CYCLE WORLD TEST

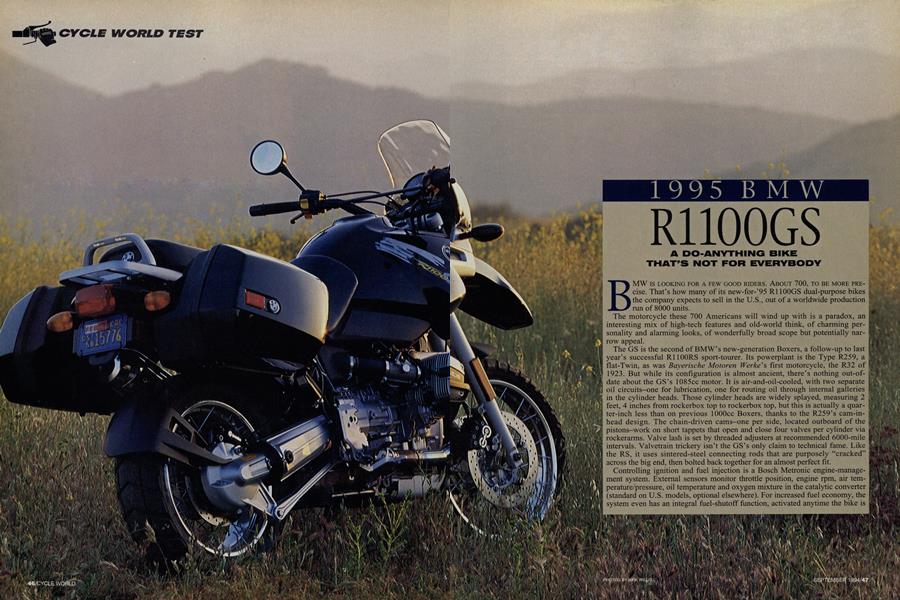

1995 BMW R1100GS

A DO-ANYTHING BIKE THAT’S NOT FOR EVERYBODY

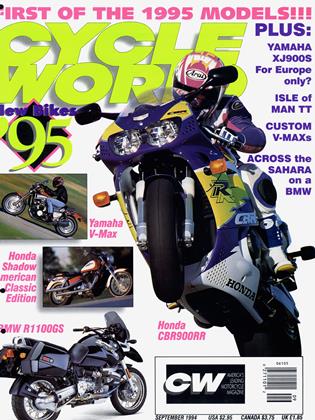

BMW IS LOOKING FOR A FEW GOOD RIDERS. ABOUT 700, TO BE MORE PREcise. That’s how many of its new-for-’95 R1100GS dual-purpose bikes the company expects to sell in the U.S., out of a worldwide production run of 8000 units. The motorcycle these 700 Americans will wind up with is a paradox, an interesting mix of high-tech features and old-world think, of charming personality and alarming looks, of wonderfully broad scope but potentially narrow appeal.

The GS is the second of BMW’s new-generation Boxers, a follow-up to last year’s successful R1100RS sport-tourer. Its powerplant is the Type R259, a flat-Twin, as was Bayerische Motoren Werke’s first motorcycle, the R32 of 1923. But while its configuration is almost ancient, there’s nothing out-ofdate about the GS’s 1085cc motor. It is air-and-oil-cooled, with two separate oil circuits-one for lubrication, one for routing oil through internal galleries in the cylinder heads. Those cylinder heads are widely splayed, measuring 2 feet, 4 inches from rockerbox top to rockerbox top, but this is actually a quarter-inch less than on previous lOOOcc Boxers, thanks to the R259’s cam-inhead design. The chain-driven cams-one per side, located outboard of the pistons-work on short tappets that open and close four valves per cylinder via rockerarms. Valve lash is set by threaded adjusters at recommended 6000-mile intervals. Valvetrain trickery isn’t the GS’s only claim to technical fame. Like the RS, it uses sintered-steel connecting rods that are purposely “cracked” across the big end, then bolted back together for an almost perfect fit.

Controlling ignition and fuel injection is a Bosch Metronic engine-management system. External sensors monitor throttle position, engine rpm, air temperature/pressure, oil temperature and oxygen mixture in the catalytic converter (standard on U.S. models, optional elsewhere). For increased fuel economy, the system even has an integral fuel-shutoff function, activated anytime the bike is coasting and engine revs are above 2000 rpm.

Because the GS is intended for less intensive speeds than the sportier RS, BMW altered its powerband. Milder cams, lower-compression pistons, a remapped ignition curve and an upswept 2-into-l exhaust have knocked power off the top end and given a stronger midrange. Hooked up to the Cycle World rear-wheel dyno, the GS churned out 73 horsepower, seven down on the RS, but produced 66 foot-pounds of torque, one up on the RS. Past our top-speed radar gun the GS, further handicapped by dirtier aerodynamics than the 134-mph RS, mustered just 117 mph. But the dual-purpose bike showed its stuff in top-gear roll-ons, besting the RS by six-tenths of a second going from 40 to 60 mph, 1.2 seconds going from 60 to 80.

On the road, the GS’s power trade-off yields a bike that is easy to ride, with plenty of poke and little need for gear shifting. Minor tweaks to the fuel-injection system seem to have all but eliminated the surging and stumbles that sometimes afflicted early-production RS models. In more than 3000 test miles, we experienced only the very occasional low-rpm hiccup.

Old-time Boxer fans will immediately recognize the distinctive low-frequency throbbing that the engine imparts at certain rpm. This is far from bothersome, but as revs get close to the 7500-rpm redline, vibration makes itself known through footpegs and seat. The solidly mounted handlebar, with weighted endcaps and rubber-isolated grips/controls, remains relatively vibe free. Effective top cruising speed for the GS is about 85 mph; above that the normally comfortable, standard-style sit-up-and-beg riding position becomes a liability.

Curiously, the bike’s windscreen drew flak from some test riders, both small and tall, for creating noisy turbulence at faceshield level, while others of the same heights had no such complaints.

Though it has benefited from the running changes made to last year’s R1100RS drivetrain-O-rings between the transmission’s gears and their shafts, tighter tolerances on the input shaft and a revised primary ratio-the GS’s five-speed gearbox still is not a model of snick-snick precision. Gear changes, especially when downshifting into the lower two cogs, are notchy. At least the embarrassing gear rattle in neutral, as displayed by CW s long-term 1100RS, has been exorcised, and clutch pull seems lighter.

The clunky transmission is the only glitch in the Type R259; though far from debilitating, it really sticks out on such an otherwise refined engine package.

No complaints about the GS’s chassis, though. Leading the way is BMW’s innovative Telelever front end, rigged for dual-purpose duty with more travel (up almost 3 inches to 7.5 inches) and a front shock adjustable via a ramp-type collar to

five preload settings. This system, basically a front swingarm hinged off the engine cases just above the cylinders, continues to impress. It is supremely supple over the small stuff, swallows big bumps without complaint and has built-in anti-dive properties. Another advantage should be reduced maintenance over a conventional fork; BMW says the only compo-

component that needs checking-every 62,000 miles-is the spherical joint that mates the swingarm to the telescoping front tubes.

At the rear, you’ll find a single, centrally mounted shock, the now-familiar single-sided swingarm and BMW’s Paralever shaft-drive system, which does away with most of a shafty’s chassis-jacking bugaboos. Wheels front and rear are spoked, laced so that the spokes pass through the rims outside the bead areas, allowing use of tubeless tires.

Michelin provides the rubber, specially designed T66 dual-purpose radiais, the rear a meaty 150/70-17, the front a 110/80-19. Brakes are by Brembo, with dual four-piston calipers squeezing 12-inch rotors up front, a two-piston unit working on a 10.9-inch disc out back. As are about 90 percent of the GS models scheduled for U.S. consumption, our testbike was fitted with BMW’s excellent ABS II antilock plumbing, a $1200 option.

All this adds up to a great handling package. Ground clearance is almost limitless, leverage provided by the wide MX-style handlebar (spanning 32 inches grip end to grip end) is generous, the Michelins stick, the suspension sucks up road jolts and braking is spectacular-both in feel and in pilot power. Down a twisty road, the GS with a good rider aboard will stay glued to the hindquarters of all but the best-ridden sportbikes. Factor in rain or bumps or sandy comers and the GS, with its ABS and dirtbike riding position, is the motorcycle of choice.

The GS is not, however, a real dirtbike, contrary to the accompanying photo of Off-Road Editor Jimmy Lewis jump-

ing the thing at the Carlsbad Raceway MX track. At 530 pounds dry, the GS is actually 10 pounds heavier than the street RS, and doesn’t take kindly to being tossed about off-road. Gravel roads and jeep trails are fine, and it’s even fun to get the back end hung out a bit on smooth surfaces, but the consequences for overexuberance in the dirt can be severe. Also, by going from a 21-inch front rim to a 19-incher, BMW has severely limited the variety of semi-knobbed aftermarket tires that can be fitted. Better to think of the GS as a streetbike with limited off-road capabilities.

Which brings us to the 1 lOOGS’s appearance. No getting around it, this new Beemer is one strange-looking mode of transportation. Had you come across it in a display case at the Smithsonian’s Air & Space Museum with a placard informing you it had been stowed in the cargo bay of Armstrong and Aldrin’s Eagle moon lander to be used as some kind of one-man lunar rover, that’d be easy enough to believe. BMW readily admits that the R1 lOOGS’s styling raised eyebrows with some of the company’s more conservative officers, but as Hans Sautter, Munich-based head of PR, puts it, “It’s okay if people say, ‘Hey, what’s that?’ To introduce a new model and have no one take notice would be bad.” And weird-Harold looks aside, there’s no arguing that the GS works very well indeed. It has proven so popular in Europe that of the 80 R259 motors BMW’s Berlin-Spandau plant pumps out each day, 64 are currently slated for GS use. In Germany, dealers are sold out of the GS until September.

Still, if you can’t get past the bike’s decisively oddball styling, or if you don’t buy into its do-it-all philosophy, or if you think $12,000 is too much to pay for a motorcycle, no matter how competent, then no amount of persuasion will convince you to liberate an RI 100GS from your local Beemer emporium. But if you’re looking for a motorcycle that functions

equally well as a new-age standard, an everyday commuter, a two-up tourer, a backroad blitzer and a light-duty dirtbike, there’s really only one model on the market that fills the bill. And BMW has 700 of them ready to go. □

EDITORS' NOTES

IF I WERE LOOKING FOR A STREETBIKE TO take on a long trip, this would be the one. One reason: It’s the only good streetbike that you can safely ride offroad. Don’t get me wrong, or let those crafty BMW ads fool you, this is in no way a dirtbike. But it will navigate, using extreme caution, a dirt road that is passable by two-wheel-drive vehicles. And I can’t think of a better way

to take a long trip than to include some dirt roads.

As for performance, well, I like how the Beemer carries a lot of fuel, how the ABS can be deactivated off-road and how the GS can pack way more luggage than any other dual-purpose bike. I don’t care for the windscreen that buffets my head like a loser in a pillow fight, and shedding a hundred pounds wouldn’t hurt the bike, either. But I’m not the designer, I just ride ’em.

So on my next ride through Death Valley or some other out-of-way place-provided I don’t plan on getting too carried away with off-road excursions-ITl be GS’n it.

-Jimmy Lewis, Off-Road Editor

SORRY, FRIENDS, I JUST CAN’T APPRECIate this beast. Yeah, I know, the RI 100GS has all the right stuff, including an absolutely revelatory front suspension and a terrific engine. Sorry, that doesn’t get it. First of all, the thing is cursed with styling only a German could love. I mean, look at it: That weird proboscis of a front fender, the enormous castings that carry the foot-

pegs. Hey, BMW, it’s okay for motorcycles to be beautiful. Really. I wouldn’t kid you.

Secondly, the GS is huge, absolutely enormous, equipped with a handlebar wide enough to challenge my reach-and I’m 6-foot-4, long of leg, arm and torso. If Germany grows motorcycle riders big enough to fit this thing, I’d love to see its basketball teams.

Does the RI 100GS work? Yes, of course it does, gobbling up road like the very thoroughly developed piece of quality equipment it is. Is that enough? Not for me, it isn’t.

-Jon F. Thompson, Senior Editor

To ME, BMW GS MODELS HAVE ALWAYS been ’round-the-world bikes. Sure, they’re good at almost anything, but their real purpose is to wait patiently in the garage until that day comes when you quit your job, cash-in the profitsharing plan, board the dog, load up the survival gear and head for points (and adventures) unknown. Tierra del Fuego or Bust...saddlebags ready to accept

flag decals of the countries I’d cross...freelance feature stories filed from Cairo...or Kiev...or Kenya.

Previously, I’d have picked a Paris-Dakar R100GS (like the standard GS available for at least a couple more years) for that duty. But the Telelever front end and an extra 20 horsepower have swayed me toward the new 1100.

I’ll probably never take off like the Bramsens, whose GS adventure you can read about starting on the next page. All the same, make my R1100GS Marrakesh Red with the optional international safety-yellow seat-just in case I get stuck in the Sahara and they have to send out search planes to find me. -David Edwards, Editor-in-Chief

BMW

R1100GS

$11,890

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontNotes From the Alps

September 1994 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsRiding Home

September 1994 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTime To Burn

September 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1994 -

Roundup

RoundupTriumph Thunderbird Set To Soar?

September 1994 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupLaverda Plans New Bikes

September 1994