SOLITARY BEEMER

TODAY’S BMWs ARE AT TECHNOLOGY’S CUTTING EDGE. IT WASN’T ALWAYS THAT WAY.

ANYONE WISHING TO chronicle the pursuit of excellence might look no farther for a subject than Bayerische Motoren Werke of Munich, Germany.

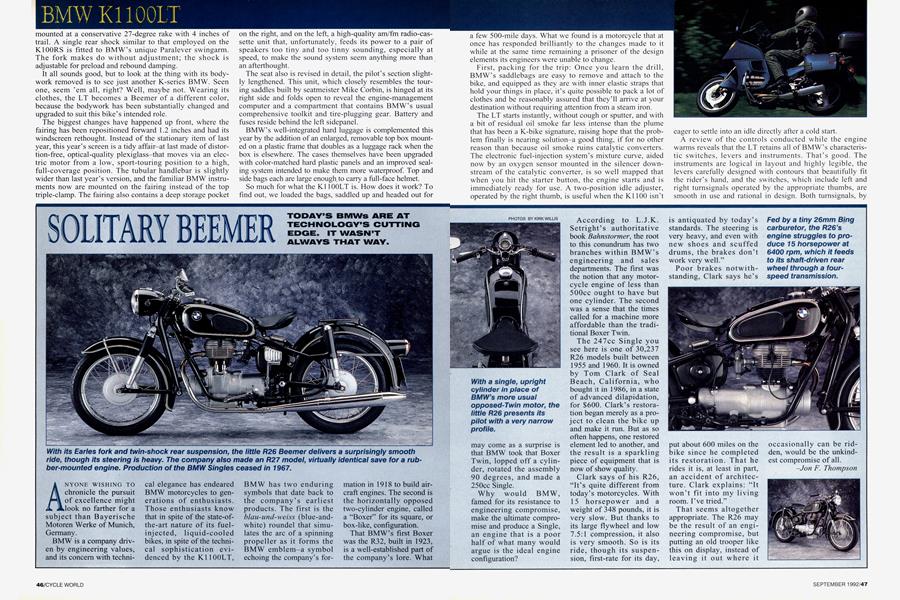

BMW is a company driven by engineering values, and its concern with technical elegance has endeared BMW motorcycles to generations of enthusiasts. Those enthusiasts know that in spite of the state-of-the-art nature of its fuel-injected, liquid-cooled bikes, in spite of the technical sophistication evidenced by the K1100LT, BMW has two enduring symbols that date back to the company’s earliest products. The first is the blau-und-weiss (blue-andwhite) roundel that simulates the arc of a spinning propeller as it forms the BMW emblem-a symbol echoing the company’s formation in 1918 to build aircraft engines. The second is the horizontally opposed two-cylinder engine, called a “Boxer” for its square, or box-like, configuration.

That BMW’s first Boxer was the R32, built in 1923, is a well-established part of the company’s lore. What may come as a surprise is that BMW took that Boxer Twin, lopped off a cylinder, rotated the assembly 90 degrees, and made a 250cc Single.

Why would BMW, famed for its resistance to engineering compromise, make the ultimate compromise and produce a Single, an engine that is a poor half of what many would argue is the ideal engine configuration?

According to L.J.K. Setright’s authoritative book Bahnstormer, the root to this conundrum has two branches within BMW’s engineering and sales departments. The first was the notion that any motorcycle engine of less than 500cc ought to have but one cylinder. The second was a sense that the times called for a machine more affordable than the traditional Boxer Twin.

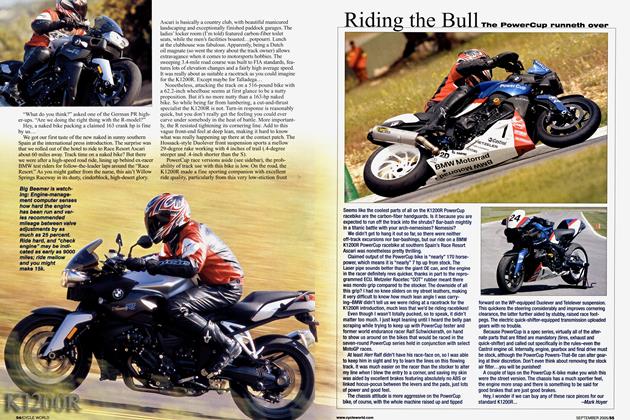

The 247cc Single you see here is one of 30,237 R26 models built between 1955 and 1960. It is owned by Tom Clark of Seal Beach, California, who bought it in 1986, in a state of advanced dilapidation, for $600. Clark’s restoration began merely as a project to clean the bike up and make it run. But as so often happens, one restored element led to another, and the result is a sparkling piece of equipment that is now of show quality.

Clark says of his R26, “It’s quite different from today’s motorcycles. With 15 horsepower and a weight of 348 pounds, it is very slow. But thanks to its large flywheel and low 7.5:1 compression, it also is very smooth. So is its ride, though its suspension, first-rate for its day, is antiquated by today’s standards. The steering is very heavy, and even with new shoes and scuffed drums, the brakes don’t work very well.”

Poor brakes notwithstanding, Clark says he’s put about 600 miles on the bike since he completed its restoration. That he rides it is, at least in part, an accident of architecture. Clark explains: “It won’t fit into my living room. I’ve tried.”

That seems altogether appropriate. The R26 may be the result of an engineering compromise, but putting an old trooper like this on display, instead of leaving it out where it occasionally can be ridden, would be the unkindest compromise of all.

-Jon F. Thompson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAn American Racer

September 1992 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsElectra-Glide

September 1992 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCOily Harry

September 1992 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1992 -

Roundup

RoundupNorton's Future Assured, Maybe

September 1992 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupShoei Reorganizes

September 1992 By Yasushi Ichikawa