I’D HAVE GIVEN ANYTHING to see the faces of the Cycle World staff after the first day of this year’s Nevada Rally. The press release faxed to the office said, “Cycle World Magazine editor wins Day One.” Well, hey, my job description for the week was to be a racer in the Acerbis Nevada Rally. Apparently I was doing a hell of a job.

At least things were going a bit better than they did in last year’s Nevada Rally, when the first call home was a plea to Editor-in-Chief Edwards to let me quit after blowing up two motors. This year I decided to do things a little differently. First, I got a factory ride. I wangled a full-blown, first-class, everything-included Honda off-road ride through Honda’s Rally Rental program, available to anyone willing to pony up its $10,000 price. Second step was a good dose of riding time (read: testing lots of new dirtbikes) to get in proper rally shape. The third and final preparation step was to get a good finish in the opening Prolog section to keep dust-chasing to a minimum.

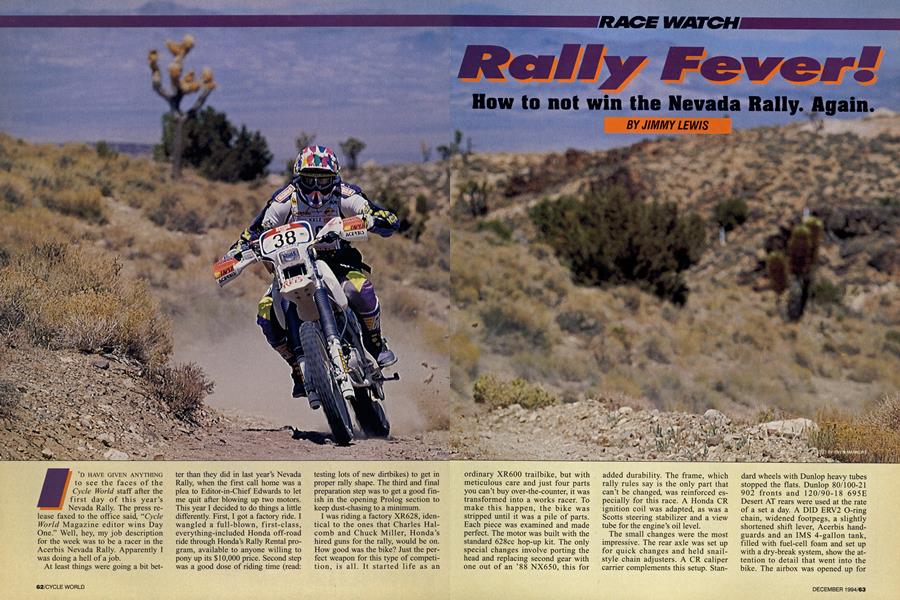

I was riding a factory XR628, identical to the ones that Charles Halcomb and Chuck Miller, Honda’s hired guns for the rally, would be on. How good was the bike? Just the perfect weapon for this type of competition, is all. It started life as an ordinary XR600 trailbike, but with meticulous care and just four parts you can’t buy over-the-counter, it was transformed into a works racer. To make this happen, the bike was stripped until it was a pile of parts. Each piece was examined and made perfect. The motor was built with the standard 628cc hop-up kit. The only special changes involve porting the head and replacing second gear with one out of an ’88 NX650, this for added durability. The frame, which rally rules say is the only part that can’t be changed, was reinforced especially for this race. A Honda CR ignition coil was adapted, as was a Scotts steering stabilizer and a view tube for the engine’s oil level. better ñow and a carburetor boot from the ’88 XR600 was used for its rounder shape. K&N filters kept dirt out of the engine. A large oil cooler mounted on the lower triple-clamp cooled oil on its return trip to the holding tank on the frame. Wiring was installed to run the auto-scroll map-book and the required brakelight. Pro-Taper handlebars with CR levers and perches gave me a firstclass cabin; aiding the feel was a Ceet-built saddle with a taller-thenstock profile and special vibrationdeadening foam.

Rally Fever!

How to not win the Nevada Rally. Again.

RACE WATCH

JIMMY LEWIS

The small changes were the most impressive. The rear axle was set up for quick changes and held snailstyle chain adjusters. A CR caliper carrier complements this setup. Standard wheels with Dunlop heavy tubes stopped the flats. Dunlop 80/100-21 902 fronts and 120/90-18 695E Desert AT rears were used at the rate of a set a day. A DID ERV2 O-ring chain, widened footpegs, a slightly shortened shift lever, Acerbis handguards and an IMS 4-gallon tank, filled with fuel-cell foam and set up with a dry-break system, show the attention to detail that went into the bike. The airbox was opened up for

Suspension components were standard, but the shock body and fork sliders had been hard-anodized to minimize oil contamination. The shock had the stock spring, but with lighter compression and faster rebound settings than stock. The fork used stiffer springs and altered valving. The left fork leg and the stanchion tubes were some of the few unobtainable parts on the 628. The left lower leg was identical to stock but with a pinch-clamp setup to allow the use of a quick-change axle. The stanchion tubes were a half-inch longer than stock for additional chassis-geometry adjustability. The lower triple-clamp was a billet-machined piece for better grip on the fork legs. The final special piece was a wheel spacer made of aluminum (instead of steel) to prevent problems that come with overtightening the rear axle.

The result was awesome.

With mere minutes of stick time on the bike, I managed to tie for the Prolog win with Jeff Capt, another Honda rider. I would start a minute behind first-time rally rider Capt followed by Chuck Miller, French Honda rider Richard Sainct and Enzo Manetti of Italy. I was right where I wanted to be.

During a 160-mile pavement transfer section from the Las Vegas area to Beatty, everything was working perfectly. By the time I reached Beatty, I was relaxed, confident with my mapbook reading skills, pleased with the bike, and fairly familiar with the desert terrain of the first special test, Beatty to Tonopah, 216 miles through the 100-degree Nevada heat.

Then I was off, one minute after Capt. There was just enough wind to clear the dust as I roosted around the outskirts of Beatty. I passed a few curious townspeople, several knots of world-press camera crews and was finally out into the open desert. Right after the edge of town, Capt missed a turn and I found myself in the lead. Instantly, there was a helicopter, cameraman hanging out of the window, following me. I was making the trail now, leading the best rally riders in the world. I was nervous.

From my many “what-if” scenarios, I pulled out Plan Number One: Haul ass and put time on the field so I could slow down and think. Opening up the big XR to speeds right around the 100-mph mark turned the desert into a blur. About 15 miles into the course, I looked back to get a feel for how I was doing, saw that I had a sizable lead and that there was so much dust that no one was going to pass me through it. I slowed down, screwed my head on and started concentrating on not making any mistakes. This is tough. Riding an unmarked course at speed, determining turns from only the map book, can be psychologically tiring. The miles started piling up-50, 100, 150-and everything went smoothly. I was staying on course, making each gas stop, which my pit crew accomplished each time in about 7 seconds. I was on my way to an accomplishment that pleases me greatly: I won the special test and the day overall. Winning an ISDE special test was a goal I never achieved. This will do. I was the leader of the rally, wearer of the Gold Bib. Most important, I’d start first the next morning.

One of my teammates for the event, Chuck Miller, finished second overall close to 6 minutes behind me. Last year’s winner, Frenchman Alain Olivier, was third on the day, 7-and-ahalf minutes back.

Scary. I’d turned from mild-mannered Off-Road Editor to motivated Racer and hardly noticed the change. I wasn’t thinking about how to write this story. I was thinking about how to win this rally. Focused, that’s what I was. Focused at the riders meeting, focused on helping my mechanic, Red Austin, make all the right adjustments to my bike. I was so focused that I couldn’t sleep. I was a racer again.

My Day Two plan matched that of Day One: ride smart, no mistakes. After a last-minute map-book problem-my map roll didn’t fit into the holder until a flock of Honda mechanics made it fit-I was on the line just 5 seconds before my start time. I compounded the tension by blowing the first turn in the map book. It was two-hundredths of a mile from the start-that’s about 20 steps. Instead, I went hauling down the road looking for a turn two-tenths of a mile away. Sanity finally overpowered panic and I went back, made the turn and progressed onward without losing much time or a position. I got back on track and the first 50 miles went smoothly. All was according to plan. Then I made my first big mistake.

A wrong turn is a serious problem, especially for the first bike through, with no tracks to follow. I made one. Rampant confusion followed. For about 10 minutes-enough to let six riders by-I rode around trying to make sense of my directions. Miller now had the lead. He did, that is, until he also made a wrong turn about 5 miles past mine.

So, how hard is it to read the map book at speed? Look at it as trying to split lanes on a Gold Wing going 50 mph above the speed of traffic. While reading a mini-novel. For 4 hours straight. And you’d better be able to write an A+ book report when you finish. It’s a true skill.

This is where Olivier made his time. He made all the right turns and took the lead. I was back in the dust again, picking my way back to where I had been. This took all day as our 298mile special test took us toward Fallon, in the west-central part of the state.

I endured the dust, passing riders as they either got lost or stopped for pit service. The last 20 miles, I was closing on Olivier and Heinz Kinigadner, who were sharing the lead. To my surprise, they blew a turn nearing the finish. What goes around comes around. After a little interpretation of the map, I got on the right course, followed by Johnny Campbell, Miller, Halcomb and Davide Troili. Olivier realized his mistake and made a correction. But now his bike’s odometer was off, making it difficult for him to find the remaining turns. In a bit of confusion at the end of a dry lake bed, I grabbed the physical lead and found the way to the finish, followed by seven other riders who finished within a minute of me. Honda’s Halcomb took the day’s win, with Austrian KTM rider Kinigadner and Italian Kawasaki-mounted Trolli right behind.

Not a bad recovery. I would be starting seventh on Day Three, though I still had the overall lead, the Gold Bib and a 5-minute cushion. Cool. I was used to following the dust, and I found it to be less stressful than leading. I was a little less nervous.

Day Three was a bad one. I made three mistakes, and they cost me a shot at winning. The first came about 100 miles into the day’s 300-mile test. Everything was going smoothly and I was catching the rider in front of me on a very fast road. Pushing a little too hard, I slid off the road a few times, braking for turns. I kept telling myself, “Slow down’’ but I didn’t. Luck ran short. A rock in the wrong place at the wrong time put me into a series of 70mph cartwheels and delivered an I’llbe-sore-tomorrow pounding. But I was in trouble beyond that. The flipping XR crushed the map-book holder into uselessness and I was forced to follow tracks on the ground, which at speed can be very difficult.

This led to another mistake. I got well and truly lost. At a turn, three tracks went one way, two the other. I chose the route with three tracks. A mistake-one that cost me 30 minutes. With help from Kinigadner, who was lost with me, and Stephan Peterhansel, who we found going the right way, we got back on track. But I lost my lead in the process. Olivier was now ahead of me by more than 20 minutes, which meant he’d start the next day with the Gold Bib. My Gold Bib. I was now third overall behind Campbell, the other rider to find the correct route.

Bummed? That hardly describes it. But hey, this was a rally. Anything could happen. Couldn’t it? Speed alone was in no way going to move me back up to the front position. But anyone, even Olivier, could get lost.

The next morning, I played it safe in third place, gaining a little here and losing a bit there. Fourth-place runner Kinigadner was 12 minutes behind me, a huge amount of time that would be hard for him to make up.

Olivier, meanwhile, was just where he wanted to be. Second-place Honda rider Campbell had a bit of speed on Olivier, just enough to make last year’s winner nervous. So the Frenchman laid a trap. Not confident in his map-book reading skills, Campbell was happy to follow the Kawasaki rider’s dust and prey on Olivier, waiting for a mistake that would allow him to inherit the lead. But Olivier is a sly one. He purposely blew a turn and led Campbell off route. He then hopped off his bike as if he was having a mechanical problem. Campbell saw this as the window of opportunity and jumped into the lead, not knowing that he was roosting off-course and farther behind, instead of farther ahead. Once Campbell was out of sight, Olivier returned to the correct route and continued on.

“I didn’t even realize what he had done. He got me,” an embarrassed Campbell said later. In so doing, Olivier gained a precious 3 minutes with which to pad his lead.

Kinigadner, meanwhile, turned up the wick, thereby disproving a generally accepted myth that the ex-worldclass motocrosser couldn’t read a map book. He took the day’s specialtest win, his first after years of rally competition. I actually had a betterthan-expected finish, second place for the day, though I didn’t dent the lead of the front-runners. Finishing third for the day was Halcomb, making up serious time after getting lost even worse than I did the day before.

Next came a rest day in Ely, an old mining town in central Nevada. Great. The sky opened and thunderstorms made it difficult to catch up on sleep, an incidental that falls through the cracks during the course of an off-road rally. Mechanics, meanwhile, passed their time performing full-bike overhauls.

I was actually looking forward to riding on the wet ground the next day. Kinigadner took off first, his rear knobby virtually painting a line on the course. The riders following would only have to use the map-book for confirmation, able to follow his tracks without dust. As the fast guys caught up, a group formed at the front, with each rider taking turns leading. I settled back, playing follow-the-trail and hoping to find the big turn everyone else missed. It never happened. The day was broken into two special tests, the first of which was taken by a hardcharging Campbell. The second test was won by Halcomb, with the day’s > overall going to Campbell, the fifth different rider to win a day. Olivier still had the Gold Bib and a 5-minute cushion. There was just 100 miles of racing to go.

But 5 minutes is only one small mistake, and both Campbell and Olivier knew it.

Campbell was first off the next morning for the loop section around Mesquite. Campbell’s novice map skills were all Olivier needed to quickly catch the Honda rider, who was content to follow. Starting back in fifth, Kinigadner had his own idea of how to ride the final test. Unlike last year, when his rally ended with a helicopter ride to the hospital for treatment of a broken collarbone, this year he was on a mission to win. Kinigadner took the lead about 40 miles out, and dragging a still-hopeful Campbell along, basically motocrossed through the thundershower-drenched Mojave Desert to the finish. But in the end, nothing changed.

Olivier had won his second Nevada Rally. Campbell the rookie hung on for second, serving notice that when his map-book reading comes along, he’ll be dangerous. Me? I also wound up on the podium. Third. A sweet feeling, especially for a journalist exracer. Kinigadner tried hard to get me, but only managed five of the 12 minutes he needed.

Olivier said of his win, “I had the plan to start out slow and take the lead later in the week. I know from other rallies the early leader never stays for the win. I am very happy for my second win.”

Well, fine. That was me he was talking about. If only I had, in the course of my magazine duties, interviewed him before the race and heard his plan. Now, I sit here in front of my word processor, reviewing all the “I coulda, shoulda, woulda” ways that I coulda, shoulda, woulda won the 1994 Nevada Rally.

Maybe next year. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

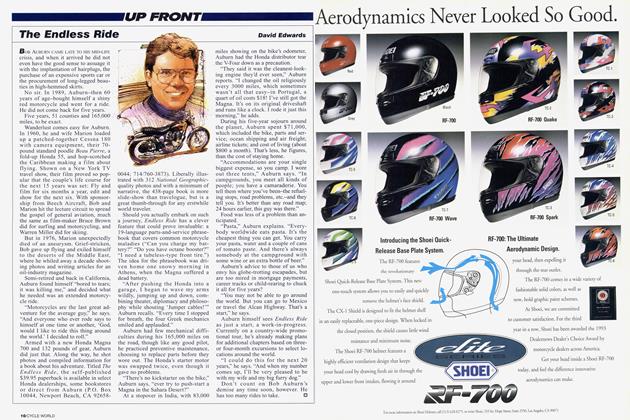

Up FrontThe Endless Ride

December 1994 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsSaving For A Vincent

December 1994 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCCharacter Assassination

December 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1994 -

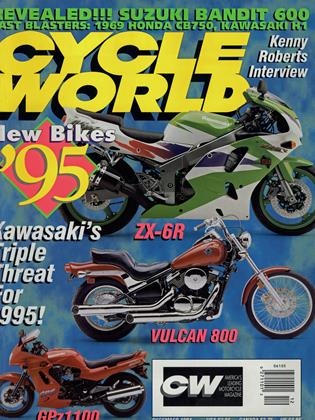

Roundup

RoundupAt Last! Suzuki Shows A Bigger Bandit

December 1994 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupCw In Cyberspace

December 1994