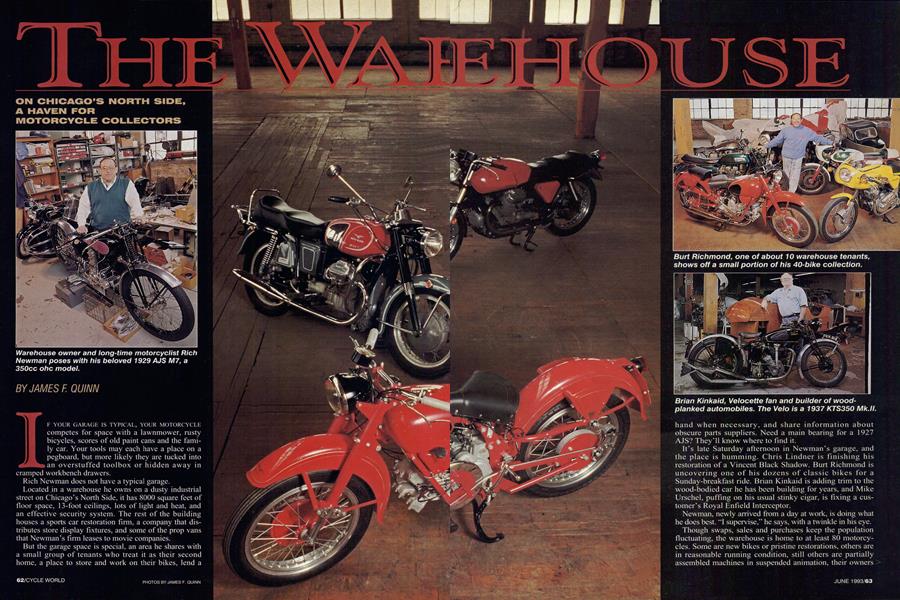

THE WAR EHOUSE

ON CHICAGO'S NORTH SIDE, A HAVEN FOR MOTORCYCLE COLLECTORS

JAMES F. QUINN

IF YOUR GARAGE IS TYPICAL, YOUR MOTORCYCLE competes for space with a lawnmower, rusty bicycles, scores of old paint cans and the family car. Your tools may each have a place on a pegboard, but more likely they are tucked into an overstuffed toolbox or hidden away in cramped workbench drawers.

Rich Newman does not have a typical garage.

Located in a warehouse he owns on a dusty industrial street on Chicago’s North Side, it has 8000 square feet of floor space, 13-foot ceilings, lots of light and heat, and an effective security system. The rest of the building houses a sports car restoration firm, a company that distributes store display fixtures, and some of the prop vans that Newman’s firm leases to movie companies.

But the garage space is special, an area he shares with a small group of tenants who treat it as their second home, a place to store and work on their bikes, lend a hand when necessary, and share information about obscure parts suppliers. Need a main bearing for a 1927 AJS? They’ll know where to find it.

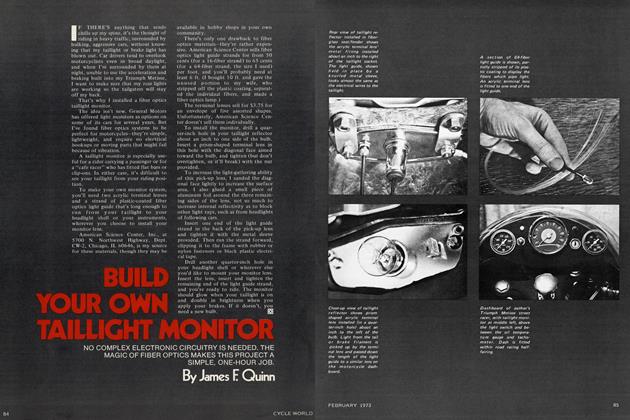

It’s late Saturday afternoon in Newman’s garage, and the place is humming. Chris Lindner is finishing his restoration of a Vincent Black Shadow. Buít Richmond is uncovering one of his dozens of classic bikes for a Sunday-breakfast ride. Brian Kinkaid is adding trim to the wood-bodied car he has been building for years, and Mike Urschel, puffing on his usual stinky cigar, is fixing a customer’s Royal Enfield Interceptor.

Newman, newly arrived from a day at work, is doing what he does best. “I supervise,” he says, with a twinkle in his eye.

Though swaps, sales and purchases keep the population fluctuating, the warehouse is home to at least 80 motorcycles. Some are new bikes or pristine restorations, others are in reasonable running condition, still others are partially assembled machines in suspended animation, their owners waiting for parts, time, money or all three to put them back on the road. YouTl find a few Japanese motorcycles and at least two Honda Helix scooters in the garage, but they are far outnumbered by such British and European nameplates as AJS, BSA, BMW, Ducati, Moto Guzzi, Panther, Velocette and Vincent.

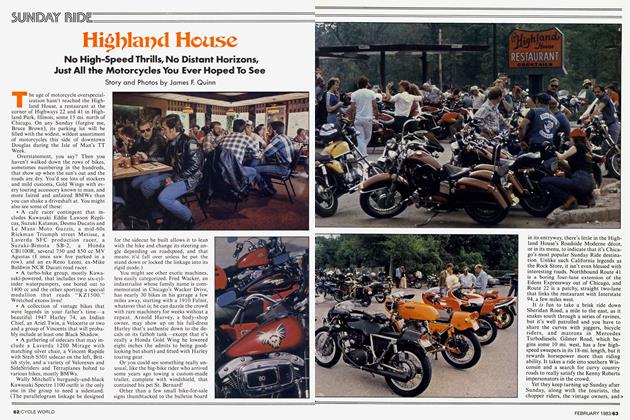

Long-time tenant Brian Kinkaid finds the warehouse a great place to work.

“It’s very friendly, with a certain amount of male tension and a little bit of bullshit,” says the semi-retired art director and illustrator. “Everyone’s very careful not to get too close, but we lend stuff back and forth. It’s a very good setting for the creative process.”

Besides his wood-planked 1932 1.5-liter Invicta sedan, Kinkaid keeps a 1937 Velocette 350, a disassembled 1951 Ariel Square Four and a 1975 Ducati 860 GT at the warehouse. Lie is entranced by Velocettes in particular. “They are simple but nicely done, with, of course, enough maddening idiosyncrasies to keep them interesting,” he says of the Velos he has owned. Next on ins acquisition list is a 499cc Venom Single. “I don’t need a bike that’s any faster than a 500 Velocette,” says Kinkaid. “The Velocette is a period piece. So am I.”

Newman has been landlord to his friendly collection of gearheads since the late 1970s, sharing space at another Chicago site before moving to the present location in 1987. The idea made sense, he says; many of his friends had motorcycles stored in garages near their homes, just as he did, and it seemed much more convenient for everyone to share space.

Burt Richmond, an architectural consultant with the largest motorcycle collection in the garage, explains: “Working out of a toolbox is very tough, especially if you live in an apartment and have no garage of your own. It starts with needing a vise, another set of hands. This warehouse is not so much a toy box as a place to work.”

Newman's own fascination with mechanical devices began in his teens with model airplanes. Soon, he had graduated to a BSA 250, then to a 750 Honda, before switching to BMW Twins.

“There was not a better highway bike in the world in the late 1970s,” he says. As a collector, Newman has owned a variety of rare machines, including “Rumblegutz,” a Vincentbased British dragbike, and a trio of Broughs, one with a banking sidecar. He sold one of the Broughs, a 680cc Black Alpine model, to comedian Jay Leno several years ago. His current collection includes a Velocette with matching sidecar, a Honda GB500 Single, a pair of AJS 350s and a 1925 center-hub-steered Ner-A-Car, which he keeps on display in his living room.

Richmond, who was featured in a July, 1987, Cycle World article when he was importing Russian-built Neval motorcycles and sidecars, guesses that he has owned more than 300 motorcycles. His collecting mania began after visiting the annual Auto Jumble at England’s National Transportation Museum in the early 1970s. Amazed by the number and variety of machines for sale, he returned the following year and bought 30 motorcycles and two cars, enough to fill a shipping container for the return trip home.

Richmond says he lives below his means on purpose so he can afford his rolling toys. Still, following his move to Chicago a few years ago, he began to whittle down his collection. He still has a 1937 Sunbeam Model 8, a 350cc Single, from his first British buying trip, but most of the 40odd motorcycles he currently keeps in the warehouse are British or Italian machines from the 1950s or later.

Richmond entrusts much of his restoration work to Chris Lindner, who impressed him a few years ago by repainting a pair of Triumph tank badges in the correct light-beige background color, a hue Lindner concocted using a combination of white paint and English tea.

Lindner, an Australian who moved to Chicago with his parents as a young man, studied film making in college, then spent eight years as a freelance artist and art director, a job he found “tedious and boring,” before becoming involved in cars and bikes. Now, he seems obsessed with his restorations, working alone, often starting at 3 or 4 a.m. with whatever project is at hand, an arrangement made easier since his recent move into an apartment above the garage space.

“I’m addicted to this work,” Lindner says. “I like taking things apart and putting them back together.”

He has spent the last year restoring a 1952 Vincent Black Shadow for Chicago collector AÍ Phillips, slowed for several months as fellow tenant Mike Urschel, who rebuilt the bike’s engine, ran into parts-supply problems.

Lindner and Urschel share a passion for motorcycles, though they approach their repair and restoration from different angles. Lindner, a relative newcomer to the garage, keeps his workbench as neat and clean as the motorcycles he restores. Urschel, one of Newman’s original tenants, has a workspace that could be charitably described as chaotic, and the bikes that emerge from “Urschel’s Friendly Royal Enfield Service” often appear as time-worn as the day they arrived for repair.

But they run, a trait that impresses Urschel and his hardy customers far more than fresh paint and shiny chrome. He says he’s capable of producing a perfect cosmetic restoration, but after more than 20 years of wrenching on English motorcycles and cars, he prefers a sort of mechanical triage, fixing what’s broken and generally leaving weathered-butworking parts alone. He recently told a customer, for example, that her high-mileage Triumph 500 wouldn't suffer after losing a valve cap as long as she could keep the oil in and dirt out. He was delighted soon after to see that as a temporary fix she had covered the valve port with aluminum foil.

A capable musician on guitar, banjo, mandolin and fiddle, Urschel worked for a time as a backup guitar player with the likes of Arlo Guthrie and Jimmy Buffett before moving into music production and management in a variety of Chicagoarea clubs. The late-night entertainment scene determines his working hours as a mechanic; he usually doesn’t show up at the garage until late afternoon, announcing his arrival by firing up the day’s first cigar, a Parodi, its stench as much an Urschel trademark as his well-worn lab coat.

He still owns his first motorcycle, a 1965 Royal Enfield 750 Interceptor, though it’s laid up at the moment after 87,000 miles of hard riding-he says he hates working on his own bikes. He also owns a Vincent Black Shadow and an array of Royal Enfields, including a rare Rickman-framed model.

Despite the reputation for unreliability that British machines have earned over the years, Urschel finds his bikes to be “dead reliable; you don’t have to screw around with them. I wouldn’t have them if they weren’t.” That attitude carries over to the work he does on customer machines; Urschel prides himself on a lack of repeat business. “If the work is done right, you won’t see the people again,” he says.

Like many of his customers, Urschel rides all year long, even through Chicago’s harsh winters. “If it’s really cold, I won’t ride because the engines never really warm up and the road salt eats them,” he says, “but I treat my bikes like everyday machines.”

Not so with Andrzej Fusiarski, another warehouse tenant. A line of partially assembled Triumphs and BSAs help to define Fusiarski's workspace, but although he rebuilds British bikes to sell at auctions, he admits to riding a 750 Suzuki. “British motorcycles are only for fun,” he says.

Fusiarski was an international truck driver in his native Poland, driving big rigs into Russia and Yugoslavia, before moving to this country six years ago. He worked on Honda and Toyota cars for awhile, then began building old Britbikes for Motorcycle Specialties, a Chicago firm that sells the bikes at auction throughout the country. He and several friends take the bikes apart, spraypaint the frames, then reassemble them with new or used parts, guided by a well-thumbed set of shop manuals he keeps in a workbench drawer. Sometimes he’ll build his own muffler brackets or other parts when they’re otherwise unavailable.

Earlier bikes, such as pre-unit Triumphs, attract more buyers than later models, but Fusiarski finds that overall the classic bike market is down. A few years ago, he says, even a badly restored Vincent from England or France would sell in the high-$20,000 range. These days, even a high-quality restoration brings less.

Art appraiser and warehouse tenant Jim McDonald is out of the classic-bike market for now. He recently sold his last motorcycle, a beautifully restored BMW R60 with a matching Steib sidecar, marking the end to a major collection. At one point, McDonald owned 12 BMW sidecar outfits, including a VW-powered rig, a 1926 model and two German Army R75s complete with machine-gun mounts.

Now an avid member of the Antique Automobile Racing Association, McDonald spends his garage time tending to his brace of vintage dirt-track cars. So far, he hasn't missed owning bikes, though he has thought about trading his restored Chevrolet pickup truck for a Harley-Davidson Knucklehead like the 1947 model he once owned.

Whether it’s cars or motorcycles, though, McDonald admits that the collecting habit he shares with his fellow tenants in the warehouse is hard to break. “There’s a lot of sickness in here,” he says with a smile, “but it’s a sickness you don’t die of. It just leaves you broke.” □

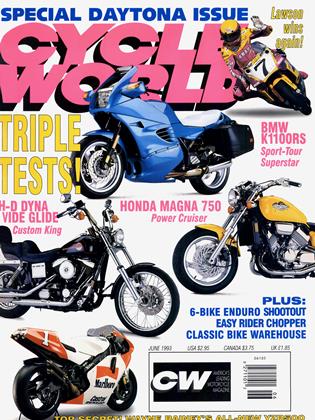

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontExit the Ogre

June 1993 By David Edwards -

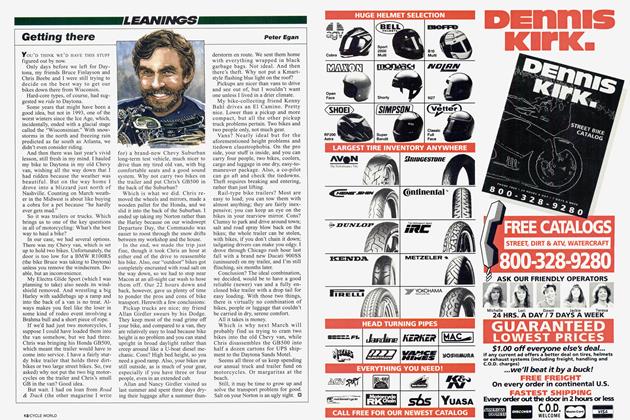

Leanings

LeaningsGetting There

June 1993 By Peter Egan -

When Pigs Fly

June 1993 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1993 -

Roundup

RoundupMz Set To Invade United States

June 1993 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupJapan's Retro-Racer Revival Continues

June 1993 By Pat Devereux