WORK IN PROGRESS

Yamaha's anti-Aprilia

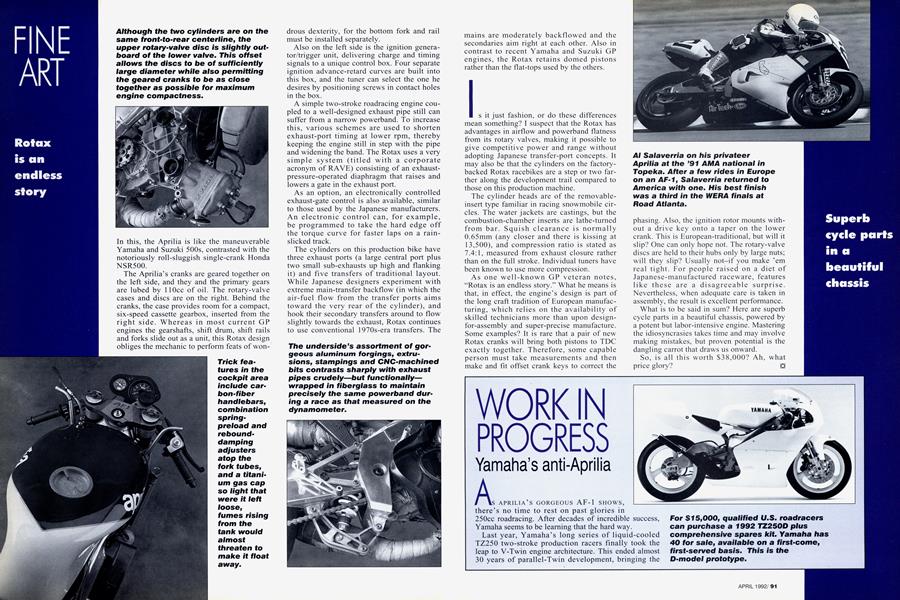

AS APRILIA'S GORGEOUS AF-1 SHOWS, there’s no time to rest on past glories in 250cc roadracing. After decades of incredible success, Yamaha seems to be learning that the hard way.

Last year, Yamaha’s long series of liquid-cooled TZ250 two-stroke production racers finally took the leap to V-Twin engine architecture. This ended almost 30 years of parallel-Twin development, bringing the TZ’s design into line with the past seven years of factory-team V-motor development.

V-Twin layout reduces vibration and engine width, and concentrates weight farther forward. A 90-degree, single-crank V-Twin achieves perfect primary balance provided the rods and pistons operate in the same plane. As they are moved out of a single plane (as they must be to provide a two-stroke with separate, sealed crankcases), a vibratory rocking couple appears, proportional to cylinder separation.

The new V-Twin’s separation, at 65mm, is far less than the old parallel-Twin’s, which was more than 100mm, and the couple is in any case canceled by a 20ounce balancer shaft, geared to the crank. The 1991 motorcycle, with its vibration thus reduced, did not suffer the extensive frame cracking that the last of the parallel-Twins did in 1990. As a further bonus, the reduced vibration permitted the rubber engine mounts of the ‘90 model to be replaced with solid mounts, allowing the engine to contribute to chassis rigidity. This, in turn, permitted a weight reduction.

To limit the expense of all these changes, the ‘91 model was implemented on the crankcase and chassis elements of a Japanese-market streetbike, but with cylinders extensively based on current 500cc developments. Instead of concentrating on power, Yamaha gave these cylinders unprecedented bottom-end punch. Early testing in 1991 revealed a complementary deficit in topend power, as compared with the 1990 A-model. Mother Nature can be stingy.

Now comes the 1992 D-model TZ, with an entirely new chassis, plus new cylinders, heads and pistons. The new chassis saves weight by replacing cast production elements with lighter sheet-metal weldments. The top of the rear damper no longer attaches to the seat frame, but terminates lower down, on a stout crossmember of the main chassis beams.

The 1991 fork appeared modern, being of trendy inverted design, but its stiction, misalignments and internals left much to be desired, motivating many users to fit Öhlins forks. The new fork includes tunable washer-stack damping elements and is expected to be better.

The new cylinders are also a departure. For the past five years, Yamaha TZ250 cylinders have had four transfer ports plus a finger (reed) port, with a single main exhaust port flanked by two boosters. The new cylinder has six transfer ports, plus a narrowed finger port, with triple exhausts as before. Increasing the number of transfers improves control over flow direction, but the additional port divider slightly reduces potential transfer area. To counter this, Yamaha has stopped running the piston-ring end gap down a wide septum between a secondary transfer and the reed port. Instead, the gap rides directly across the center of the narrowed reed port, as Rotax has safely done for over a decade.

The 1991 cylinder had strongly backflowed main transfers, as found in streetbike designs. This enhances torque at lower rpm, but hurts up high. On the 1992 cylinders, the main transfers are less backflowed than a year ago, and the flow direction of all transfers is aimed at the center of the piston. In late-fall testing in Florida, the 1992 machine was as strong as a 1991 model that had received a year of careful development.

As in 1991, the pistons have flat rather than domed crowns, but there is a difference in the 1992 item. The 1991 piston had a narrow chamfer 2-3mm wide at the top edge; in the 1992, this chamfer is widened considerably, and its angle is increased. There is some suggestion in two-stroke literature that this chamfer can improve the flow from the transfer ports when they are less than fully open-without requiring that the piston be domed. Although the same casting is used to make the piston, the 1992 item has a slightly longer skirt-piston rings like a well-stabilized piston.

The fairing of the new model is noticeably smoother

than before, and more extensive measures have been taken to deliver clean, cool air to the carburetors.

The 1991 model was a great success in U.S. racing, but a failure at GP level. An “M” kit was produced to boost its European prospects, but this, too, missed its mark. Some feel that the smallish production reed valve is the limiting factor (it is substantially smaller than, say, current Honda NSR250 reeds). More than likely, it’s because Yamaha is concentrating on its very successful 500cc GP program to the virtual exclusion of 250 development. Clapping last year’s 500 cylinders onto a production crankcase is expedient, but is no substitute for a separate and intensive 250cc development program such as Honda and Aprilia have. Even Suzuki fielded a 250 in 1991 GPs-its first in more than 20 years-and although it, too, was 500-derived, Suzuki’s program had more depth (and success) than Yamaha’s. The success of the 1992 TZ250D will therefore depend upon the speed and quality of development its users can apply to it.

See you all at the dyno . Kevin Cameron

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontUncle George's Last Ride

April 1992 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Enchanted Vagabond

April 1992 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCRocket Fuel

April 1992 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1992 -

Roundup

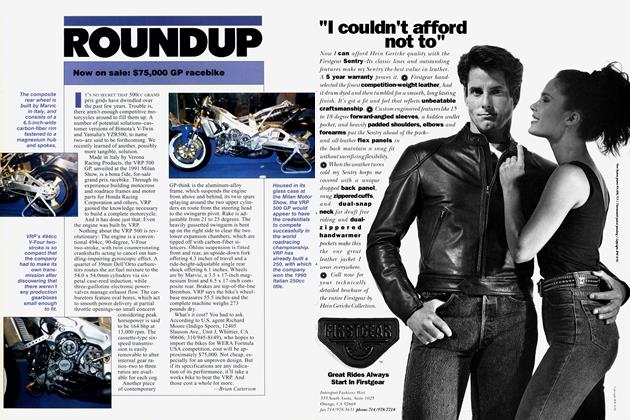

RoundupNow On Sale: $75,000 Gp Racebike

April 1992 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

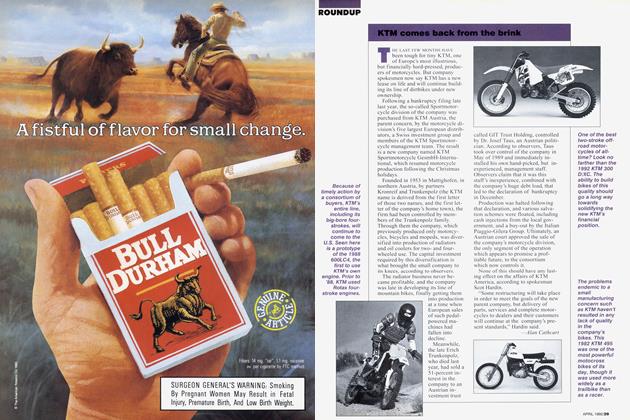

RoundupKtm Comes Back From the Brink

April 1992 By Alan Cathcart