necessary to keep the carbs in a traditional position, under the fuel tank. On the new bike, with its forward-slanted cylinders, the ports are severely straightened, pointing almost straight up like those of the current Yamaha and Kawasaki 750s. Lift the tank, pull the airbox cover and look down the carbs with a light; you will plainly see the valves. The more streamlined the port, the smaller it can be made for a given airflow. Smaller ports make midrange.

Another ingredient is a valve-drive system that can deliver short, sudden valve motion. Short valve events boost bottom and midrange power, but a lot of valve lift is then necessary to flow air for top power. This combo of short timing and high lift asks a lot-to bang the valve open suddenly to a great height, then quickly but shocklessly return it to its seat, a hundred times a second. This calls for small, light parts, adequate spring pressure and a simple, direct drive system. All are provided.

When bore is enlarged and stroke cut to make an engine rev higher, the combustion chamber becomes wider and thinner. Combustion will take longer because it has farther to go, and has less height in which to move by its process of turbulent swirling and shredding. Suzuki literature emphasizes the hard work that has gone into speeding combustion in the new chamber. What we see most obviously is more compactness, resulting from the narrowed, 29-degree valve angle.

Suzuki’s former ram airbox was reminiscent of Ollie North’s “cosmetic government”-it was just for looks. The ram pipes were real, but they didn’t connect to anything. This new machine has the real thing: huge ram-air intakes, located one to either side of the twin headlights. They run through reinforced ports in the chassis beams to hook into a big airbox above the engine. It is now impossible lor hot, expanded air from the radiator to enter the intake system.

Engineering can be beautiful or ugly, hut this machine abounds with small, eye-pleasing details. Things like forged-aluminum foot controls, pinchbolt-type engine mounts and shapely castings. Wheel spacers are cap tive in the fork bottoms, so it's impossible for them to drop and roll away as you heft the wheel into place with one hand and try to slip in the axle with the other. There is a Ducati 916-like hinged fuel tank. held aloft with a prop rod. Instead of the old mess of parts and brackets under the seat, the battery box integrates into the plastic rear fender. Airbox, steering-head and frame bracing all compete for space but there are no losers. Packaging is close but not uncomfortable.

A full range of factory tuning and racing parts has already been shown by Yoshimura. The stated intention is to price these to sell, and to sell lots of them. There is a guarded reference to “more than 150 horsepower at 13,500 rpm.” Revolutions are upsetting. The new GSX-R's price and performance will upset other manufacturers. And, stock or modified, racing or street, this bike will subject thousands of riders to temptation they’ll find hard to resist.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontIndian Reservations

December 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsCanadian Map Reading 101

December 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCJohn Britten, 1950-1995

December 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's Euro-Only Sportbikes For '96

December 1995 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupHonda Steps-Up the Cbr900rr

December 1995