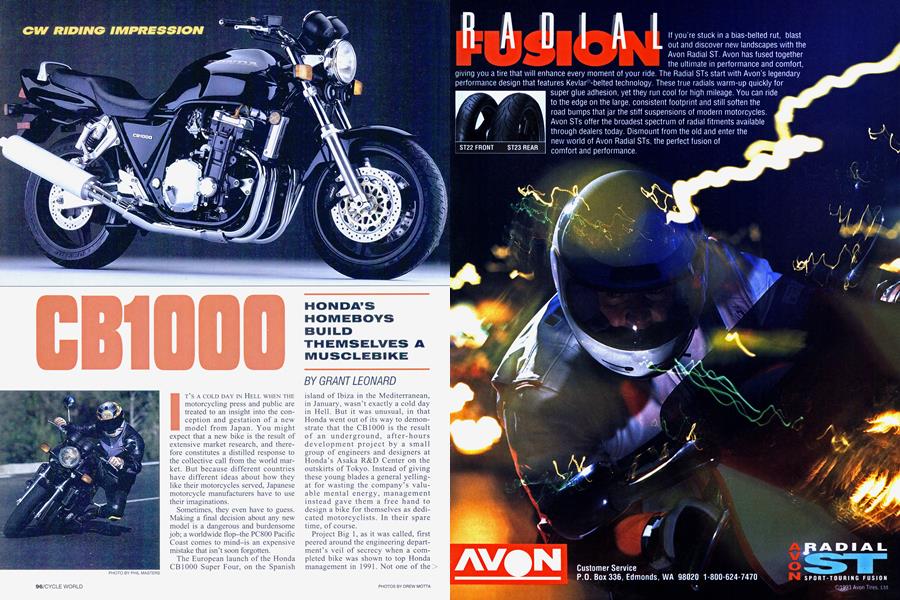

CB1000

CW RIDING IMPRESSION

HONDA’S HOMEBOYS BUILD THEMSELVES A MUSCLEBIKE

GRANT LEONARD

IT’S A COLD DAY IN HELL WHEN THE motorcycling press and public are treated to an insight into the conception and gestation of a new model from Japan. You might expect that a new bike is the result of extensive market research, and therefore constitutes a distilled response to the collective call from the world market. But because different countries have different ideas about how they like their motorcycles served, Japanese motorcycle manufacturers have to use their imaginations.

Sometimes, they even have to guess. Making a final decision about any new model is a dangerous and burdensome job; a worldwide flop-the PC800 Pacific Coast comes to mind-is an expensive mistake that isn’t soon forgotten.

The European launch of the Honda CB1000 Super Four, on the Spanish island of Ibiza in the Mediterranean, in January, wasn’t exactly a cold day in Hell. But it was unusual, in that Honda went out of its way to demonstrate that the CB1000 is the result of an underground, after-hours development project by a small group of engineers and designers at Honda’s Asaka R&D Center on the outskirts of Tokyo. Instead of giving these young blades a general yellingat for wasting the company’s valuable mental energy, management instead gave them a free hand to design a bike for themselves as dedicated motorcyclists. In their spare time, of course.

Project Big 1, as it was called, first peered around the engineering department’s veil of secrecy when a completed bike was shown to top Honda management in 1991. Not one of the design team members subsequently felt obliged to fall on his sword, indicating that the brass liked what it saw. And why not? The CB1000 is big and heavy, but it’s very manageable nevertheless. It’s comfortable at sustained speeds up to 80 mph, it has a torque-wealthy motor, and it handles and brakes well. The CB1000 Super Four has, in other words, turned out to be a fun bike.

First in line for the wrong end of his Ginsu knife had the new bike been unacceptable was Kunitaka Hara, the design-team leader of Project Big 1. He and his co-conspirators minimized the necessity of ceremonial suicide by making their project especially attractive to the Honda big-wigs and beancounters by using many off-the-shelf components. These include a mildly retuned CBR1000F motor, a modified RC30 fork and the mother-of-allswingarms—an adaptation of the CBR900RR’s.

The rest of the bike is special to the CB1000. The frame is a tubular steel double cradle that is braced like Mike Tyson’s cell door. The tank and tail unit have touches of old and new Hondas in them-the styling result is > nostalgia with balls.

The motor, with its black, unfinned, industrial-strength look, is detuned from the CBR’s 125 horsepower to a more-gentlemanly 98 horses at 8500 rpm. This detune is accomplished by a compression ratio relaxed from the CBR’s 10.5:1 to 10:1; milder cams and revised valve timing; narrower intake and exhaust ports; and a restrictive 4-into-l exhaust system. The engine is fitted with roughly the same semi-flatslide carbs the CBR600F2 sucks on, and the programmed ignition system gives optimum spark advance at all revs by measuring throttle opening against engine speed. The bottom line to all this fiddling is that the engine’s torque peak is lowered by 2000 rpm-it now develops a claimed 64.4 foot-pounds at 6000 rpm. The resulting strong torque throughout the rev range allowed Honda to forego a sixth gear in favor of a fivespeed gearbox. Additionally, Honda replaced the CBR’s shim-and-bucket valve adjustment with screw-type adjusters, and the CBR’s counterbalancer was retained.

The chassis design is in line with the bike’s intended mission as a boulevard blaster, or as Hara-san puts it, “a big, unfaired musclebike, a bike with blood in its veins.” To help give the Big l a massive look, it was intended from the start to roll on 18-inch wheels shod with tires specially designed for the CB1000.

The result is such a user-friendly package that you can jump on and ride without having to adapt in any way. Everything is where your body expects it to be; you don’t have to look for the footrests, and the bars lean you slightly forward, with plenty of weight spread between your butt and your boots. The steering is neutral and predictable, the brakes have good feel and aren’t grabby, and the motor is mostly smooth and tractable. The CB1000 allows you to rip, or to just get on and enjoy the scenery.

But it isn’t all roses. So seamless is the bike that its more obvious faults stand out in bold relief. Besides some nasty 5000-rpm vibration that sneaks past the counterbalancer, the Honda’s biggest problem-at least as exhibited on the press-preview bikes-is far too much slack in its transmission. As you feed the throttle on and off and on, the power reaches the rear wheel with a slap-bang-jerk, every time. It seems when Honda’s engineers removed sixth gear from the CBRIOOOF’s cases, they sufficiently botched the transmission to very nearly spoil a good bike.

Still, the bike has some great things going for it. The engine makes excellent power from zilch right up to the redline. It picks up smartly at 3000 rpm, and after 4000 rpm it’s all stomp and lunge, right up to an indicated top speed of nearly 140 mph. Mind you, the big motor really is most fun to use when you’re riding the torque, hauling out of comers on a twisty piece of road.

The CBlOOO’s maneuverability remains its biggest surprise. Despite a dry weight of about 540 pounds, the bike feels light and easy on the move. At a walking pace, you can ride it almost like an outsized trials bike, turning 180 degrees on full lock without dabbing a foot down. Getting off to push, though, reminds you it’s actually a monster.

At higher speeds, the way the CB1000 rolls easily into bends belies its bulk. Hara says this is because the engineering team positioned the engine high in the frame to move the center of gravity up, therefore making the bike easier

to tip into turns. This is somewhat at odds with the fine balance the bike has at low speed, and with the idea that a low center of gravity makes for a nice, easy handling bike. But on the other hand, the geometry of the bike works to give stability. It has a relatively long wheelbase at 60.6 inches, and “touring” steering geometry (27 degrees rake, 4.3 inches of trail). The wide, flat handlebar plays a useful leverage role, as does the roomy riding position, which allows you to easily shift your body weight. It’s a good compromise. The steering is just on the slow side of neutral-tight turns require some heave on the handlebar-but for the most part, the big CB will stay on your side of the road without undue effort.

There’s little doubt the CB1000 could tackle a race track and lose little of its on-road composure. The fork works well over bumps at all speeds and under hard braking, and the shocks, adjustable only for preload, aren’t just retro-fashion accessories. In fact, Hara insists there is absolutely no reduction in performance using two shocks rather than a more modem single-shock system. The introduction to the bike did not provide an environment to test this theory, but the CBlOOO’s suspension coped well at all speeds around the mixed road surfaces of Ibiza.

In the end, the CB 1000 is simply what that intrepid band of Japanese designers set out to produce for themselves: a redblooded musclebike with minimal trimming and a glut of visceral appeal. It’s also a fascinating insight into what Japanese motorcycle designers do when they get home from work. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontGreen Machines

April 1993 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsYou Ain't Goin' Nowhere

April 1993 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCSpring To Action

April 1993 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1993 -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha To Go Standard?

April 1993 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupBimota Presses On With Gp Streetbike

April 1993 By Alan Cathcart