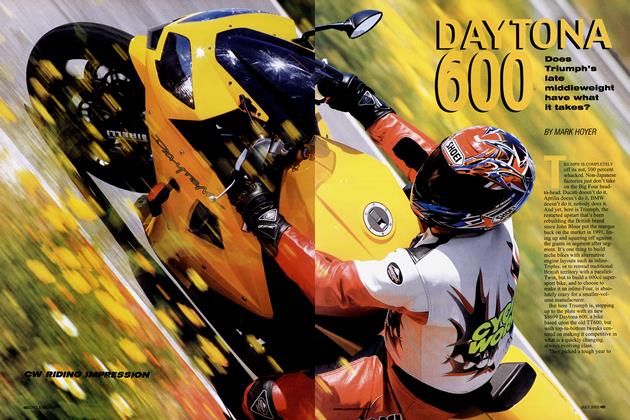

DAYTONA 1000

CW RIDING IMPRESSION

Moto Guzzi flies again

ALAN CATHCART

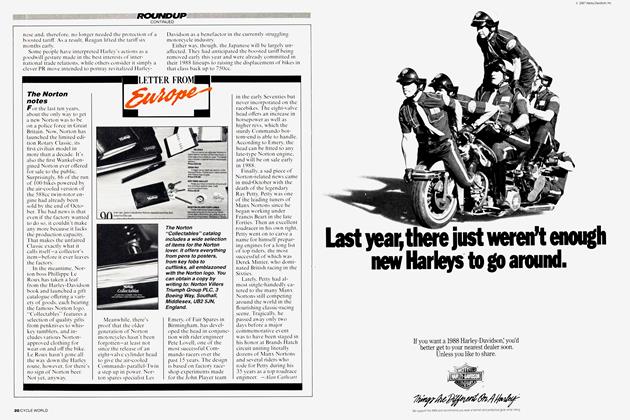

EVEN BY NOTORIOUSLY STRUNG-OUT ITALIAN STANdards, the development cycle of the fuel-injected Moto Guzzi Daytona 1000 has been a long one. Guzzi engineer Umberto Todero actually designed the eight-valve motor, with its belt-driven, not-quite-overhead camshafts, in 1985. The result didn’t appear in public until 1988, when it scored a remarkable third place in the Daytona Pro-Twins race, fitted in an innovative steel backbone chassis built by racing dentist Dr. John Wittner.

By then, Wittner was working full-time for the Italian factory with the eventual aim of developing the bike into a fuel-injected, shaft-drive answer to Ducati’s own new eightvalve desmo roadster. But when the prototype Guzzi Daytona 1000 debuted at the 1989 Milan Show, it was still wearing carbs. Weber/Marelli EFI was quoted as an option, but by the time the completely restyled and slightly re-engineered production version of the bike surfaced at Milan last November, fuel injection had become the only choice.

And now, six months later, the machine Guzzi boss Alejandro de Tomaso says will represent the basis of a complete re-launch of the Guzzi line is poised to go into production.

To all those Guzzisti who have been pestering dealers for deliveries of this new model, all I can say after a preview ride on one of the first bikes off the production line is that this bike is worth the wait. My ride took place at the Vallelunga race circuit north of Rome, and was followed by a swift blast up the roads nearby. And my assessment is that the factory’s main problem will be building enough bikes to satisfy the demand. The first production batch will number just 500 machines, which will barely dent the outstanding orders for the model, already numbering nearly 700 units. That Daytona 1000 deliveries are likely to be strictly rationed is all the more remarkable in view of the bike’s steep retail price, 20,484,200 lira in Italy, the equivalent of about $17,000.

Those successful in elbowing their way to the front of the line are unlikely to be disappointed by their purchase. For while the Daytona is not yet perfect, it encapsulates traditional Italian brio and brings Moto Guzzi engineering up to pace. The Guzzi pushrod Twin built in recent years has displayed about as much high technology as a VW Beetle, but the Daytona turns a new page, and does so without sacrificing the traditional, esoteric appeal associated with the marque.

Traditionalists will be pleased that the Daytona is still an air-cooled, transverse V-Twin with shaft final drive, and that its distinctive bodywork is a half-faired tribute to the café racers of the ’70s, leaving the engine exposed for all to see.

But don’t get the idea this is an Italian retro-bike. What we have here is Guzzi’s calling card for the 21st Century, equipped with the sort of electronic engine-management system that only the NR750 Honda, among Japanese bikes, can equal. It is able to deliver vivid performance (claimed top speed is over 150 mph) with a light touch and ease of control, with handling better than any Guzzi V-Twin ever made. The Daytona is definitely a watershed model.

Guzzi has been busy in the two years since the first appearance of the prototype Daytona. You discover this as soon as you sit on the bike. The Daytona is comfy for a six-footer, with footrests located quite high up, but without forcing the trademark knees-out Guzzi posture, thanks to the fact that the seat is also quite high-set. This throws a fair bit of body weight onto the handlebars, but the riding position isn’t extreme, racereplica-style. With a 58.3-inch wheelbase, the Guzzi is a far rangier bike than it appears to be, and the factory plans to offer a dual seat option, with bolt-on footrests and space for a passenger obtained by a pad atop the seat hump.

Should this option

materialize, Guzzi will have to persuade Koni, suppliers of the shock-fitted cantilever-style without any linkage to the chrome-moly steel box-section swingarm-to offer a far more convenient means of adjusting preload than is presently available. The shock is adjustable for preload, compression and rebound damping, but only by removing the seat to gain access. Normally, this might not be so inconvenient, were it not for the fact that the rear suspension has apparently been set up for flyweights, so the spring requires a lot of preload to eliminate bottoming in dips and in comers taken at speed. The Marzocchi MIR fork is likewise too soft on its standard settings, making my first couple of laps at Vallelunga somewhat frightening, until I stopped to do something about it. Each fork leg has a three-position clickswitch set into the top, the left controlling compression damping, the right rebound. Cranking these up to medium setting on the left and hardest on the right transformed the bike and it started handling well. Wittner says the factory recognizes that a stiffer rear spring is needed for most markets outside Italy and Japan, so when the bike goes on sale, customers will be able to specify a spring rate appropriate to their body weight.

Getting the rear spring and shock rates right is critical, says Wittner, because the bike’s rear suspension system doesn’t really eliminate torque reaction from the shaft drive. Rather, it transfers those forces elsewhere. This means that unless you have the preload set so that the swingarm has a proper degree of droop with the rider in place, cracking the throttle open exiting a turn serves to amplify the inherent squat, further compressing the shock and dropping the rear end. This can quite dramatically use up the otherwise adequate ground clearance. So, page one of the Daytona owner’s manual will emphasize the importance of adjusting the rear shock setting to suit the rider’s weight.

Apart from this, though, the Daytona’s rectangular chrome-moly steel backbone chassis, with the underslung engine used as a stressed member and sandwiched by the distinctive twin cast-aluminum swingarm pivots, handles superbly. You have a hard time convincing yourself this is really a Moto Guzzi, not only because the steering is so much quicker and more positive than anything Moto Guzzi has ever produced, but also because of the near-total absence of any torque reaction once you’re on the move, either from the shaft final drive or from the longitudinal crank. Helping here is a steel flywheel drilled to save a whopping 6.4 pounds compared to the one used on the pushrod engine.

The only time you get a reminder what sort of bike you’re riding is when you stuff it into a lower gear coming up to a turn, using engine braking to skim off speed. That’s when the Daytona briefly shakes from side to side. But in slow turns and high-speed sweepers alike, the 1000 is ultra-stable, even if you back off the throttle and get on it again in mid-turn. It’s a forgiving motorcycle.

A servatively long key factor gearbox in long the casing. bike’s wheelbase, Todero stability necessitated has is drawn surely up that by a consixthe speed gearbox nearly 2 inches shorter than the one used presently, but there’s no budget to make it, so the Daytona not only has to live with the longer casing, it also has a five-speed transmission. Shifting is precise, the only problem being that you have to use all the lever’s considerable travel to be sure of not getting a false neutral, especially in the top two ratios.

The Daytona goes from side to side amazingly easily by Guzzi standards. Steering geometry is the same as on the original prototype, with a 26-degree head angle and 4 inches of trail. While this is conservative by contemporary sportbike standards, the Daytona feels very agile, and shows an excellent compromise between stability and nimbleness, even under heavy braking.

Braking feel could be better. At a claimed 452 pounds dry, this is by no means a heavy bike. But there isn’t quite the bite from the twin 11.8-inch front Brembo discs and four-piston calipers that I was expecting. There are two reasons for this, I think. The first is pad choice, and the second is the use of steel discs, rather than cast-iron ones.

If the Daytona’s handling is quite unlike that of any other street Guzzi, the bike’s eight-valve engine is equally different from its pushrod ancestors in feel and power delivery. And it is quite different from the engine used in the prototype Daytona I rode almost three years ago. That was an old-fashioned Guzzi tractor motor, with acres of midrange torque, heavy throttle springs and lots of musical accompaniment from the engine and plain-Jane, black-painted exhausts. The production bike’s motor is immeasurably more refined.

Though originally based on a modified Le Mans engine, the Daytona’s 992cc motor (90 x 78mm bore and stroke) is effectively an all-new design whose crankcases and crankshaft are the only parts shared with the pushrod version. There’s less midrange power than found in the prototype, with a flat spot in the delivery around 4000 rpm. This means you need to keep revs above 4500 rpm to stay in the powerband. Over 5000 rpm, things get much more exciting, with a very flat torque curve that sees maximum torque of 70 foot-pounds delivered at 5800 rpm and maintained all the way to 7200 rpm. It falls off very little above that, and the engine runs very strongly up to the 8100-rpm rev-limiter cutoff. Horsepower is a claimed 95 at 8000 rpm.

The excellent gear bike to help feels acceleration, you slightly get off undergeared, thanks to the a very mark, but and the low four result bottom upper is ratios that help you stay in the engine’s 3000-rpmwide sweet spot.

So you see, patience is indeed a virtue. Guzzi has taken its time to develop the Daytona, and as a result has produced, finally, a bike that vaults the company into the modern era. The Daytona 1000 in its present form is a worthy counterpart to Ducati’s 851, and will surely find a number of enthusiastic buyers. Guzzi must realize that the market exists for an uprated version of the bike, something equivalent to Ducati’s 888.

You won’t get anyone in the company to confirm plans for such a bike, except the boss, who supplied only a veiled hint: “The reason we took so long to get the Daytona into production was because we knew at all costs we had to get it right,” de Tomaso told me. “This is the start of a new chapter for Moto Guzzi, and our future model range will be closely based on the Daytona philosophy.”

Sounds good. Now, let’s see how high the new Guzzi flies. □