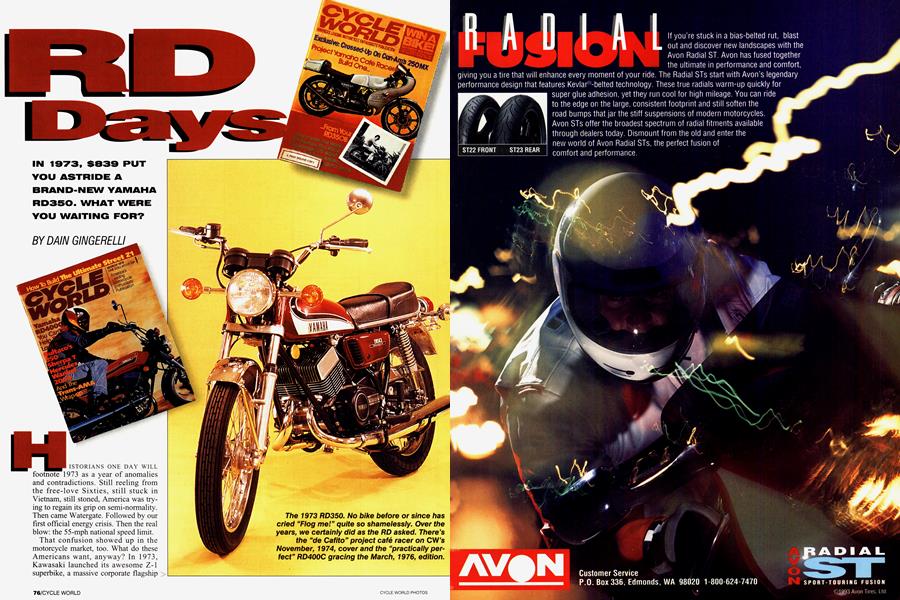

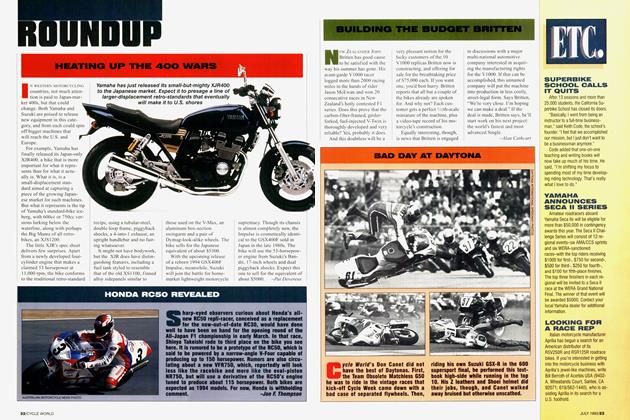

RD Days

IN 1973, $839 PUT YOU ASTRIDE A BRAND-NEW YAMAHA RD350. WHAT WERE YOU WAITING FOR?

DAIN GINGERELLI

HISTORIANS ONE DAY WILL footnote 1973 as a year of anomalies and contradictions. Still reeling from the free-love Sixties, still stuck in Vietnam, still stoned, America was trying to regain its grip on semi-normality. Then came Watergate. Followed by our first official energy crisis. Then the real blow: the 55-mph national speed limit.

That confusion showed up in the motorcycle market, too. What do these Americans want, anyway? In 1973, Kawasaki launched its awesome Z-l superbike, a massive corporate flagship of a machine. Yamaha, meanwhile, took a different tack. While other companies downplayed and phased out their two-stroke product line, the people from the tuning-fork company revamped their twin-cylinder two-strokes, spearheading the movement with a machine that lives on in the hearts and minds of aging street-squids everywhere.

It was called the RD350.

The RD was not a totally new model, but an evolution of the 350cc R5 of 1970, itself a big evolutionary jump from the cumbersome YR-1. The new RD was simply an improved R5, with noticeable refinements to chassis and engine. The RD350 came with a dual-piston front disc brake that “generated enough decelerative force to jerk your eyeballs out,” according to Cycle magazine. It was the hardest-stopping streetbike money could buy. Both RDs (there was a 250, too) got close-ratio, six-speed gearboxes, and reed-valve intake systems labelled “Torque Induction” by Yamaha’s marketeers. The line of demarcation between R5 and RD350 was most clearly drawn in performance: The RD zipped through the quarter-mile over a second faster than the R5, with 9 more mph in terminal speed-14.3 seconds at 89.8 mph.

Numbers aside, the RD really excelled in the real world. Especially if your world consisted of twisty roads, where an aggressive RD rider could wreak havoc on bigger motorcycles. Balance was the key. Multi-link rear suspensions, upside-down cartridge forks, twin-spar aluminum frames-none of those things were yet conceived. Instead of high technology, Yamaha engineers depended upon the savvy accumulated from years of building roadracers that had thoroughly dominated 250 and 350cc classes worldwide.

The same engine cases used in the R5/RD could slip right into Yamaha’s TD2 250 or TR3 350 roadracers. Motor mounts were identical, and production and racebikes used similar doubledowntube cradle frames. (The race frames actually used thinner-wall tubing than the street bikes, for lightness.) Numerous club racers resuscitated dying TD2/TR3 racers with RD heart transplants, the donor often as not a wadded production or café racer.

But even in stock trim, the RD was a sizzling performer. In addition to having frame dimensions similar to those of the racers, RDs received additional bracing and gusseting in the highstress areas around the steering head, engine mounts and swingarm. The result was a frame that wouldn’t flex, wobble or shimmy when a rider pointed it at an apex; the RD was one of the most sure-footed bikes of the time.

Well, sure-footed provided you sat forward to weight the front end, and provided you didn’t mind a slight amount of twitchiness after turn-in. With 45/55 front-rear weight bias, and

not much trail, the RD tended to dance through turns. Sitting forward, motocross-style, gave better feel and calmed the bike. That rearward weight bias also contributed to what may be the RD’s main claim to legendary squidliness: It was the best wheelier of all time. Ready or not, wheeeEEEEEE! Hey, don’t blame us for your road rash; we warned you back in ’74: “The yo-yo who climbs on an RD350, revs the engine up and dumps the clutch, will be on his back so fast it will make his head spin.”

While it could turn comers quicker than a mouse in a maze, the RD had one major shortcoming when leaned over. It dragged its footpegs and their very solid brackets mercilessly. Rearsets were a common modification among the go-fast crowd (though many racing organizations wouldn’t allow them in production classes).

Within days, it seemed, an entire cottage industry catering exclusively to the little roadster sprang up, and RDs sprouted expansion chambers, multitudinous carburetor adaptations, lowslung handlebars, fiberglass fairings, seats and tanks, and all manner of custom port jobs. Cycle World even got in on the act and built one. Called “Yamaha de Cafito,” it graced the cover in November of ’74.

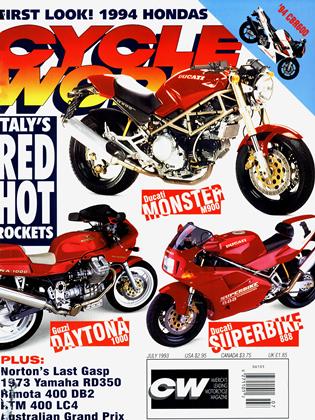

With EPA noise and clean-air standards closing in during the midSeventies, it was only a matter of time before the two-stroke streetbike became a two-wheeled dinosaur. But in 1976, Yamaha fought back with the RD400C.

While the 400 was essentially a brand-new motorcycle, its lineage was plain to see. Bores remained 64mm, while stroke grew to 62mm. Bypass holes in the cylinders and cutaways in the piston skirts reduced low-end surge and quieted the bike somewhat at lower rpm. While 28mm Mikunis were still used, they were redesigned for lower emissions.

With the RD400, Yamaha became the first major manufacturer to equip a bike with alloy wheels. The caliper for the “eyeball-popping” front disc was moved to the rear of the fork leg for better handling, and an identical disc was fitted to the rear wheel. Suspension got better: Teflon bushings reduced stiction in the fork, and improved shocks were fitted out back.

The engine was moved eight-tenths of an inch forward, resulting in better handling and slightly fewer wheelies-and making room for a larger airbox that toned down intake honk. A new oilinjection pump allowed up to 500 miles on a quart of Castrol, where the 350 usually went dry after only about 150 miles. The engine, handlebar and footpegs were all rubber mounted.

The end result was an improved, more refined RD for street use. “The closest thing to a perfect motorcycle,” we wrote in our March, 1976, road test. The only quibble we could find concerned the hom: “The standard unit wouldn’t make a hungover wino flinch, let alone inform some quadrophonically deafened cigar-puffing lardo that he is blindly stuffing his gassucking smogmobile into the lane you are occupying.”

In ’78, Yamaha’s ad for the RD, following 10 pages of four-stroke propaganda, was headlined: AND NOW, OUR 2-STROKE STREET LINE. There sat a silver RD400, all alone. Somebody at Yamaha apparently cared about the RD as much as we did; they wouldn’t let it die quite yet.

Death was imminent, though. One year before the EPA edict of 1980, Yamaha sprang the RD400F Daytona Special, complete with emissions-control valves, chassis upgrades, a restyling job-and finally the damn footpeg brackets were moved out from under the mufflers. Even running a bit cleaner (and suffering at any throttle setting other than fully open) the RD was still good for 14.18 at 91.4 mph at the dragstrip. And you could still port, pipe and carbúrate the thing easily into the 12s.

The Daytona would be the last true RD, and when it reappeared in ’85, disguised behind a radiator and called RZ, well, it just didn’t matter so much anymore. After ’86, the RZ was gone, too.

Will we ever see, in America, the likes of the RD again? Engineers at major auto-makers have taken a keen interest in two-stroke technology for cars of late, and electronic fuel injection now makes clean-running twostrokes feasible. There is hope, however faint, that valveless motorcycles will return. If the two-stroke does come back, don’t be surprised if the bike sports a trio of tuning forks in its logo, sounds like a really big bee, and spends a lot of time on one wheel. □

A former Cycle Guide staffer, Dain Gingerelli started racing in 1968 at the age of 15, happily hasn ’t matured a bit since, and now deals with anything on wheels as a freelance journalist.