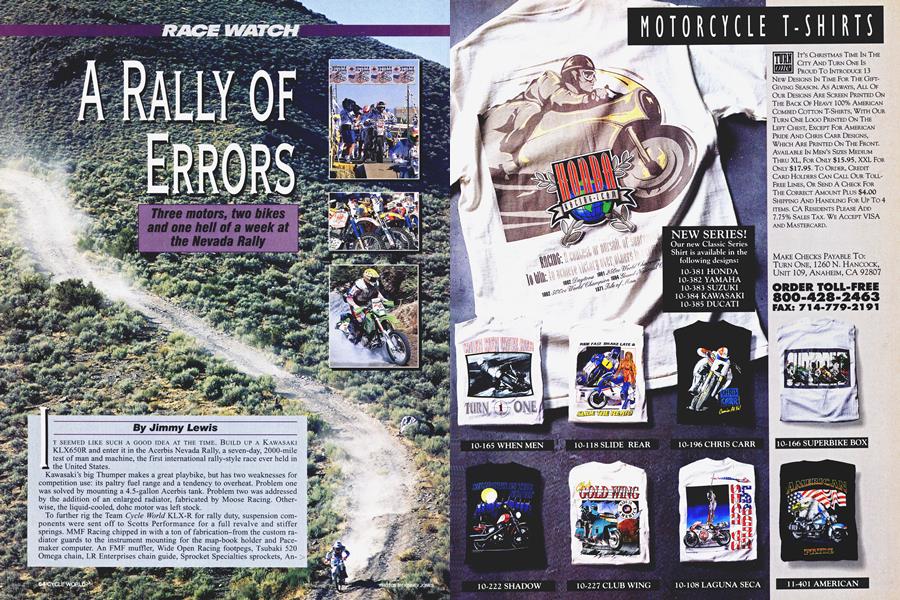

A RALLY OF ERRORS

RACE WATCH

Three motors, tow bikes and one hell of a week at the Nevada Rally

Jimmy Lewis

IT SEEMED LIKE SUCH A GOOD IDEA AT THE TIME. BUILD UP A KAWASAKI KLX650R and enter it in the Acerbis Nevada Rally, a seven-day, 2000-mile test of man and machine, the first international rally-style race ever held in Á the United States.

Kawasaki’s big Thumper makes a great playbike, but has two weaknesses for competition use: its paltry fuel range and a tendency to overheat. Problem one was solved by mounting a 4.5-gallon Acerbis tank. Problem two was addressed by the addition of an enlarged radiator, fabricated by Moose Racing. Otherwise, the liquid-cooled, dohc motor was left stock.

To further rig the Team Cycle World KLX-R for rally duty, suspension components were sent off to Scotts Performance for a full revalve and stiffer springs. MMF Racing chipped in with a ton of fabrication-from the custom radiator guards to the instrument mounting for the map-book holder and Pacemaker computer. An FMF muffler, Wide Open Racing footpegs, Tsubaki 520 Omega chain, LR Enterprises chain guide, Sprocket Specialties sprockets, Answer Pro-Taper handlebars, Ceet Dynotec seat and a K&N crankcasebreather filter completed the mods.

Based on the theory that you have to know and love people before you can abuse them, I drafted my dad and my girlfriend, Heather, as pit crew. Headed for the start in Las Vegas, our box van was packed with a spare bike, a spare motor, seven sets of wheels shod with Metzeier Unicross five-plys, Nevada maps, pit maps, quick-fill dump cans and 125 gallons of F&L race gas.

As it turned out, building the bike and organizing the pits was easy. Keeping the bike running proved almost impossible.

I rode to a less than spectacular 23rd in the prologue, a short special test to determine starting positions held in the parking lot of the Excalibur Hotel, the event’s main sponsor. Winning time was logged by past American ISDE gold medalist Charles Halcomb. Right behind Halcomb was Honda’s Baja rider Dan Ashcraft, followed by a host of European rally regulars.

The Nevada Rally was made up of “transports” and special tests. The

transports were sections of asphalt or graded dirt road that led to the special-test sections. Scoring was figured by the total elapsed time of a rider’s special tests, plus any penalty

time assessed for taking too long in the transport sections.

On the first special test, riders started at one-minute intervals, disappearing into the 105-degree heat of the >

dusty Mojave Desert, heading down a powerline road towards the Nevada border town of Mesquite, the destination for the first day. As determined by the prologue time, I would take off 23rd, 22 minutes behind the leader.

The mighty KLX was working like a dream, putting out plenty of power and handling perfectly. My Moose course computer/odometer was spoton, making it a snap to hit all of the turns listed in the road book. It was only a couple of miles before I started passing riders.

Then I reached the 33.12-mile spot.

I remember it well because at that point the now-not-so-mighty KLX backfired its last sign of life. I quickly downshifted and tried to bump-start it, but to no avail, rolling to a stop amid the most horrendous smell. I thought the air filter had caught fire, and dove into my fanny pack for the 8mm sock>

et to remove the seat. No evidence of flames. Kicking the bike through only brought more confusion as everything felt mechanically sound. Removing the sparkplug revealed the horrible truth: 30 miles and less than an hour into the rally, I had no ignition.

I pushed the bike to a railroad overpass to get out of the heat and managed to flag down a lagging Japanese rider for a tow to the next gas stop, where the dead KLX was loaded onto a truck. That night, we determined that the motor had overheated enough to melt the epoxy right off the ignition, causing the failure. Passing up a night’s sleep, my dad and a few friends from other support crews switched motors so I could start the next day.

At 6 a.m., the Kawasaki was finally buttoned up as event leader Dan Ashcraft gunned away from the start line. I was to leave almost last, having incurred a four-hour penalty for

not finishing the first day. Arriving in the mining town of Ely for the night, it was clear my problems were far from over. Inspection and another late night revealed that the clutch was slipping just enough to build up a near-fatal amount of heat in the motor. We changed oil and began looking for a solution.

The third day, I started in 14th position thanks to my previous day’s score, but I was still way back in overall results. The dust was becoming brutal now, as very dry conditions and no wind fueled the situation. I was only 20 miles into the day when the KLX once again hinted at death by making ominous sounds. I backed off the throttle and nursed the bike for the remaining 320 miles into Elko, Nevada.

There, we put some very stiff clutch springs out of a KTM into the 650R, nearly locking the clutch solid in hopes of being able to finish without cooking the motor. But apparently the engine had already had enough abuse and while idling after a highspeed test run, it started coughing and

died from a blown head gasket.

Well, great. Now what to do? Dad, Heather and I were already in serious sleep-deprivation mode, friends from other crews had their own problems, and the thought of pulling another all-nighter in order to transplant the engine from our spare KLX into the racebike didn’t hold much allure. Call it cheating-I prefer to think of it as creative interpretation of the rulesbut after weighing the options, we bolted the fuel tank, seat and suspension from the rally bike onto the stocker and went to sleep. We were so far down in the standings that I was just riding to finish anyway.

Rolling out of bed at 4:30 a.m. was now becoming routine. As the day unfolded, at least the motor seemed to be

holding together, and things in general were looking up. Then I was roosting through the second test of the day and came across an accident involving a truck and one of the rally racers. Tragedy had struck, with Australian racer Geoff Eldridge, 43, fatally injured in the incident. Although the event’s medical crew was on hand almost immediately, nothing could be done. Event promoter Franco Acerbis, a close friend of Eldridge’s, spoke that night at a somber riders’ meeting, saying that he believed-as did most of

the competitors-that the rally should go on in memory of Eldridge.

After a scheduled day of rest and surprisingly only minor bike maintenance for me, Day Five made its way towards, Tonopah, Nevada, supposedly the UFO-sighting capitol of the world. I started off 14th for the day and at the end of a tricky special test, only three riders were in front of me. French rider Alain Olivier took the lead on this day. He was entered on the only other KLX650R in the event. How could he have such a smooth race while I was having mechanical complications out the wazoo?

“Special clutch,” he replied, “I have many problems in African rallies ’til we get special clutch. Now we have all stock except for clutch.”

The final day was to be a showdown >

between Olivier and Ashcraft, as only 3 minutes separated these riders after five days and nearly 2000 miles of racing. Olivier was first off into the desert, headed south to the finish in Las Vegas. Ashcraft was second off the line by 1 minute, and needed to pass Olivier and put 2 minutes-plus on the Frenchman to take the win. I was fourth away, happy to start ahead of the pack for once and away from the worst of the dust. Twenty miles into the ride, I saw Ashcraft walking backwards on the course, his Honda dead of ignition failure, his hopes of a win doomed. Olivier needed only to finish to take the overall victory. My second-overall, fifth-on-time finish for the last leg moved me to 28th place in the overall standings out of 48 finishers. But my troubles weren’t quite over. During the final transport, with the finish banner in sight, motor number three expired, and I had to bag a tow across the line-a fitting end to my rally of woe.

But that doesn’t mean I won’t be back next year. All I’ve got to do is get that fast French guy to let me in on his clutch secret. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontWayne Rainey, World Champ

December 1993 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsTriumph Motorcycles In America

December 1993 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCAnother 100 Years?

December 1993 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1993 -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki For 1994: Out With the Old, In With the New

December 1993 By Don Canet -

Roundup

RoundupAnother Excellent Oddball From Ktm

December 1993 By Jimmy Lewis